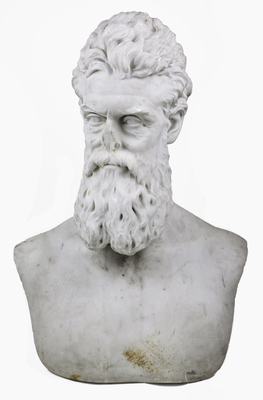

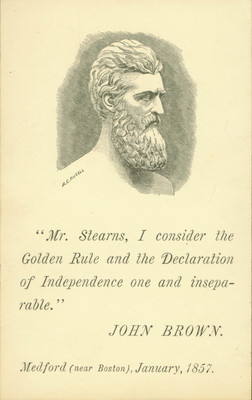

The Bust of John Brown

The Nameless, Noseless Bust

For decades, the noseless bust of a bearded man lay in storage at Tufts University. Nobody knew who it was or where it had come from. It changed location several times, but it was usually identified as “Bust of an Unknown Man by an Unknown Sculptor,” with the occasional addition of “Brown” as the sculptor.

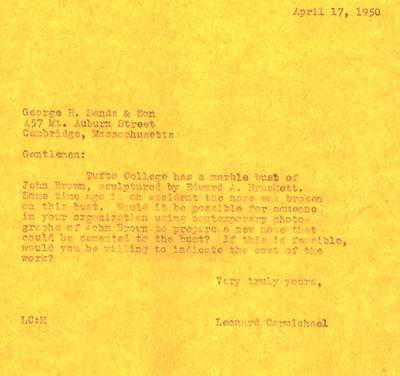

In 2015, the university’s art collection registrar, Laura McDonald, was researching unidentified artworks in the University Archives. While looking through a folder titled “Art objects, Inventories, 1854 – 1982” which was part of the Archives’ Facilities Management Records she came across a short note from 1950 written by university president Leonard Carmichael inquiring about fixing the broken nose of a bust of John Brown. McDonald put two and two together and was able to identify the nameless bust. But that was just the first exciting discovery.

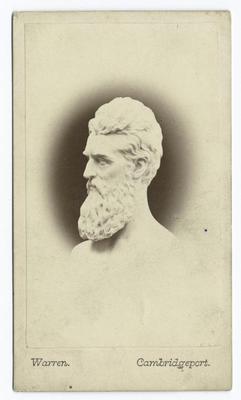

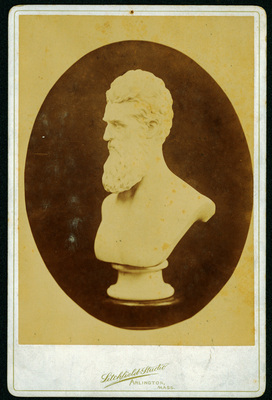

The Creation of the Bust

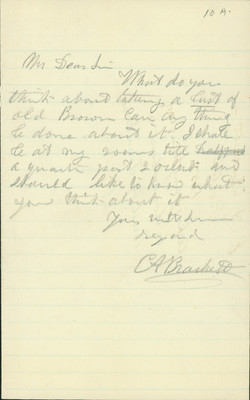

In November of 1859, Winchester-based sculptor Edward Augustus Brackett contacted Mary E, Stearns in Medford. His petition to Mary Stearns arrived at the recommendation of Samuel Gridley Howe and Mary's husband George L. Stearns, who had fled to Canada for their own safety following John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. Mary Stearns provided $120 in gold coins for the expenses incurred in Brackett’s travel to Virginia, where he would meet Brown to sketch his features and take measurements for the formation of a bust. If Brown refused, according to Mary Stearns, Brackett was instructed to say “that he has come at the express wish and expense of Mrs. Stearns, and that she will be deeply disappointed if he returns without the measurements.” This was a compromise of sorts for Mary Stearns, whom Brown had refused to allow to come to tend him in his jail cell.

Edward A. Brackett arrived at Harpers Ferry before the conclusion of Brown’s trial, sometime before the Brown’s guilty verdict was announced on November 12. Traveling with letters of introduction to the leader of the Senate investigative committee and to the prosecuting attorney, Brackett was met with cool civility. Many were aware Brackett was from the North and were suspicious of his possible abolitionist motives. As a result, he was denied access to Brown’s jail cell. However, he eventually gained sympathy from the assistant jailer, who recalled having met Brown during his time in Kansas. The assistant jailer opened the door to Brown’s cell while Brackett took measurements from the doorway, refusing to enter the cell further to ensure the jailer could honestly claim he did not allow Brackett to enter the cell.

