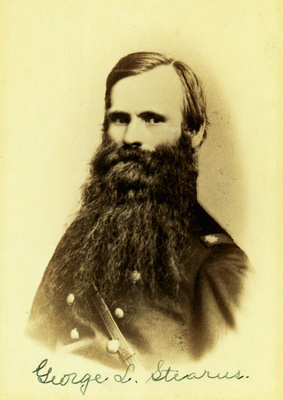

George L. Stearns: Businessman and Abolitionist

Next to the bust of John Brown sits the bust of a man much less recognized but no less noteworthy: George L. Stearns of Medford, Massachusetts. His humility in life promised him obscurity in death, but in truth Stearns had his hands in many of the important political and social issues of his time and could name as friend many who are still remembered today: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Sumner, Louisa May Alcott, John Brown, Lydia Maria Child, Thomas Starr King, Julia Ward Howe, John A. Andrew, and more. Still other famous names were of his acquaintance, including Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau, Abraham Lincoln, James A. Garfield, Andrew Johnson, and Ulysses S. Grant.

Tributes to George L. Stearns are few today, but they include two plaques, a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier, and a monument at his gravestone. One is an unremarkable plaque in the Massachusetts State House that is easy to miss even if one knows to look for it.

It reads:

"In Memoriam: George Luther Stearns. A merchant of Boston who illustrated in his life and character the nobility and generosity of citizenship. Giving his life and fortune for the overthrow of slavery and the preservation of free institutions. To his unresting devotion and unfailing hope, Massachusetts owes the Fifty-fourth and Fifth-fifth Regiments of colored infantry, and the federal government ten thousand troops, at a critical moment in the great war. In the darkest hour of the republic, his faith in the people never wavered. Of him Whittier wrote: ‘No duty could overtax him; no need his will outrun; Or ever our lips could ask him; His hands the work had done. A man who asked not to be great; But as he served and saved the state.’ Born in Medford, Massachusetts, January 8, 1809. Died April 9, 1867.”

A well-to-do businessman whose wealth came from his dedication to his businesses, Stearns donated liberally to many causes of the day. However, Ralph Waldo Emerson remarked at his funeral that “unlike other benefactors, he did not give money to excuse his entire preoccupation in his own pursuits, but as an earnest of the dedication of his heart and hand to the interests of the sufferers.... For himself or his friends he asked no reward; for himself, he asked only to do the hard work.”

The Iron: George L. Stearns

George Luther Stearns had been familiar with hard work all this life. He was born in Medford on January 8, 1809, to Luther Stearns, a doctor, and Mary Hall, a devoted Calvinist. His father died when he 11 years old, so from an early age he developed a strong work ethic to provide for his family. His first paid job was as a teenager as a clerk in Brattleboro, Vermont after which he worked at a ship chandlery (supply company) on Boston’s India Wharf. Emerson remembered him as a “man for up-hill work.” As a young adult, he and his brother began a profitable linseed oil manufactory in Medford. When linseed oil sales slumped, he had enough capital to move onto lead pipe manufacturing in Boston, an industry that he remained involved with until the end of his life.

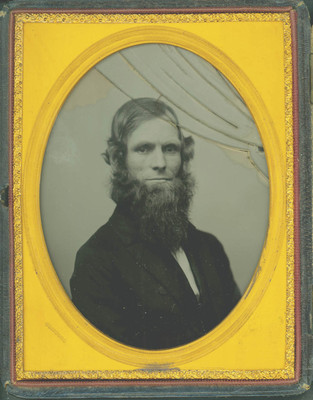

His personality was sober but optimistic, sometimes appearing naïve in the ways of the world, but he was dedicated to the cause; whatever he did, he poured his entire soul into it. In Samuel Johnson’s eulogy of him, it reads, “This most affectionate of friends, yielding like a child to every gentle persuasion, trusting with a self-abandonment that was often deceived in its objects, would yet turn to iron at the sight of injustice; and you could force adamant as easily as you could move the purpose his conscience shaped to meet it, or stay his step to the instant rectification, at whatever sacrifice.” His willingness to expend all his energy in his endeavors led to occasional illness from overexertion. He was subject to pneumonia, so his doctor instructed him to grow his beard long to keep his chest warm, which gave him an eccentric appearance.

Marriage and the Evergreens

Stearns married Mary Train of Medford in 1836, but she died just four years later. It was said that Stearns never fully recovered from her loss and never spoke of it to anyone, instead pouring himself into his work. In 1842, as he was riding home from Boston, his horse stumbled and in the fall landed upon its rider, severely injuring him. Stearns nearly lost his leg, but through the help of Amasa Walker, a renowned doctor, his leg was saved.

