The Stearns Estate

The Stearns Estate (The Evergreens)

It’s easy to miss. Hundreds of students and locals walk by it every day, but how many of them have paused to read the nondescript plaque on a rock in front of Cousens Gymnasium on Tufts University’s Medford-Somerville campus?

Site of the Stearns Estate

A waystation on the Underground Railroad, a haven for slaves seeking freedom

1850–1860

Placed here by members of the Tufts community, who continue to honor the tradition of sanctuary

Dedicated April 8, 1987

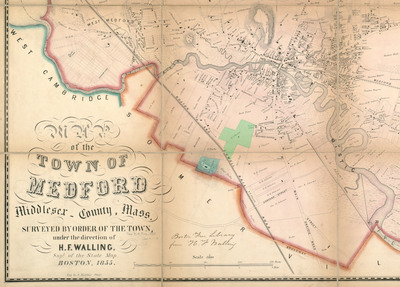

In 1845, George L. Stearns decided to move his young family into a derelict mansion near Walnut Hill on 26 acres of farmland that had once belonged to Isaac Royall Jr., one of Medford’s early prominent citizens—and the area’s largest slaveholder. The land had been abandoned by Royall, a Loyalist, just prior to the American Revolution.

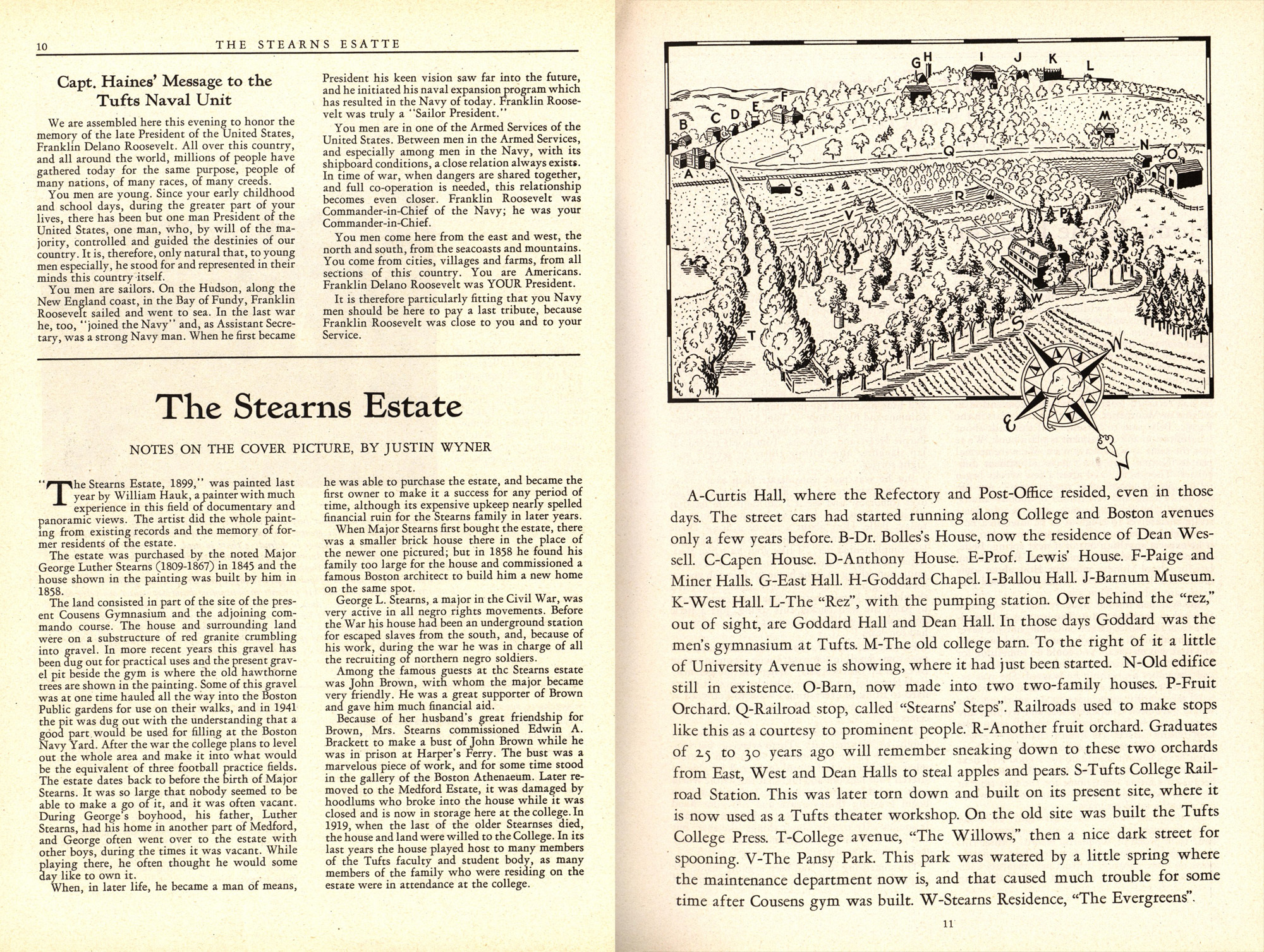

George fixed up the house, which he called the Evergreens, and filled the land with orchards, fields, a barn, and a greenhouse. The property was far enough from Medford proper that he and his wife Mary could live in peace in a bucolic setting, but it was close enough that he could keep an eye on his mother. It was also within commuting distance to Boston and Charlestown, where George had his business interests. As the Stearnses’ wealth increased, their social circles expanded to include the high society of not only Medford but also the neighboring communities of Boston, Concord, and beyond. They began hosting elegant parties at the Evergreens, whose attendees included names that are still famous today, such as the Emersons and Alcotts of the Concord literati, politician Charles Sumner, and many more.

Perhaps the most important celebration held at the Evergreens was what George called the “John Brown Party”: the celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation held on January 1, 1863. Joshua B. Smith, a black caterer operating out of Boston, provided the refreshments and numerous local celebrities attended, including abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips; preacher Samuel Longfellow (brother to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow); and authors Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bronson and Louisa May Alcott, Franklin Sanborn, Samuel Sewall, and Julia Ward Howe.

In 1850 and the years that followed, George was appalled by the passage and enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act in Boston. He purchased a revolver and vowed never to let any fugitive slave seeking refuge at the Evergreens to be returned back to slavery. It wasn’t long before his vow was tested.