Brackett returned to Boston soon thereafter and completed the bust in 1860. Perhaps a dozen plaster versions were cast, the recipients of which included Haitian President Guillaume Fabre Nicolas Geffrard, French poet and novelist Victor Hugo, and the editor of the antislavery newspaper The Liberator, Wendell Phillips. The sole marble bust, however, was reserved for Mary Stearns.

The Legend of John Brown's Bust

The marble bust of John Brown was displayed at the Boston Athenaeum until it was officially unveiled at the “John Brown Party,” as George L. Stearns called it, held at his Medford estate on January 1, 1863, to celebrate the first day the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. Earlier in the evening, a Jubilee Concert had been held at the Music Hall and its attendees had been invited to an afterparty at the Stearnses’ home. Many famous names were in attendance, including transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson, poet and author Julia Ward Howe, authors Bronson and Louisa May Alcott, Franklin Sanborn of the “Secret Six,” abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips, as well as other antislavery supporters. The bust was displayed prominently as Emerson read his “Boston Hymn” and Howe gave a rendition of her “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

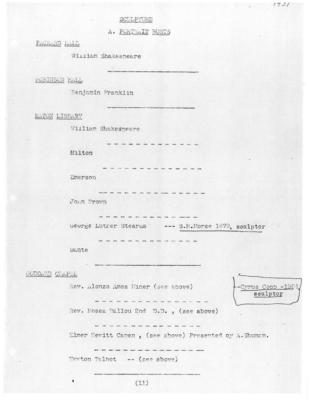

Brackett’s bust of the martyr soon became an icon of the abolitionist movement, even after legal abolition had been achieved. The bust’s image was displayed on numerous cabinet cards (photographs) that were shared amongst antislavery circles. Sculptor Edmonia Lewis, who was of both African and Native American descent, was mentored by Brackett. She sculpted medallions based on the bust to sell and with those profits, she was able to pay her way to Italy, where she became an internationally known sculptor.

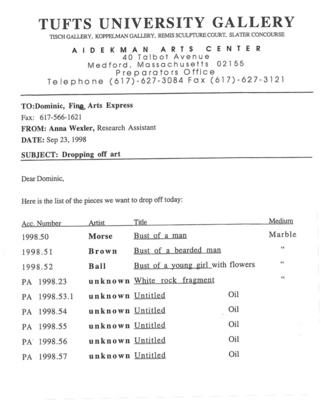

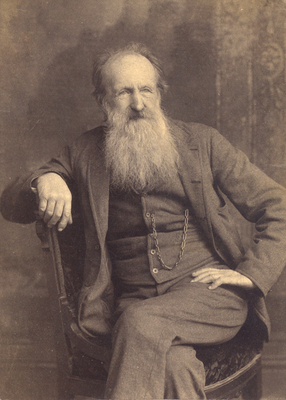

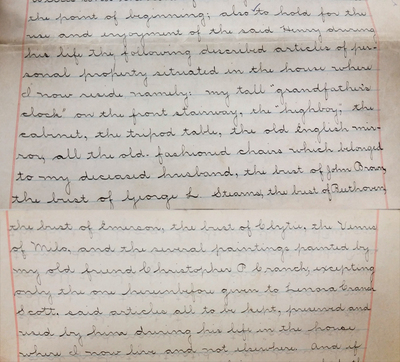

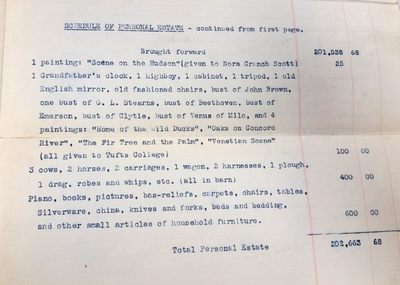

The bust of John Brown remained on display near the stairway of the Stearns Estate for half a century. After her husband’s death, Mary Stearns continued to send plaster copies to institutions and individuals she was sympathetic to, including the Kansas Historical Society and her friend Booker T. Washington. In 1879, she commissioned from Samuel Morse a bust of her husband to display alongside that of John Brown. When Mary Stearns died in 1901, she left the busts to her two living sons, Henry and Frank, with the stipulation that the busts and her estate be gifted to Tufts University (then called Tufts College) after their deaths.

