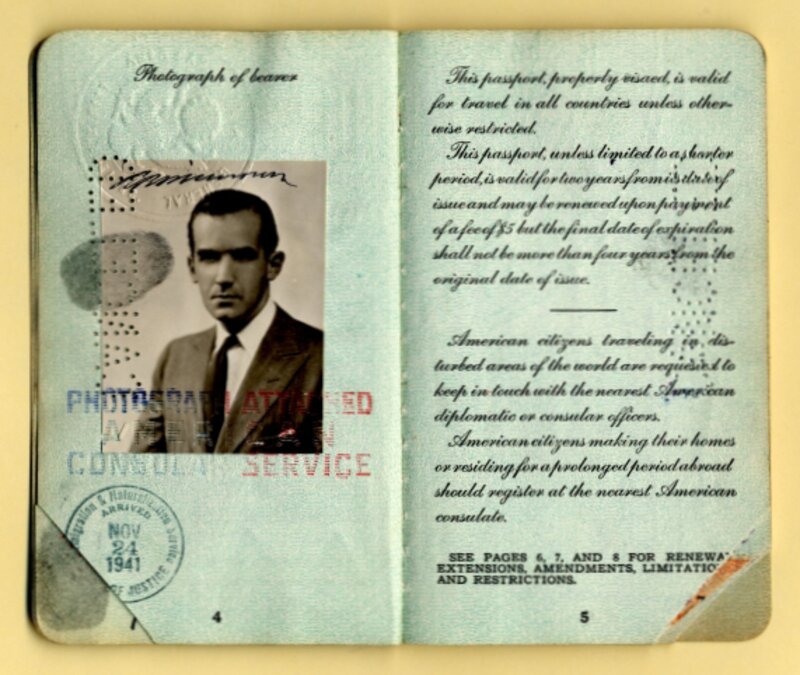

Murrow at CBS, Europe, 1935/37-1946

Radio News Broadcasting and CBS in the Twenties and Thirties

In the 1920s and 1930s, newspapers and news agencies in the United States and Europe perceived a threat to come from a brand new medium: radio, and they attempted to protect their industry by restricting radio news broadcasting both at home and from abroad. Still, the BBC began to do some radio news broadcasting as early as 1927, and by the mid 1930s, BBC radio news had come into its own. On the American side, it took a few years longer. Starting in 1936, the American veteran reporter and broadcaster Raymond Gram Swing(1887-1968) offered news analysis in his program World Events, which were five weekly broadcasts explaining the rise of Hitler for Mutual Broadcasting System (MBS). Max Jordan (1895-1977), working for NBC, did an onsite news broadcast in 1934 about the assassination of chancellor Engelbert Dolfuss in Austria and continued to do international onsite news broadcasts in the following years. News roundups from several national or international locations, although not frequent, were organized repeatedly in the 1930s, and the National Socialist government in Germany effectively incorporated recordings for their news broadcasts.1 Yet, at CBS the world of radio news was different and more limited. When Murrow was sent to Europe as CBS Director of Talks in April of 1937, CBS neither allowed news broadcasts nor news roundups, let alone recordings. Without recording sounds or interviews, the kinds of broadcasting that could be done during a war were severely restricted. In its stead, CBS chose to organize lectures and speeches given by famous individuals roughout the thirties and had staff read newspaper headlines and stories over the air. Murrow and his team of correspondents changed all of this. Instead of organizing cultural talks or choir performances, as they had largely done until fall of 1938, Murrow and his 'Murrow Boys' came to make regular news broadcasts, albeit still hobbled by the ban on actual recorded sounds or interviews. Here, the breakthrough was their news roundup of March 1938 after the Anschluss of Austria, a broadcast done to counter Max Jordan's scoop of that story for NBC. Then, with the Sudetenland crisis in the fall of 1938, Murrow got the green light to create a daily news feature, the CBS World News Roundup. It was not until late in the war, however, that Murrow and others managed to persuade CBS to allow them to use recordings for their broadcasts. In the meantime, CBS's publicity machinery won the publicity war against its competitors NBC and MBS back home.2 To cover up for the fact that Max Jordan from NBC first reported about the Anschluss in Austria, just as Jordan later was the first to broadcast the text of the Munich Pact Agreement, CBS published a handsome and well-written booklet right after the Anschluss called Vienna, March 1938: A Footnote to History, creating the impression that CBS alone had done and dominated the story. Other strategies included CBS organizing dinners and large receptions for its correspondents, interviews, photo opportunities, publications of scripts and recordings, and CBS encouraged and facilitated the Murrow Boys to write books about their experiences as war correspondents. In hindsight, after the war, all this made it appear as if CBS had done it alone and done it best. Ratings had been won as well as sponsors.