One morning in 1853, George discovered a black man asleep in his barn. The man’s name was William Talbot and he had been enslaved as a jockey at a plantation in in Alabama. Talbot’s master had taken him to Philadelphia to compete when Talbot saw a chance to escape. He made his way to Boston and sought refuge with the free black population of Beacon Hill in Boston. They had sent him to the Evergreens, where the Stearnses hosted him for more than month. One day when the Stearnses were away, a pair of federal marshals showed up at the estate looking for Talbot, who hid under the bathroom floor while the groundskeeper confronted the two and they left. That night, fearing Talbot was in danger, George took him to Lowell, where he boarded a train to Montreal and freedom. George’s son Frank writes that Talbot returned to Boston three years later and at that time George helped set him up as a barber in Harvard Square.

We do not how many fugitive slaves the Stearnses helped. There were rumors of escape tunnels beneath the Evergreens, but investigations have never found any evidence of that claim. It is possible Talbot was the only one who was aided at the Evergreens, though there are records that indicate George helped fugitive slaves from his office in Boston. What we do know is that during the Civil War and even after the abolition of slavery, the Stearnses used their resources to fight for equal rights for black citizens. Even more unusually even for abolitionists at the time, he treated black citizens as his equals. He employed black men and women, provided for black soldiers’ families, and gained the respect of the black communities he worked with.

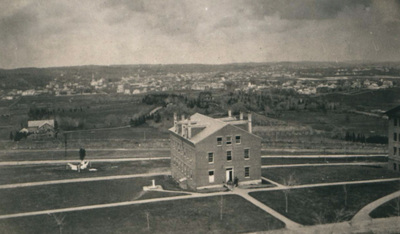

Both George and Mary Stearns dwelled at Evergreens until the ends of their lives, with George's passing in 1857 and Mary in 1901. Although George had witnessed the founding of Tufts College on the hill next to their property in 1852—and Henry had taken some courses at Tufts—it was Mary who would have seen it grow from a single building on the top of the hill to a sprawling suburban college. From her property, set up on a slight hill, she would have witnessed hundreds of students embarking and disembarking at College Hill station next door, and she may have occasionally spotted couples sneaking away to the romantic, tree-lined College Avenue, nicknamed "The Willows." Many Tufts students during those years had fond memories of sneaking away to the Stearns Estate to nick apples and pears from the orchards. Mary must not have minded too much; she left the estate to her two living sons for the rest of their lives, after which the property was to be given to Tufts College.