Donation to Tufts University

The Stearns Estate was granted to Tufts College in 1920 after the deaths of Henry and Frank Stearns. The bust of John Brown (and likely the bust of George L. Stearns as well) remained in the Stearns mansion until 1922―it is believed that the bust of John Brown lost its nose and eyebrow during this time period. The busts were eventually brought up the hill to campus and their exact trail after this point is nebulous, but it is believed that both busts were on display at the Eaton Library for many years, where they may have suffered superficial damage from the doodling of bored students.

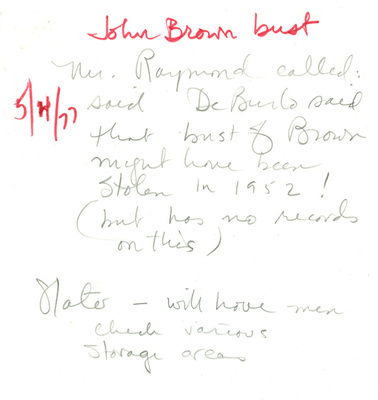

In 1950, Tufts President Leonard Carmichael send a request to a conservator in Cambridge inquiring about repairing the bust. The university has no record of any reply. It is likely that soon thereafter the busts were placed in storage, possibly next to a leaky waterpipe in Ballou Hall, and forgotten. There was an attempt made to locate the bust in 1977, but the only lead was a tip that the bust may have been stolen in 1954. The busts remained, unidentified, in storage on campus until 1998, when they were taken to an off-campus fine arts storage facility in South Boston.

Rediscovery and Restoration

In 2014, Tufts Art Collection Registrar Laura McDonalad hired graduate student Jessica Camhi to conduct archival research through at Tufts Digital Collections and Archives examining early documents related to objects in the Permanent Collection. It was among these University records that McDonald encountered the 1950 Carmichael note that led her to solve the puzzle: the noseless bust in storage was the bust Edward Augustus Brackett had made of John Brown. The more she learned about the bust and its history, the more she knew it needed to be restored. But how could she replace its nose?

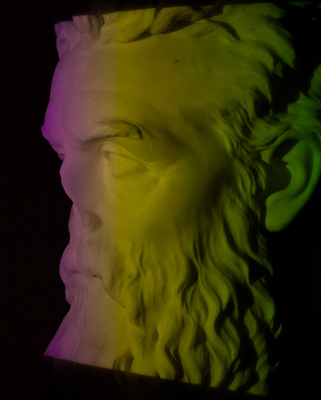

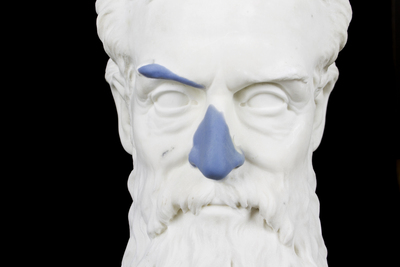

The answer lay in state-of-the art technology. In 2016, Sean O'Reilly of the Boston-based 3D Printsmith was called in to help. One of the few remaining plaster versions of the bust was located at the Boston Athenaeum. That plaster bust was scanned to create a 3D image of what the nose was supposed to look like. That image was combined with a scan of the damaged bust to create a 3D model of the missing nose and eyebrow, which were later printed in blue plastic using 3D printer technology. From those plastic models, a rubber mold was fabricated in which to cast the final pieces in white plaster. Sculpture conservator Rika Smith McNally then cleaned the bust and attached the new plaster nose and eyebrow, painting them to match the marble exactly. Now even the most discerning eye can’t tell where the original marble ends and the new plaster nose starts.

The bust of George L. Stearns was also cleaned in preparation for exhibition. Now the two sculptures sit side by side once again: John Brown and George L. Stearns, the Magnet and the Iron, as they should be.

The busts of John Brown and George L. Stearns on display in the Tisch Library, 2017

Click here to go to the next page: George L. Stearns: Businessman and Abolitionist