Murrow at CBS, USA, Fall 1935 - Spring 1937

Before leaving for London, Murrow spent a year and a half as CBS Director of Talks to Coordinate Broadcasts on Current Issues in New York organizing political, educational, and religious speakers for the radio. Although this was a purely administrative position, it was during this time that he did his first news broadcast. He was tutored by Robert Trout, an established radio broadcaster at CBS, and read the news for the first time on Christmas Eve 1936, using Trout's script. A couple of months later, in February 1937, Edward Klauber, then vice-president of CBS and Murrow's new mentor, acted on Fred Willis' suggestion and offered Murrow the position as European Director of Talks. Cesar Searchinger, CBS's previous European director, was about to resign, and Klauber had been dissatisfied with NBC's better coverage from the continent. Murrow accepted.

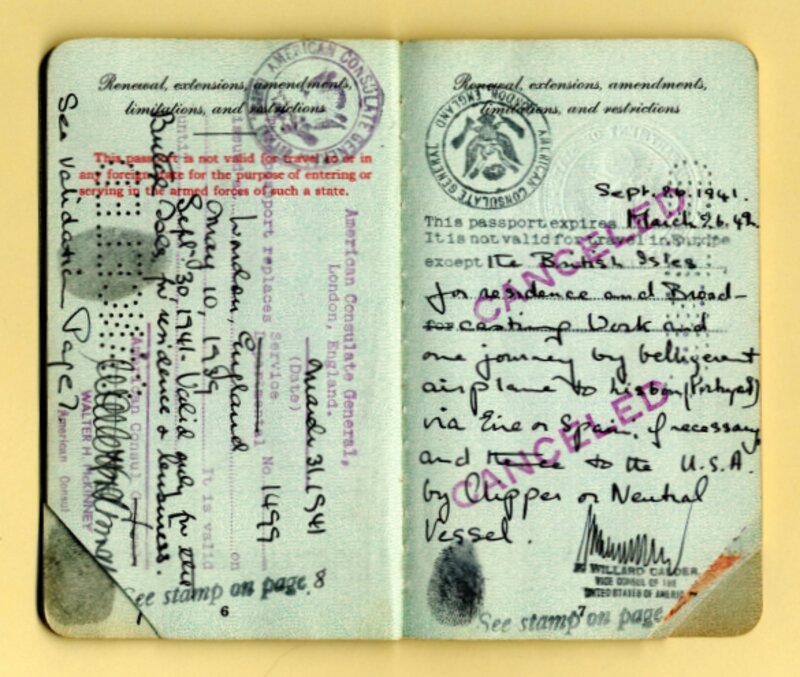

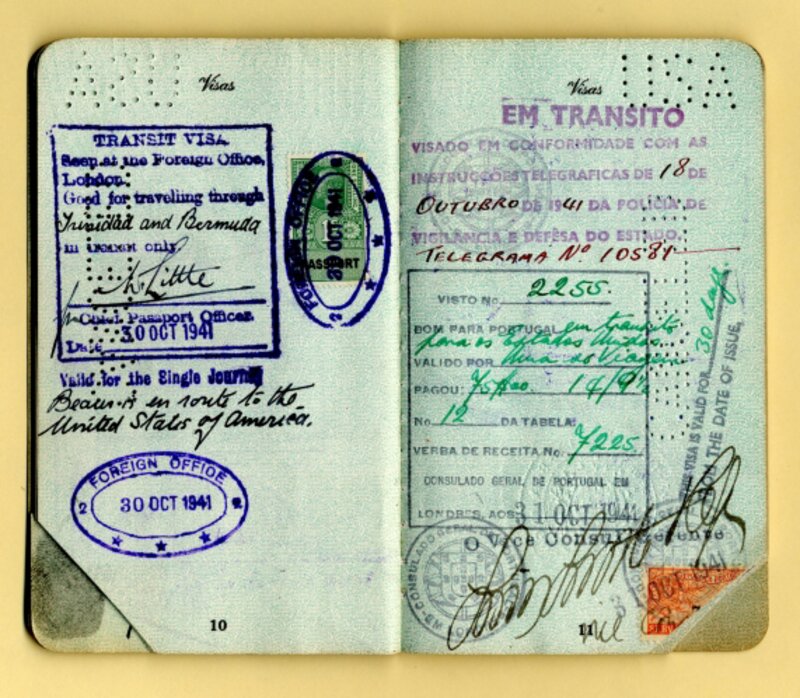

Murrow at CBS, Europe

CBS's European office in the spring of 1937 was a small London office outfit consisting of Murrow, a secretary, and an office boy responsible for organizing radio programs to be broadcasts to the United States via the BBC. Both Murrow and William L. Shirer, hired by CBS for continental Europe in summer of 1937, were increasingly frustrated at being ordered to solely organize cultural broadcasts when Germany, in their opinion, was in fact preparing for war. The Anschluss of Austria in March 1938 became the turning point for Murrow's radio career. For the first time, he himself broadcast the news directly from Vienna, Austria. The New York office liked his voice, his presentation, and his marketability, and gave its approval. From then on, Murrow was also a correspondent. The Anschluss and the ensuing rivalry between NBC and CBS in covering it, also helped Shirer and Murrow to persuade CBS administrators that they had to do more in order to compete with NBC and to cover the situation evolving in Europe. It took the Sudetenland crisis in fall 1938 and Murrow's and Shirer's extensive coverage of it to finally convince CBS of the logic of their argument. It took another ten months for the man in charge of CBS's news operation, director of special events Paul White, to give the permission to hire more staff. Over the next few years, Edward R. Murrow became a household name for the American radio public. Broadcasts by his team of correspondents, the 'Murrow Boys', and his own programs about a war unfolding and enduring for seemingly endless seven years, made Murrow into an icon - fueled by CBS's intense publicity efforts to beat out its competitors. Most of Murrow's