John Brown and the Secret Six

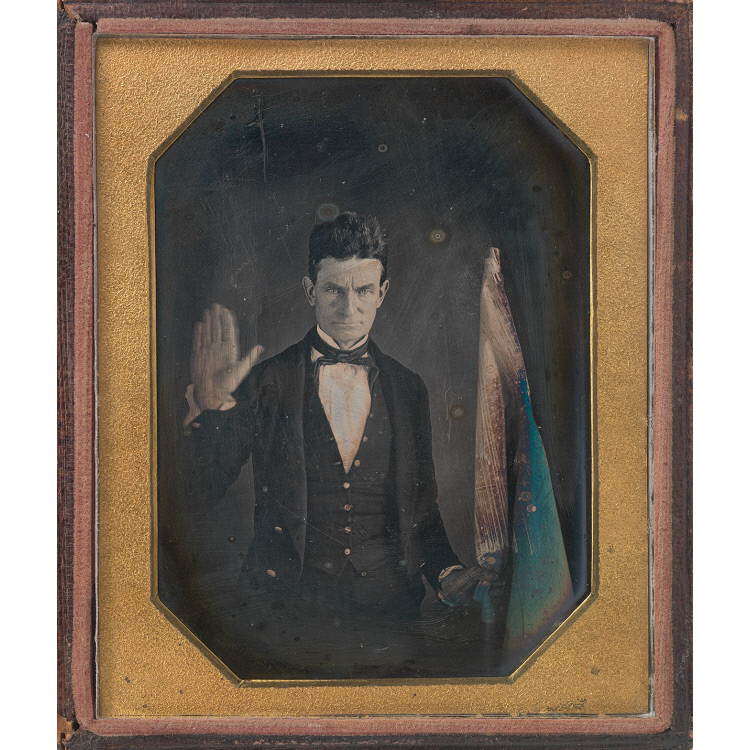

John Brown in Kansas

In 1856, Brown had resided in Kansas, participating in an ongoing series of deadly confrontations known as Bleeding Kansas. These confrontations were the result of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1864, which allowed states to choose for themselves whether they would permit slavery within their borders. The conflicts took place primarily between “Free Staters” and “Border Ruffians,” settlers sent to Kansas by antislavery activists in the North and proslavery activists in the South, respectively, as the country’s ideological war over slavery was fought by proxy on the Kansas frontier.

Brown was not only a victim of the ongoing attacks but he actively perpetuated the violence of the cause. In May 1856, Brown and fellow abolitionists killed five settlers north of Pottawatomie Creek in Franklin County, Kansas. While his motivation was reprisal for previous violence, Brown’s reputation for forceful action in the fight for abolition was firmly established. “Captain John Brown of Osawatomie,” as he was called, sought further support for increasingly ambitious attempts to rid the nation of slavery.

John Brown in Boston

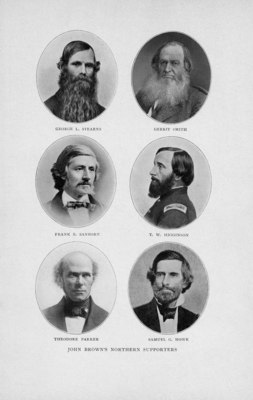

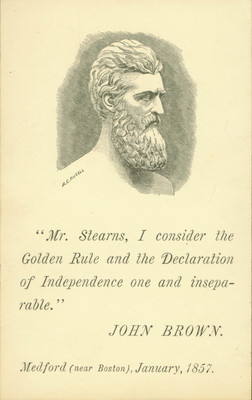

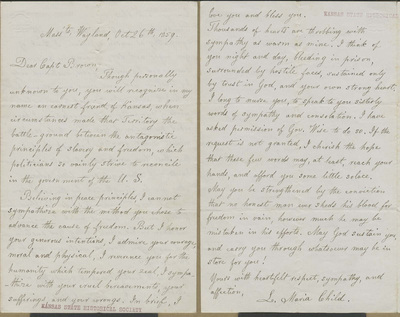

In January 1857, a young Concord schoolmaster by the name of Franklin Sanborn welcomed fellow abolitionist John Brown to Boston. The invitation changed history. Sanborn introduced the abolitionist to Medford resident George L. Stearns, with whom Sanborn worked as a member of the Massachusetts Kansas Committee, an organization that supported Free State settlers in Kansas. When, in September 1856, Stearns had offered Sanborn the position of committee secretary, their shared interest in the political landscape of Kansas formed the first ties of Boston’s “Secret Six,” a group of abolitionists composed of Stearns, Sanborn, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Samuel Gridley Howe, Theodore Parker, and Gerrit Smith.

