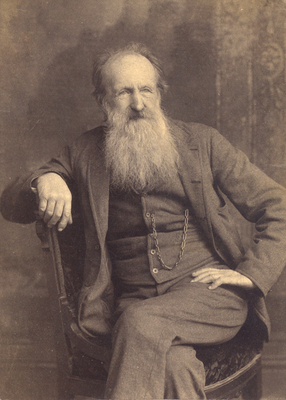

Edward Augustus Brackett

Edward (sometimes mistakenly recorded as Edwin) Augustus Brackett was the sculptor of the bust of John Brown commissioned by George L. and Mary E. Stearns. From 1841 until his death in 1908, Brackett resided in an octagonal house he built in Winchester, Massachusetts.

Brackett was a man of many talents and interests. He began his career as a sculptor in Cincinnati, moving to New York and Boston and eventually settling in Winchester, Massachusetts. He published several books of poetry and a treatise on the paranormal (titled Materialized Apparitions: If Not Beings from Another Life, What Are They). He later took an interest in horticulture and fish hatcheries, becoming the head of the Massachusetts Fish and Game Commission in 1894.

From 1841 to 1873, Brackett maintained a studio in Scollay Square in Boston, near the offices of several antislavery organizations, including that of William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper The Liberator. One of Bracket’s best-known works was Shipwrecked Mother and Child (1848–50), which now resides at the Worcester Art Museum. The piece, inspired by the drowning of renowned feminist and transcendentalist Margaret Fuller and her family off of Long Island in 1850, was controversial for its unflinching portrayal of death and nudity.

In 1859, Brackett sculpted a marble monument for the Mount Auburn Cemetery grave of Reverend Hosea Ballou I, the Universalist preacher and great-uncle of Hosea Ballou II, the first president of Tufts University. He also created busts of several notable abolitionists, including Garrison, Wendell Phillips, and Charles Sumner.