Cousens Gymnasium

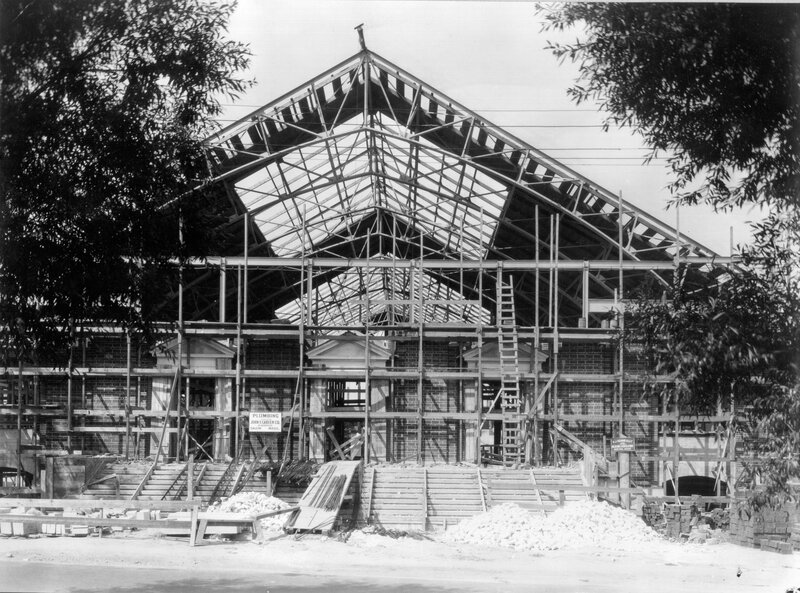

Tufts College acquired the Stearns Estate in 1920 with the passing of Harry L. Stearns. Unfortunately, within a short time the mansion was vandalized and set alight, forcing its demolition in 1922. By 1931, Cousens Gymnasium was built along College Avenue near where the house had been located. The willows that once lined College Avenue were cut down as the street was widened and the property opposite the Stearns Estate, once a clay pit, was turned into a parking lot.

Stearns Village

In 1945, Hamilton Pool was added to Cousens Gymnasium. That year and the following year, Tufts faced a severe housing shortage as students returned from World War II. In the spring of 1946, emergency housing for student veterans was set up next to Cousens Gymnasium. This complex of twelve temporary buildings housed around 80 families at time, with 40 children living there in its first few years. In the 1950s, the complex was reported to have had the highest birthrate in Middlesex County. The wives of male students, called “bookworm widows,” founded the Tufts Wives Club to facilitate babysitting. This club evolved into the Stearns Village Nursery School, which was the precursor to the current Eliot-Pearson Children’s School, which was built on the property in 1962.

Stearns Village was never intended to be permanent and its buildings lasted only ten years before they were no longer inhabitable. The last residents left in 1955 and the last building was torn down in 1956. The area became the “Stearns Lot,” providing parking for the gym and the Eliot-Pearson Children’s School. Next door, the Cousens Gymnasium saw several expansions: in 1979 to provide coeducational facilities; in 1993 with the addition of the Steve Tisch Sports and Fitness Center; in 1997 with the intramural Chase Gym; and in 1999 with the Gantcher Family Sports and Convocation Center, which was built over the Stearns Lot.

The Legend of the Stearns Estate

Today, the memory of the Stearns Estate lives on only in the name of Stearns Avenue and on the plaque in front of Cousens Gym. However, behind the Elior-Pearson School and the Gantcher Center is a small hill that leads to an empty field where neighborhood children run and play. If you climb the hill and turn towards the southeast, you can catch a glimpse of the Bunker Hill Monument, which looks today as it would have when George and Mary Stearns still dwelt in the Evergreens 150 years ago. Turning towards the south, you can see the skyscrapers of downtown Boston and Back Bay, a testament to how much Boston has changed in the last century and a half. And turning towards the southwest, you can view glimpses of Tufts University through the trees and still hear the laughter of students on the hill.

Click here to go to the next page: 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment