54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment

Raising a True John Brown Corps

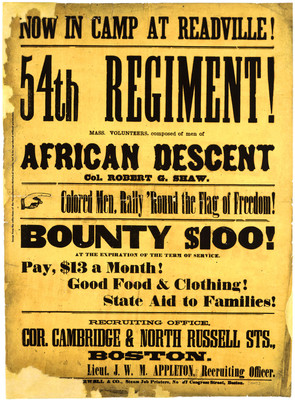

As the Civil War commenced, George L. Stearns found it imperative to look for ways of encouraging abolition other than emancipation. He played a pivotal role in the recruitment and organization of troops for the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the first black regiment raised in the Union. After organizing a committee whose sole aim was the recruitment of black soldiers for the military, Stearns prepared a subscription paper to raise the necessary funds. He intended “to make this a true John Brown Corps,” drawing on the legacy of John Brown in his search for members to prove to America that the black soldier was as worthy and valuable as the white soldier.

Near the end of February 1863, Stearns traveled to Rochester, New York, to meet with Frederick Douglass, a former slave and the editor of the antislavery newspaper The North Star. Douglass agreed to assist with recruitment ads in his newspaper and his two sons enlisted in the Union army. Stearns poured his entire heart and soul into his recruiting efforts. He later wrote that he “had so much to do with the formation of it that all, both officers and men, hold the place of relatives in my affections.” Back in Boston, Beacon Hill community leader and former slave Lewis Hayden was one of the biggest advocates for black enlistment.

Freedom's Army

There were many obstacles to black enlistment. In some cities, white residents rioted when they heard about black recruitment, forcing it to be performed under the radar. Not enough men enrolled in Massachusetts, so Stearns was forced to recruit in other states and even in Canada, where many escaped American slaves had taken refuge, free from the threat of return to bondage under the Fugitive Slave Act. Conditions in the army for black soldiers were not equal to those of white soldiers: black troops were paid half as much as white soldiers and were not permitted to be commissioned as officers. Despite those challenges, it wasn’t long before Stearns, Hayden, and their aids had sent enough recruits back to Boston to fill two regiments, leading to the creation of a second regiment, the 55th Massachusetts Infantry.

Robert Gould Shaw, just 25 years old, was selected as the 54th Regiment’s first commander. From the beginning, Colonel Shaw was a strong advocate for his troops. When state leaders tried to set up separate training for black recruits, Shaw flat out refused to serve unless his troops were trained at Camp Meigs in Readville, where the other regiments trained. Leaders gave in and for two months the 54th trained at Camp Meigs, just a few miles from Boston.

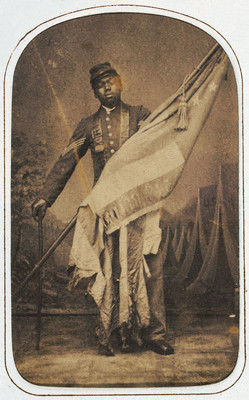

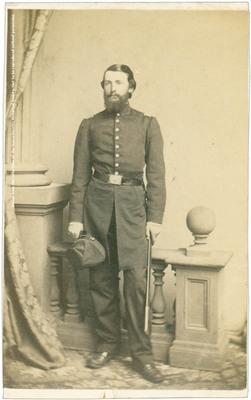

The soldiers of the 54th had a wide variety of backgrounds. Some had escaped slavery, while others were freeborn. Some were Massachusetts natives, while others came from states throughout the Union. All of the commissioned officers were white; black officers existed but were not allowed to be commissioned. Sergeant Henry F. Steward had been an active recruiter in his home state of Michigan. A photograph of him presents a stately image—he may have paid the photographer extra to tint the breastplate, buttons, sword, cap, and pants. Another photograph depicts Private Alexander Johnson, a 16-year-old from New Bedford, Massachusetts. Colonel Shaw referred to Johnson as “the original drummer boy,” honoring the young man for his service. In the field, Johnson carried important messages between the officers and later witnessed the death of Colonel Shaw at Fort Wagner.

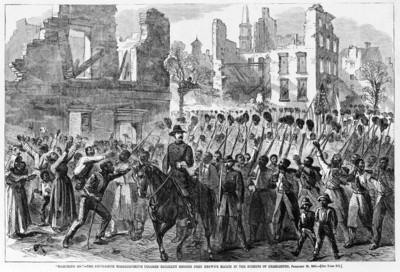

On May 28, 1863, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment marched through Boston on its way to the South. As the 1,007 black soldiers and 37 white officers marched through the streets, William Lloyd Garrison, editor of the antislavery newspaper The Liberator, stood on a nearby balcony with his hand held atop a plaster bust of John Brown, symbolically projecting Brown’s spirit and permitting the figure to witness the results of his aborted campaign. As the troops passed by the Old State House, near the place where Crispus Attucks, the black patriot, fell in 1770 as the first blood shed for American freedom, the band spontaneously started playing “John Brown’s Body.” On the sidelines, black historian William Cooper Nell thought of Thomas Sims and Anthony Burns, who had escaped slavery and come to Boston only to be returned to slavery under the Fugitive Slave Act, and thought about the poignancy of the moment.

As the soldiers boarded the ships towards Charleston, Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew addressed the men: “I know not, where in all human history to any given thousand men in arms there has been committed a work at once so proud, so precious, so full of hope and glory as the work committed to you.” His message was one of acknowledgement and counsel; while the fight for emancipation was firmly established, the struggle for equality would require the same energy with which Brown campaigned.

Second Battle of Fort Wagner

Over the course of the ensuing months, the 54th Regiment established itself on the battlefield as strong and courageous soldiers. In one of the regiment’s early battles, the Second Battle of Fort Wagner outside Charleston, the regiment suffered its highest casualties of the war—54 dead, including their commander; 179 injured; 48 whose whereabout were never accounted for—and were forced to retreat. However, from their darkest hour came their greatest triumph: they had proved their loyalty and valor to a skeptical country that doubted them simply because of their race.

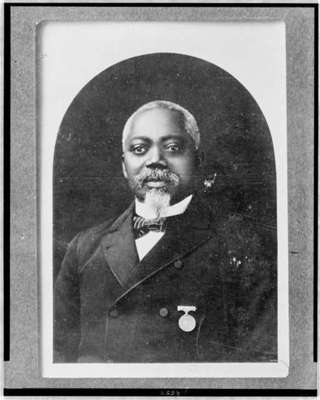

America’s first medal of honor given to an African American was awarded as a result of the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, but it took almost 50 years. During the battle, Sergeant William Carney—formerly enslaved—saw the regimental colors fall to the ground. He rescued the American flag, suffering injuries in the process, but was able to keep it from falling into the enemy’s hands. When he reached safety, he exclaimed, “Boys, I only did my duty. The flag never touched the ground.” In 1900, Carney was awarded the Medal of Honor. Because his actions took place before those of other African Americans awarded the medal, he is considered its first black honoree.

After the death of Colonel Shaw, Edward “Needles” Hallowell of Medford took command of the 54th. Hallowell’s two brothers were also involved with the 54th and 55th Regiments; Richard P. Hallowell worked with George L. Stearns to recruit soldiers, while Norwood Penrose Hallowell became the commander of the 55th Regiment. Colonel E. H. Hallowell survived the war but died in 1871, most likely due to injuries he sustained in the Second Battle of Fort Wagner and other battles.

Equal Pay Controversy

By law, black soldiers were only allowed to receive the wages of a laborer, which was half as much as a soldier made. As a result, the 54th and the 55th regiments refused to accept wages that were unequal. When Governor Andrew made an agreement with the state legislature to increase black soldiers’ wages slightly (but still not as much as white soldiers’ wages), he was mystified when the troops still refused to accept their pay. One soldier explained that the regiment would not take the money because otherwise the world would believe they were “holding out for money and not from principle.” As the months wore on, the soldiers’ families suffered from the lack of income, but the soldiers held firm.

It wasn’t until 18 months later, in June 1864, that Congress passed a bill permitting equal pay for equal service. The law had stipulations, however: only enlisted troops who had been free men as of April 19, 1861, would be authorized full back pay. Many of the troops who had joined the 54th and 55th after the start of the war were in fact freed or escaped slaves from the south. However, Colonel E.H. Hallowell devised a workaround. As a Quaker, he did not believe slavery was a legitimate institution, so he formulated for his troops what is known as the “Quaker Oath”: “You do solemnly swear that you owed no man unrequited labor on or before the 19th day of April 1861. So help you God.” In this way, all soldiers received their just—albeit late—wages.

Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Regiment Memorial

On May 31, 1897—Memorial Day—a grand ceremony was held on the Boston Common as the Robert Gould Shaw and 54th Massachusetts Regiment Memorial was dedicated. In attendance were the last surviving of members of the original 54th Regiment, as well as Norwood Penrose Hallowell and Richard P. Hallowell. Noted educator Booker T. Washington, first president of Tuskegee University, spoke. He noted,

“[Colonel Shaw] would have us bind up with his own undying fame and memory, and retain by the side of his monument, the name of John A. Andrew, who, with prophetic vision and strong arm helped make the existence of the 54th possible; and that of George L. Stearns, who, with hidden generosity and a great sweet heart, helped to turn the darkest hour into day, and in doing so freely gave service, fortune, and life itself to the cause which this day commemorates. Nor would he have us forget those brother officers, living and dead, who, by their baptism in blood and fire, in defense of the union and freedom, gave us an example of the highest and purest patriotism.”

The monument was 32 years in the making. In 1865, Governor Andrew had called a meeting at the State House to form a committee to investigate creating a memorial for Robert Gould Shaw. Committee members included Governor Andrew, Charles Sumner, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Joshua B. Smith, Frank W. Bird, and George B. Loring. Eventually, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens was chosen to create the monument. It took him 13 years to complete what is considered one of the greatest pieces of public art in America.

The courage and dedication of the 54th Regiment are still remembered today. George L. Stearns predicted correctly when he wrote in 1865,

"History will yet vindicate the patriotism of our colored citizens of the free States. When their offers of service in the beginning of the war were rejected with contumely, they promptly volunteered at the call of their country when she needed them to help conquer a relentless foe. Every battle-field on which they were permitted to face the enemy bears witness to their steady valor, and their perfect discipline.”

Click here to learn about the Collections at Tufts used in this online exhibit.