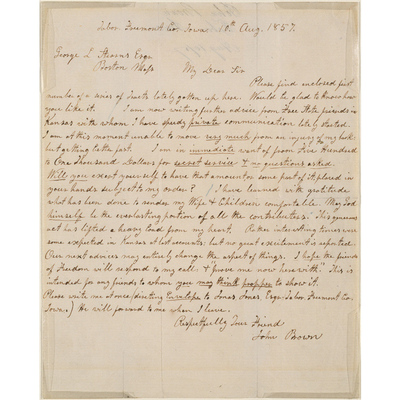

Brown arrived in Boston to gather funds for the continuation of his fight against slavery. His travels had taken him through New York and New England and, as a result, garnered the attention and appreciation of many abolitionists in the North—noted black abolitionist Frederick Douglass once said Brown was “in sympathy a black man.”

A few days after meeting Brown, Stearns invited the abolitionist to his mansion in Medford. At dinner, the Stearns family became aware of Brown’s grim passion. Stearns appreciated Brown’s willingness to act, in stark contrast to the often-ineffective talk of antislavery politicians who preached antislavery but failed to take action. It also provided the humble and reserved businessman with an outlet for his strong beliefs about equality and freedom.

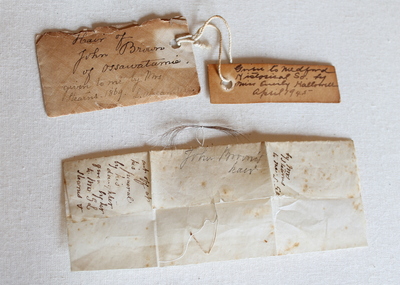

Stearns’s wife, Mary, was even more taken with Brown, later waking George in the middle of the night to insist he sell the estate to fund Brown. Stearns convinced her that they could raise funds in other ways. Mary recalled, “Both of these men were of the martyr type. No thought or consideration for themselves, for history, or the estimation of others, ever entered into their calculations. It was the service of Truth and Right which brought them together, and in that service they were ready to die.” Even the Stearnses’ oldest son, Henry, just 11 years old at the time, was so taken by Brown that he donated his boyhood savings to the man, asking in exchange to know more about Brown’s childhood. Brown later acquiesced with a letter describing his own childhood, which reveals why he became an abolitionist.

Harper's Ferry

In the early summer of 1859, John Brown returned to Boston to discuss support and gather advice from the members of the Secret Six, who agreed to finance his operations without total disclosure of his plans or intentions. Stearns and his committee provided Brown with rifles and pikes, primarily funded by Stearns, and they awaited the moment of Brown’s next attack. Before departing Boston on June 3, 1859, Brown gifted Stearns his Bowie knife—taken from a Border Ruffian in Kansas—and told him, “I am going on a dangerous errand and we may never see each other again.”

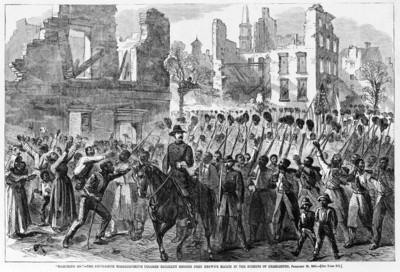

On October 16, 1859, Brown, with the assistance of only 21 men, led an attack on the Harpers Ferry Armory. He intended to seize the armory’s supplies—nearly 10,000 muskets and rifles—with which he would arm local slaves and ignite a larger rebellion that would eventually lead to the fall of slavery in the United States.