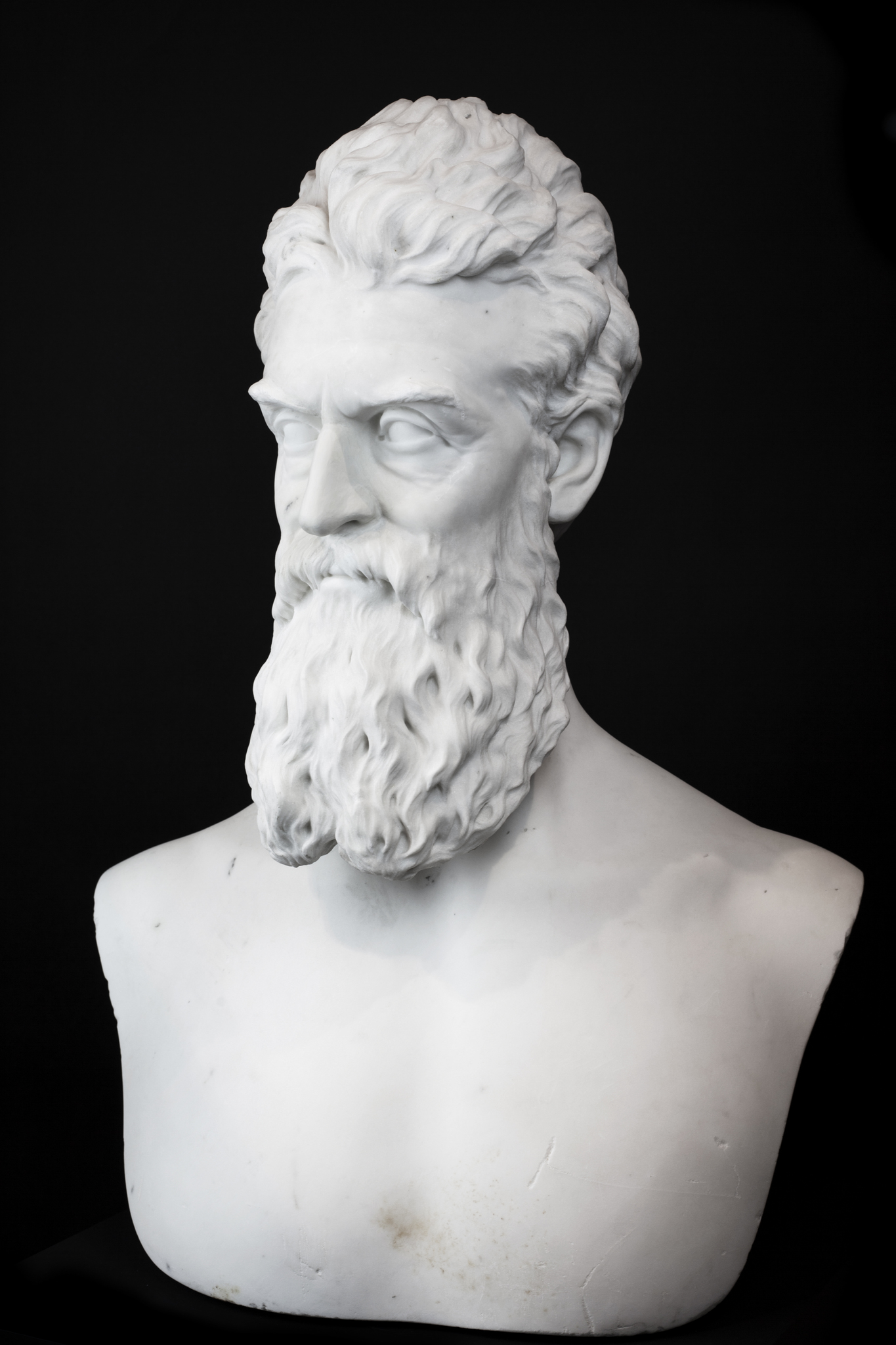

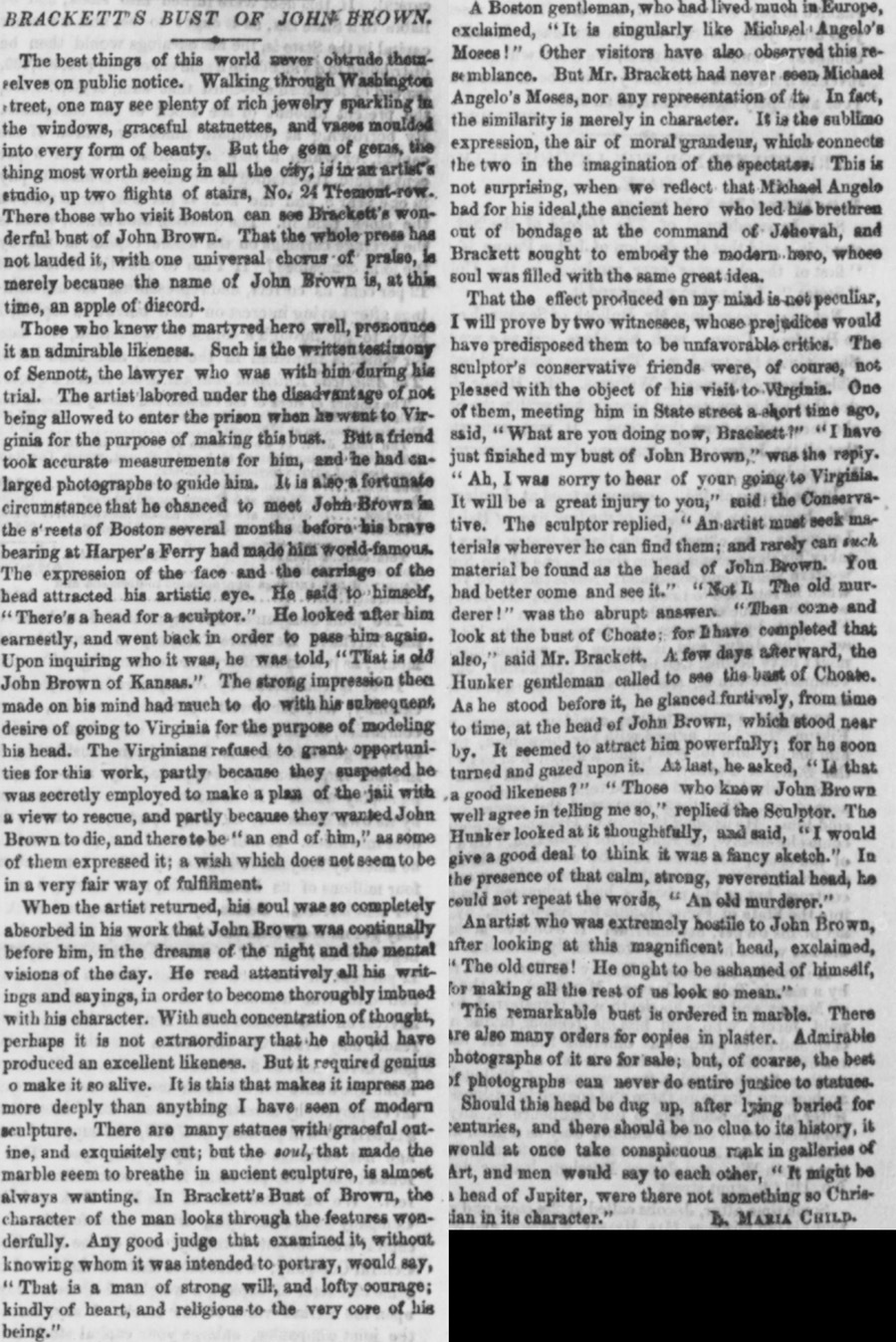

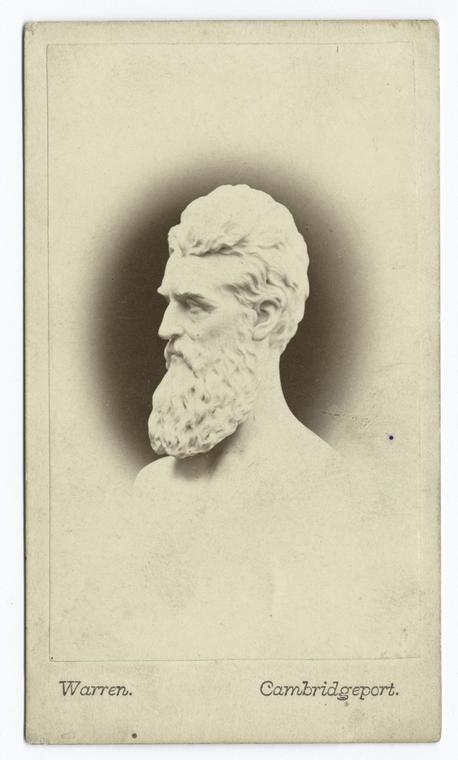

Also in 1859, Brackett traveled to Charles Town to take the measurements for a bust of John Brown (see The Bust of John Brown). Lydia Maria Child published an account of the creation of the bust the next year. Brackett himself recounted the story of the creation of the bust to writer Katherine Mayo a year before his death in 1908. His account is a tale of subterfuge and politics, well worth reproducing at the end of this page.

Around the winter of 1862, Garrison introduced Brackett to a young black and Native woman named Edmonia Lewis who wished to train as a sculptor, a profession that at the time was closed to women of color. Lewis had seen Brackett’s bust of John Brown and remarked, “A man who made a bust of John Brown must be a friend of my people.” Brackett agreed to train her. She used his sculptures as models, creating portrait medallions from the bust of John Brown to sell. The relationship between Brackett and Lewis did not end amicably and in 1865, Lewis left for Europe.

In 1869, Brackett took a job with the Massachusetts Inland Fisheries, closing his studio after he became its head in 1873. He spent the rest of his life involved with horticulture and fisheries. He died in Winchester in 1908.

Brackett’s account of creating the John Brown bust, given circa 1907:

On the morning of October 22, 1859, the Saturday following the Harpers Ferry raid, I dropped into Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe’s office in Boston, and there, with Dr. Howe, found Wendell Phillips. The two were deep in consultation over the events of the hour, and both seemed nervous—decidedly more than a little nervous. I asked if any good portrait or bust of John Brown existed. They thought not.

“I will go the Charlestown and get the necessary sketches and measurements for a bust,” said I, “if anyone will pay my expenses.”

Both men looked at me in dumb amazement, as though they thought me mad. Presently I left, having received no encouragement, and, perceiving the case, as far as they were concerned, to be hopeless. But a likelier source remained, where courage was wont to run hand in hand with sympathy. I scratched off a line to Mr. George Luther Stearns—“What do you think about taking a bust of Old Brown? Can anything be done about it?”

Next day, Sunday afternoon, Mr. Stearns drove out to my house in Winchester. “Will you really go to Charlestown?” he asked me. “If so, I can find the money for you. How much do you require?”

“I scarcely know.”

“Well, I am authorized by a lady,” Stearns went on, “to give you this,” and he placed in my hand $120 in gold coin.