broadcasts originated from London. As CBS director for European broadcasts, Murrow usually was forced to stay in the capital or in the UK, from where he coordinated programs and did his daily broadcasts to the U.S. He relied on his correspondents to report from throughout Europe and the various Allied fronts, as well as to feed him information he needed for his own analysis. Rarely did he get a chance to do a radio broadcast from elsewhere, a constraint he detested. There were only a few days of broadcasting from Austria after the Anschluss (March 13-18 1938); a couple of weeks reporting from Tunesia in March 1943; a stint as combat correspondent accompanying British and U.S. bombing flights from England; and reporting from General George Patton's Third Army in Germany, as well as from the concentration camp in Buchenwald in April 1945.

A Day's Work

The pace of work was frantic. The workload often overwhelming. Still, even during moments of crises, broadcasts from across Europe were smoothly orchestrated by Murrow in London. But what aired as seamless and effortless programs in radio sets back in the U. S. belied the tremendous amount of labor that went into setting up those broadcasts technically, topically, and analytically. (For more information on these challenges and censorship restrictions, please go to 'Murrow Boys'). During the Sudetenland crisis in September 1938, a typical day for Murrow ran as follows:

"Murrow participated personally in thirty-five transmissions and arranged or was directly concerned with a total of 151 short-wave programs from other European points. The tempo reached a dizzy pace on September 28, when he began his day at 7:00 A. M. with a personal broadcast. He then put on a monologue from Frank Grandin in Paris, a commentator introduced from the House of Commons, a pickup from Prague, an interpolation by Pierre Bedard of Premier Daladier's speech. Then Murrow connected CBS with Berlin to hear William Shirer, went back to Prague for Vincent Sheean. Presently Murrow introduced the Archbishop of Canterbury, later Stephen King-Hall. He ended his day around 6:00 A.M. London time with final summaries from Paris and Czechoslovakia."3

Paying for that kind of coverage was expensive for American broadcasting companies. For NBC and CBS, the cost of covering the ten days of the Czechoslovakian crisis ran to about $190,000 to pay for "cables, oceanic telephone tolls, speakers' fees, rebates to advertisers for time diverted to news programs" as Scribner's Magazine reported at the time. To put this into perspective: a well paid factory worker in the Midwest earned about $125 a week and the first federal minimum wage was $.25/hour in 1938.