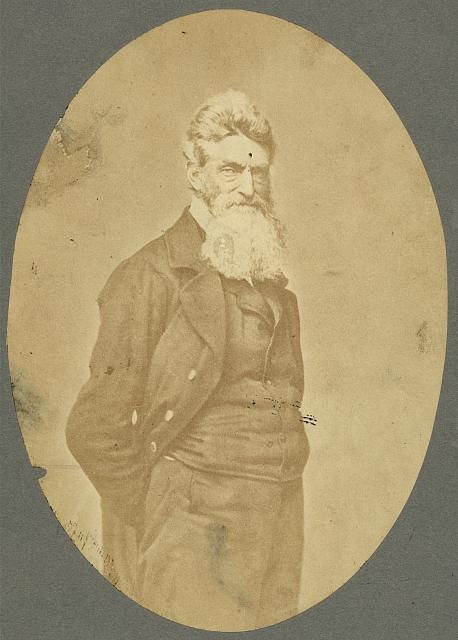

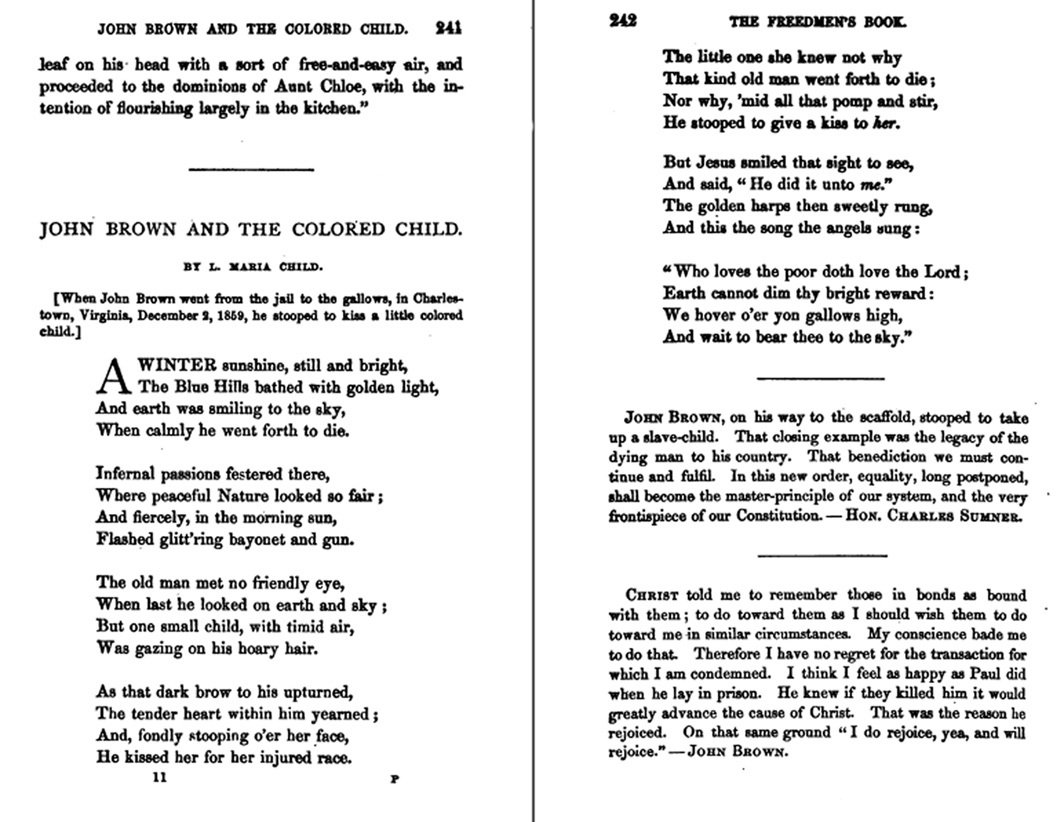

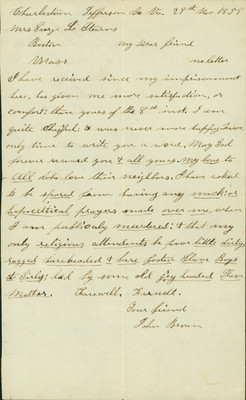

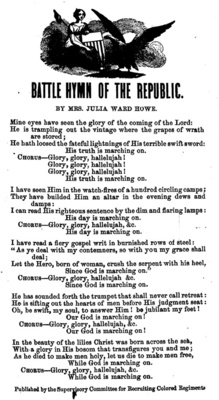

The raid failed miserably and the raiders were either killed or captured. Brown himself was badly injured and taken to Charles Town for an expedited trial that on November 2, 1859 ended in a guilty verdict. He was executed by hanging on December 2 of that year. On the way to the gallows, he was said to have leaned down to kiss the head of a black woman's baby being held up to him.

While the raid itself may have failed in its apparent objectives, the forceful campaign attracted national—and even international—attention. At first the public reaction was harshly critical. William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, one of the most important antislavery newspapers in the country, considered the violent raid to be “misguided, wild, and apparently insane.” Writing to her niece Mary Stearns, Medford native poet and reformer Lydia Maria Child remarked, “I honor Brown’s motives, but he made a great mistake. The effects may be favorable to freedom in the long run; but it is impossible to foresee the consequences.” The identities of the Secret Six were revealed and most of them fled. George L. Stearns and Samuel Gridley Howe escaped to Canada, where Stearns made a somber visit to Niagara Falls on the day of Brown’s execution.