While recuperating from this injury, he was introduced to Mary Elizabeth Preston, whose mother was sister of the famous Medford resident and feminist Lydia Maria (Preston) Child. George and Mary continued to visit with each other and developed a relationship that resulted in marriage on October 12, 1843, in Mary’s hometown of Bangor, Maine. The two spent the early years of their marriage living with George’s widowed mother in Medford until acquiring their own property near Walnut Hill (later College Hill), a place George called the Evergreens. There they raised three sons: Harry, Frank, and Carl.

Learn more about the Evergreens and how it fits into Tufts University in the part of the exhibit titled The Stearns Estate.

It was here at the Evergreens that Stearns became involved in politics, first in local church disputes over antislavery pastors. His quest for a moral life in his early years led him to attend Universalist services, where he supported local abolitionist pastors such as Reverend Caleb Stetson. Later in his life, Reverend Samuel Johnson said of him, “The church, as an institution, did not interest him; he knew well enough that a true man carries prophet and covenant with him, and makes his communion where he goes.” He had always supported abolition, but it wasn’t until he attended the 1848 political convention in Worcester that resulted in the formation of the Free Soil Party that he became more actively involved.

John Brown and Secret Six

At first, Stearns’s political involvement strictly involved providing monetary donations to the individuals and groups he supported. In particular, he actively supported Charles Sumner, his friend and an up-and-coming lawyer and abolitionist who argued against segregation in the Roberts v. Boston court case of 1850. However, Stearns grew increasingly alarmed as the antislavery cause was threatened by the Fugitive Slave Act (1850), the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854), and the caning of Sumner for his antislavery speech (1856). Stearns began taking a more active role by aiding fugitive slaves at his home and office; funding the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company, which sent Free State settlers to Kansas to ensure that it would vote to become a free state; and in 1856 he became chairman of the Massachusetts State Committee, which provided material aid to Free State settlers being threatened by proslavery forces.

It is through his work with the Massachusetts State Committee that Stearns was introduced to John Brown in 1857. George Stearns provided Brown with the material support to continue his efforts in Kansas and later funded the raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, believing that whether the raid was a success or failure, the end result would be the same: the nation would be drawn into a final decision on slavery. Mary Stearns also provided material support by fundraising for the cause among the women of Medford.

Learn more about Stearns's involvement with John Brown in the part of the exhibit titled John Brown and the Secret Six.

After Harpers Ferry, the Stearnses attempted to reclaim the bodies of John Anthony Copeland Jr. and Shields Green, two black men who had participated in the Harpers Ferry raid and were subsequently executed, so that they could be buried in their native Pennsylvania. George Stearns wrote, “Let not the world say we honored the white but forgot the colored brethren.” Unfortunately, the attempt failed, as the bodies were taken to Winchester Medical College to be used as teaching cadavers and were unable to be retrieved.

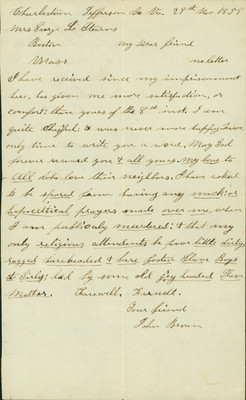

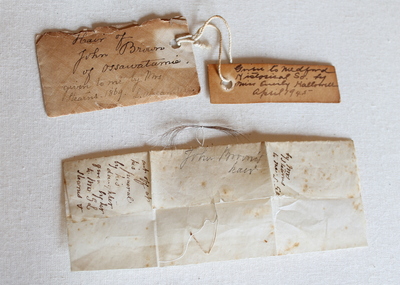

The Stearnses also attempted to arrange for John Brown’s burial at the elegant Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, until they received a handwritten letter that Brown had written to Mary Stearns before his death. In it were the following instructions: “I have asked to be spared from having any mock; or hypocritical prayers made over me, when I am publicly murdered: & that my only religious attendants be poor little, dirty, ragged, bare headed & barefooted, Slave Boys; & Girls; Led by some old greyheaded, Slave Mother. Farewell. Farewell.” The Stearnses heeded Brown’s wishes, instead providing for the schooling of Brown’s two youngest daughters in Concord, Massachusetts, at the school of Franklin Sanborn.

The Civil War and the 54th Regiment

After Harpers Ferry, George Stearns continued to solicit aid for Kansas, traveling there to see the situation for himself and attending the Republican Convention in Chicago. He campaigned for his friend John A. Andrew in the election for Massachusetts governor, which Andrew won, and he continued to provide financial support for John Brown’s family. With Civil War looming on the horizon, Stearns encouraged Governor Andrew to start preparing the military for war. Because of that, Massachusetts was the first state to respond to Abraham Lincoln’s April 1861 call for militias to quell the Southern rebellion.