I got off as quickly as possible. Reaching New York at night, next morning I set out again, and arrived in Harpers Ferry a little after dark. There I went to the hotel, an old-fashioned country tavern. I walked up to the register, by the door, and signed myself, “E. A. Brackett, Boston,” and at that time and place a man might quite as well have booked from Hell. Then I went in and sat myself down beside the wood fire in the parlor. People of all sorts and conditions came and inspected the register, then stood in the doorway and gazed at me. Some were gentle, some simple, many wore the gay uniform of one or another militia company gathered in from the country round, almost all bore arms, and to each and every man I was an object of infinite speculation. But I kept still and watched the fire burn.

At last a citizen six feet tall, weighing two hundred pounds or more, in a broad-brimmed hat, well-dressed in country fashion, entered and took a seat at my side. Prolonged silence. Then:

“You come from Boston, I hear?”

“Yes.”

“Any excitement up there?”

“None that I saw. It seems to be all down this way.”

Silence.

“What do you think of slavery?” asked the Virginian, again.

“Well, sir,” said I, “that is a large question, and calls for a long answer, and I am tired and don’t want to talk. But I’ll tell you this: I’ve travelled out West, I’ve travelled through many slave States, but I had to come back to Boston to hear slavery preached from the pulpit.”

Silence. Pause.

“I live up the hills yonder,” said the Virginian, “and we are forming little companies, here and there, to defend ourselves from these attacks on our borders. My errand in this place is to get some United States arms for our use.”

“Are you going to drill in public, out in your streets?”

“Why, yes.”

“That’s a good idea,” said I, cheerfully,” the negro is an imitative creature. He will learn from you to handle arms.”

Next morning I drove over to Charlestown, the county seat, eight miles away, where John Brown lay in jail. As I alighted at the Carter House door, to my infinite surprised the first face I saw was familiar. In the same instant, our eyes met. The young fellow took a step towards me. “For God’s sake,” he whispered, “don’t call me by name—don’t give me away!” It was House of the New York Tribune. Under cover of bona-fide credentials from a Boston pro-slavery paper, House was supplying the Tribune, as opportunity offered, with those long, picturesque, and stingingly ironical letters so bitterly resented in the South. As yet he was personally unsuspected, but the hunt was keen, and glad though he was to see a friend, House was on tenterhooks in this moment of recognition. So we made a feint of scraping acquaintance, for future use.

From the North I had brought with me letters of introduction to the United States Senator Mason, who was attending the trial, and to Mr. Andrew Hunter, the prosecuting attorney. Both received me after the manner of Southern country gentlemen, with all civility. They often walked with me in public, in the days that followed, thereby, no doubt, contributing much to the general forbearance with which I was treated in that community where excitement was so intense and where every Northerner lay naturally under suspicion as an enemy.

Yet, despite their courtesy, my two friends continued from day to day, on one plea of another, to put me off from my purpose, until I felt that they intended to defeat it; and that not by a direct denial, but by procrastination. Nor was this course without its reason. Once, when I urged upon them that to refuse an artist permission to model whom he pleased, were it the worse rascal in history, was a thing unknown, one of the two rejoined:

“Are there perhaps some people in your home who do not like you, Mr. Brackett?”

“Why, yes,” said I, “I should think myself a pretty poor sort of a man if there were not.”

Then he handed me a letter, written by a Democratic office-holder in my town of Winchester, which read, in effect: “Look out for Bracket. He is an Abolitionists spy.”

The scenes in the streets, at this time while the trials progressed, were indescribable crowded, excited, confused. During the early morning hours a constant stream of old wagons meandered in from all distances and directions through the countryside. As each arrived the driver would tie his horse to the fence with a bit of rope or “tow-strong,” adding his outfit to the long row of ramshackle vehicles and harnesses rigged together with odds and ends of parti-colored this or that. Then the new arrival would proceed to the hotel bar, drink down a glass of raw whiskey, rub his forearm across his mouth, and amble over to the court house In the afternoon, the stream ebbed.

“Comin’ in to-morrow?” one retreating figure would ask of another. “No—reckon I won’t come in again till the hangin’.”

The hotel man sided with nobody. He kept his hotel.