The Legend of John Brown

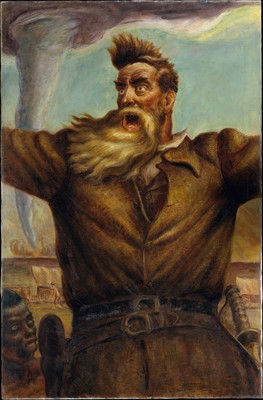

Brown’s stoic acceptance of his fate cemented his status as a martyr and turned public criticism into adulation in the North. The Boston Daily Advertiser proclaimed, “His act may stand as a symbolical expression of the intense hatred of slavery entertained by a man of integrity and courage, and so may work out good in the ultimate dispensation of Providence.” Stearns, who when questioned by the Senate Select Committee had said he would have disapproved of Brown’s plans had he known of them, later wrote, “But I have since changed my opinion; I believe John Brown to be the representative man of this Century, as Washington was of the last—the Harpers Ferry affair, and the capacity shown by the Italians for self-government, the great events of this age. One will free Europe and the other America.” In 1863, while recruiting black troops, he proclaimed, “I consider it the proudest act of my life that I gave good old John Brown every pike and rifle he carried to Harpers Ferry.”

Stearns praised Brown and many others viewed his death as something sacred. When word of Brown’s pending execution reached Ralph Waldo Emerson, the transcendentalist declared, “He will make the gallows holy as the cross.” As the frontispiece of his 1861 publication, John Brown par Victor Hugo, the French writer Victor Hugo composed a sketch of Brown hanging upon the gallows, his lone form nearly a silhouette. From behind Brown emerges a ray of light that textures the clouds and illuminates the indistinct figure. The expressiveness of the rendering is furthered through an inscription at the top of the print; Pro Christo sicut Christus (For Christ Just as Christ) equates the body of Brown on the gallows with the crucified body of Christ.

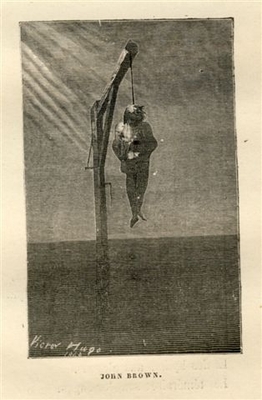

Harriet Tubman spoke of Brown in a similar tone in 1864 when, looking upon a bust of John Brown for the first time, she stated, “It was not John Brown that died at Charles Town. It was Christ—it was the savior of our people.” Her words were echoed in spirit by Julia Ward Howe of Medford, who rewrote the popular soldier’s song “John Brown’s Body” as “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” intrinsically connecting John Brown the Martyr with the Jesus Christ the Savior. Bronson Alcott of Concord went even further, referring to Brown as “Bold Saint, thou firm believer in the Cross, . . . . Prophet of God! Messias of the Slave.”

John Brown filled the American imagination from before his death throughout the Civil War, when he was elevated as a heroic, myth-making figure. Nowhere was this clearer than the visual and literary manifestations of the meteors of 1859 and 1860. Pictured in Frederic Edwin Church’s The Meteor of 1860, a procession of meteors showered over the New York and New England horizons. From their first appearance, coincidentally concurrent with Brown’s death, the meteors became associated with the abolitionist himself—a sort of spiritual sign, the coming of emancipation.

The meteors echoed through the writings of Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, and others, signaling the importance of the bright and mysterious element in the night sky. For Walt Whitman, the meteor showers inspired several verses of Leaves of Grass (1819–1892). But the first work to explicitly equate Brown with the meteor of Melville’s poem “The Portent” in 1859:

Hidden in the cap

Is the anguish none can draw;

So your future veils its face,

Shenandoah!

But the streaming beard shows

(Weird John Brown),

The meteor of the war.

John Brown’s prevalence in the American consciousness was an embodiment of the tension between patriotism and individual rights, between law and principle, and between violent uprising and peaceful civil disobedience. John Brown and the issues surrounding him find continued relevance today. As both black and white soldiers sang throughout the Civil War, “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave, / His soul’s marching on!”

Click here to go to the next page: The Bust of John Brown