In 1861, Stearns helped found a new antislavery organization, the Boston Emancipation League, which lobbied for total emancipation and produced the Emancipation League Declaration, signed by more than 100 influential people and advocating for “EMANCIPATION OF THE SLAVES as a measure of justice, and as a military necessity. . . . [Emancipation is the] shortest, cheapest, and least bloody path to permanent peace, and the only method of maintaining the integrity of the nation.” It was as a member of that league that Stearns met President Abraham Lincoln.

Returning to Boston, Stearns and other activists encouraged Governor Andrew to start forming volunteer companies of black troops. Andrew acquiesced and gave Stearns the task of recruiting black soldiers. Primarily through Stearns’s efforts, the first black regiment in the North, what he called a “true John Brown Corps,” was raised: the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. Stearns’s recruiting was so successful that an additional regiment was raised, the 55th Massachusetts.

Learn more about the 54th Massachusetts Regiment in the part of the exhibit titled 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.

After seeing his success, in the spring of 1863 the federal government offered Stearns the position of “Recruiting Commissioner for the U.S. Colored Troops.” He assented, was bestowed the rank of major, and was sent to Tennessee. Stearns immediately went to work creating recruiting centers, influencing public opinion to accept black soldiers, and getting to know the local black community. He found that black men were being forcefully pressed into duty as laborers for the U.S. Army. Believing the military would not investigate properly, Stearns encouraged black men to enlist or to volunteer to work on the railroad in order to impress the authorities and the public. His strategies helped turn white public opinion in favor of black troops. He also found that some potential recruits were afraid to enlist because they were worried about supporting their families, so he worked to provide for the families of black refugees displaced by the war and to arrange jobs for soldiers’ wives. In response to illiteracy among freed slaves, Stearns instigated schooling for new trainees.

In the three months Stearns was in Tennessee, he built several recruitment centers and recruited more than 6,000 troops (six regiments’ worth). He might have had even more success had not his earnest disposition and diligence clashed with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, whom he considered haughty and ineffective. He was also frustrated by the bureaucracy of the government and infuriated by its failure to hold to its promises to treat black troops equally to white troops. He was confident he could be more effective as a private citizen than as a government lackey. In January 1964, he resigned from his post and returned to his family in Medford.

Change of Fortune

But “retirement from public life” wasn’t the end of Stearns’s advocacy. He bought two abandoned cotton plantations near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, to provide jobs for black women and children while their soldiers were away. He financed several antislavery publications in the North, including The Right Way. He continued running his lucrative lead manufacturing business. After the Civil War ended, he encouraged antislavery societies not to disband so that they could work towards equal rights and treatment of black citizens. His friends and neighbors appealed to him to run for Congress, but he declined.

Then in 1866, Stearns experienced a change in fortune. As he had said years before, “Emancipation has been hard on my purse,” and a drop in gold prices and several failed investments left him in dire financial straits, so much so that he wanted to sell the Evergreens. Mary Stearns would hear nothing of it, so instead his son Harry left his courses at Harvard and came home to help his family. Despite his situation, he couldn’t refuse when the following year his friend Samuel Gridley Howe asked him to aid in fundraising for the Cretans who were rebelling against the Turks. The two traveled to New York and had plans to travel directly to Crete in the spring.

However, in February of 1867, Stearns heard about a new method of manufacturing lead pipe that could end his financial woes. He was in New York testing the pipe in April when he fell ill with pneumonia. His wife was called for, but the treatments of the homeopath she brought with her failed to cure him. He died in his hotel room in New York City on April 9, 1867.

Mary escorted George’s body back to Medford, where more than fifty friends attended a private funeral held at the Evergreens. The funeral was presided over by Reverend Samuel Longfellow (brother of the better-known Henry Wadsworth Longfellow), and Ralph Waldo Emerson and Theophilus Parsons both offered eulogies. George Stearns was a “a man who wanted absolutely nothing for himself,” Parsons remembered.

The next week, there was a public memorial service held at the Medford Unitarian Church, where Emerson again spoke, declaring of Stearns that

"[There is] hardly a man in this country worth knowing who does not hold his name in honor. . . . For the Spirit of the Universe seems to say: ‘He has done well; is not that saying all?"

Stearns’s body was interred at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, where a monument to his memory reads:

George Luther Stearns: The virtues of this rare man were celebrated at this death by the eloquence of Emerson, and in the poetry of Whittier. An unexampled honor, in his time he sheltered the exiled Hungarians together with John Brown. He saved Kansas to freedom. Almost alone in 1863 he organized the colored regiments, which turned the scale in favor of the Union cause. He expended a fortune in public and private benefactions.

Click here to go to the next page: The Stearns Estate