--

I soon found that I could not take a step unwatched. But I had known Southerners before, and I knew that frankness was my best passport. I practised it and it saved me. I announced my purpose plainly. I made no secret of my views, when asked, yet took care to define that it was business, pure and simple, not my views, that brought me. The hotelkeeper once said to me: “Mr. Brackett, you do now know our people, you should not speak so boldly. You will be mobbed before you leave, if you keep on.” But the hotelkeeper reckoned wrong.

One night, in the barroom, when, as usual, twelve or fifteen men lay around on the benches drunk, a tipsy oaf staggered my way with a great assumption of formidability, stammering. “Do you s-she m-me? A-ah-m-a Bor-rer Ruffian [Border Ruffian], thazh what ah am!”

“Don’t doubt it,” said I, pointing to the benches, “and are those your men?”

Again, the chief officer of the Harpers Ferry Arsenal, Mr. Barbour, was very friendly to Brown’s counsel, Mr. Griswold, but not at all warm to me. One day when we three were together, Mr. Barbour said to Mr. Griswold: “Would you like to go over to the arsenal, sir? I’ll show you the place where they got their brains knocked out. Would you like to go, Mr. Brackett?”

“Surely,” said I. “Any evidence of brains, hereabouts would be a God-send to me.” But never through honest and good-natured hostilities would one incur the resentment of the liberal Virginians.

At last, in despair of effecting my mission through diplomacy, I began to think of means more dark. But Capt. Avis, Brown’s kind, but invulnerable, jailor, stood in my way. To attempt anything with his knowledge and without express official permission would be worse than useless. The assistant jailor, however, presented a different front. According to a story told me later, this man had known Brown in Kansas; but whatever the cause, he was willing to connive in my scheme to the extent of his power. Nevertheless he was greatly perturbed by the fear of discovery and made me promise never to tell the tale, should anything be effected through his agency, during his life-time.

--

Finally, the opportunity arrived. The trial of Shields Green, one of Brown’s negro raiders, came on, and Capt. Avis was obliged to conduct the prisoners from the jail to the court house. In anticipation of this movement, I had prepared a conventional drawing of a head. Taking the drawing and my measuring instruments and accompanied by Mr. Griswold, I went to Brown’s cell. Mr. Griswold entered and explained to Brown my purpose.

Brown, who had no personal vanity, who felt that his work was done, and that his personality would soon cease to be of any moment whatever, was not interested. But when Griswold said, “It is at the desire of your Boston friends that Mr. Bracket comes.” The old man at once acquiesced.

Now came our consideration of the underjailer’s fears. For his sake I must be able to swear, if questioned, that I had never entered his prisoner’s cell. So I stood on the threshold, sketch in hand, almost near enough to Brown to touch him, while Griswold, with my instruments and by my minute directions, made each measurement. These I noted down in their several places on my sketch, photographing the subject on my brain the while.

The bust as you see it, is a little poetized. A man who paints a picture of a great man and puts no greatness into it, saying that he sees none, errs both in perception and in art. In this case the idealization is elusive—not to be located in any one feature. But it exists, and purposely, the more truthfully to express the character of the subject. Yet John Brown was not himself a great man, but rather a forerunner of great things. He was a blind instrument, blindly cutting the way to the death of thousands and the birth of a new age.

--

Meantime, during all these days, young House had been busily writing his reports, full of malice and laughter, for the Tribune. Still masked by his Democratic credentials, he associated Greeley with the Charlestonians and gleaned what news he wished without let or hindrance. But as the irritation aroused by his letters grew, so sharpened the search for the author. Therefore, it became increasingly necessary to observe all strategy in conveying the manuscripts to the destination. As I was packing my bag to leave, House appeared at my chamber door with a grave request to be allowed to make my toilet. Producing his copy, written on dozens of sheets of thin foolscap, he wound it around and around my calves and thighs, finally gingerly helping me into my trousers. In that costume, I reached New York, went at once to the Tribune office, and to Horace Greeley in person.

When Mr. Greeley heard that I came fresh from Charlestown, he was of course much interested, and wished to settle down for a talk.

“With much pleasure,” said I: “but I am pretty heavily clad. Will you excuse me if I undress a little in your office?”

Scarcely concealing his surprise, Mr. Greeley consented. I took off my trousers forthwith, and sheet by sheet disrobed myself of a whole week’s correspondence.

Greeley laughed aloud.

(Originally published in an article by Katherine Mayo the Evening Post, November 13, 1909, as well as in the Magazine of History, vol. 10, no. 6 (December 1909), pp. 322–328.)