Transporting The Listener - Writing for the Voice

Murrow's broadcasts - their language, content, and style -- were a tribute to his speech instruction at State College of Washington and his intensive training by professor Ida Lou Anderson. A friend who was reading to Ms. Anderson, whose eyesight was waning, recalled:

"Frequently, as I was reading to Ida Lou on Sunday afternoons, I would notice her eye on the clock. I knew that was always a sign that it was approaching the hour when Ed Murrow's voice would come in over her radio with his familiar announcement, "This - is London." From then on, no one was allowed to speak or even move in Ida Lou's dark room; with her eyes closed she became a bundle of concentration as every muscle tensed to listen more intently to each inflection, each tone of the voice of her beloved friend and pupil. Generally her comments at the end of his broadcast would be full of price and nothing but praise, but one in a while she would find some criticism of Mr. Murrow's broadcast and immediately she would want to write him her thought or suggestion. These comments were always valued by Ed Murrow and his replies were filled with gratefulness for her level judgment and her keen comments. She told me one afternoon that Mr. Murrow had urged her to cable him in London a brief message or comment at his expense every week, and that he would include it in his broadcast back to the United States. But Ida Lou, with her great lack of any desire for publicity, wrote her ideas to Mr. Murrow - for his personal use..."

– Ida Lou Anderson, A Memorial, 1941, p.15-16.

It was Anderson who advised Murrow on how to speak his famous phrase 'This is London;' an intonation that many broadcasters still attempt to copy to this day. It was R. T. Clarke, BBC's senior news editor and former military historian and classics scholar, who instructed Murrow on how to adjust a script to the peculiarities of radio broadcasts. Clarke was responsible for BBC news to be 'written for the voice.' BBC scripts were dictated to typists so as to be more informal, direct, and leaner in presentation.4 Murrow adopted this technique that also took care of his spelling difficulties, a weakness that Murrow thought might have been dyslexia. Guided by Clarke's learned discussions of historical events, Murrow began to incorporate larger and historical contexts into his stories. And adapting how the queen and Londoners wished each other 'So long and good luck' during the Blitz of London, turned into Murrow's 'Good Night and Good Luck' signature line of later years.

Murrow's scripts demonstrate what transnational broadcasts were supposed to achieve in his opinion: to transpose the listener to a new location or situation, and to provide analysis and facts for them to make up their minds. A good listener, Murrow encouraged people from all walks of life to talk to him without being self-conscious, and then quoted these soldiers, cab drivers, women, children, or workers. He expertly wove everyday details such as sounds, laughter, smells, change in dress code, or individual worries and woes into his political and economic analyses and put them on the air. He and other correspondents chafed at the rigorously adhered to objectivity standards of American broadcasting, which tended to veer into dangerous appeasement or neutrality on issues where there appeared to be no neutral side. Murrow's solution was to use the common British citizen and his views as an anonymous aggregate to express his own personal analysis and proposals. And Murrow was graceful in acknowledging on the air when he did not know something or when he was speculating so that listeners realized that others besides Murrow were frequently also only speculating or did not know.

London Broadcasts

London Blackout

Talking for the first time about blackouts in London, Murrow stated: “I don't know how you feel about the people who smoke cigarettes, but I like them, particularly at night in London. That small dull, red glow is a very welcome sight. It prevents collisions, makes it unnecessary to heave to, until you locate the exact position of those vague voices in the darkness. One night several years ago I walked bang into a cow, and since then I've had a desire for man and beast to carry running lights on dark nights. They can't do that in London these nights, but the cigarettes are a good substitute.”

