Edmonia Lewis

Edmonia Lewis is considered the first American sculptor of color to gain an international reputation. As a woman of African American and Native American (Chippewa) heritage, Lewis faced significant challenges in her attempts to become a professional sculptor, so much so that she left for Europe to escape others’ obsession with her background. She wrote, “I was practically driven to Rome in order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color. The land of liberty [America] had not room for a colored sculptor.”

Lewis was an orphan who attended Oberlin College with the help of her brother. While at Oberlin, two white students accused her of poisoning them. Before her trial, locals took matters into their own hands and abducted her and beat her. At her trial, she was declared innocent of all charges, but she was nonetheless not permitted to finish her degree. Instead, she traveled to Boston with an introduction to prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison in her pocket.

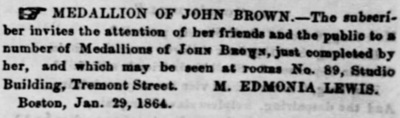

In Boston, Lewis saw the statue of Benjamin Franklin in front of the old city hall and determined to become a sculptor to be able to create something like that. Garrison introduced her to Edward Augustus Brackett, who had sculpted John Brown several years earlier. Lewis remarked, “A man who made the bust of John Brown must be a friend of my people.” Lewis trained under Brackett for a year or two, using his works as models and creating portrait medallions of John Brown to sell to earn money. The two eventually split ways due to an unspecified disagreement.

Some of Lewis’s works include busts of Abraham Lincoln, Robert Gould Shaw, Charles Sumner, John Brown, and figures from the Bible and Greco-Roman mythology. She based at least six sculptures on The Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who later sat for a sculpture in her studio in Rome.

In 1864, Lewis sculpted a bust of Robert Gould Shaw, the first commander of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. She had seen the 54th march out of Boston the previous year and was struck by Shaw’s dedication to the cause of abolition. She requested a photograph of Shaw from Lydia Maria Child, but Child refused to give it to her, claiming she would not be able to do justice to this revered figure. Lewis nevertheless created the bust. When Child saw it, she remarked, “[Lewis] had succeeded so well that those familiar with the photographs of the young hero could not fail to recognize the bust. It has some imperfections as the work of beginners must necessarily have, but it was quite remarkable.” (This patronizing attitude was typical of Child throughout Lewis’s time in Boston.) Shaw’s family approved of the bust and Lewis subsequently sold a hundred plaster replicas of the Shaw bust at the Soldiers’ Relief Fund Fair in November 1864.

After observing Lewis at work on the Shaw bust, poet Anna Quincy Waterston wrote,

‘Tis fitting that a daughter of the race

Whose chains are breaking should receive a gift

So rare as genius. Neither power nor place,

Fashion or wealth, pride, custom, caste, nor hue

can arrogantly claim what God doth lift

Above these chances, and bestows on few.

By 1865, Lewis had earned enough money to pay for her passage to Rome, where she lived and worked many years. At the time, it was the custom for most sculptors to create clay models themselves then hire laborers to shape the marble versions, but in Rome, Lewis, she was one of the few sculptors to do the sculpting herself in order to prove to critics that she was not claiming others’ work as her own.

Lewis continued to live and work in Europe for the rest of her life, occasionally traveling to the United States for the presentation of her work. The last few years of her life are shrouded in mystery—and for decades were in fact entirely unknown—but recent investigation has discovered that Lewis died in London in 1907 and was buried in an unmarked grave at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery, an obscure end to her very public life.