London without Children

He reported on the evacuation of London in 1939, of course, mentioned developments in official opinions in London regarding the war, and then went on. "I neglected to tell you one thing about London. As a matter of fact, this particular aspect of the war didn't hit me with full force until this afternoon -- Saturday afternoon over here. It's dull in London now that the children are gone. For six days I've not heard a child's voice. And that's a strange feeling. No youngster shouting their way home from school. And that's the way it is in most of Europe's big cities now. One needs the eloquence of the ancients to convey the full meaning of it. There just aren't any more children."

Women's Wear and London at Night

Most of his reports concern official statements, political developments, and news of the war, but he would also include tidbits about daily life, e.g. that tailor-shop windows were now filled with uniforms and new women's wear, “a sort of coverall arrangement with zippers and a hood – one piece affairs, easy to put on. They are to be worn when the sirens sound. So they are called appropriately enough siren suits.” He talked about how the streets and monuments looked different under a state of war noting that London on a wet Sunday afternoon in wartime resembled London on a wet Sunday afternoon in peace time. “The real changes come at night to London. Then it is a city of sound, generally slow, cautious sound – what it really looks like at night I can't tell you because I never have been able to see more of it than has been disclosed by the beams of my puny flashlight.”

Conversation - A Casualty of War

He spoke about what people read, what people invented now that the war had started. Murrow noted that, contrary to dear British custom, people did not talk about weather any longer since public weather information had become a censored item. And ..."that's the sort of thing that doesn't crop up in the course of man-made conversation in London. Something has happened to conversation in London. There isn't much of it. You meet a friend, exchange guesses about the latest diplomatic move, inquire about a mutual friend who has been called up, and then fall silent. Nothing seems important, not even the weather. ... Wit, happiness, manners, and conversation sink gradually. Conservation is about to become a casualty."

No Poet, No Popular Song, No Hate

On December 11, 1939, Murrow observed: “Sometimes, while reading long articles, listening to speeches, asking questions of so-called experts, one gets the strange feeling that perhaps no one really understands at all – that the machinery is out of control, that we are all passengers on an express train traveling at high speed through a dark tunnel toward an unknown destiny. We sit and talk as convincingly as we can, speaking words someone else has used. The suspicion recurs that the train may have no engineer, no one who can handle it – no one who can bring us to a standstill. Maybe that's why more people seem to be reading their Bibles these days [he mentions elsewhere, however, that church services are less frequented at the same time]. Perhaps that's why this war has not produced a poet or a really popular song, why it hasn't even produced much hatred.”

Broadcasts from Afar

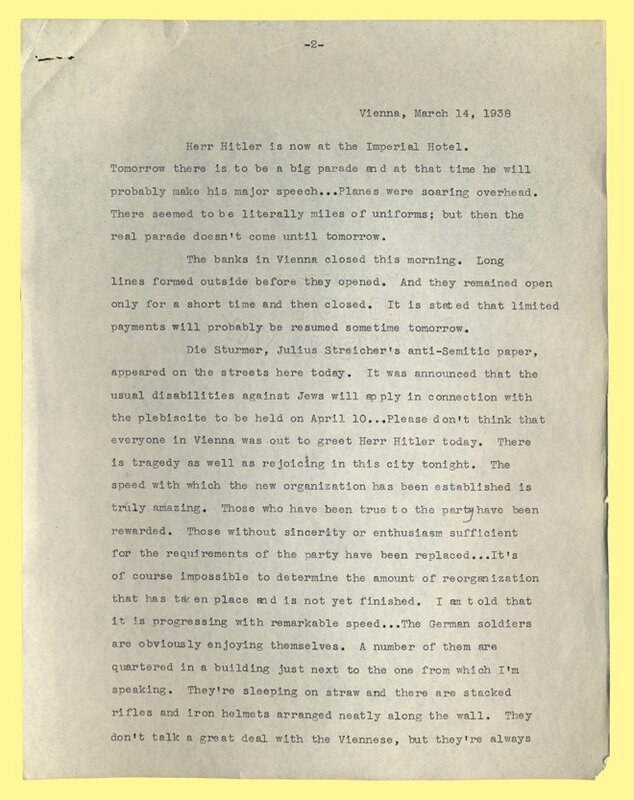

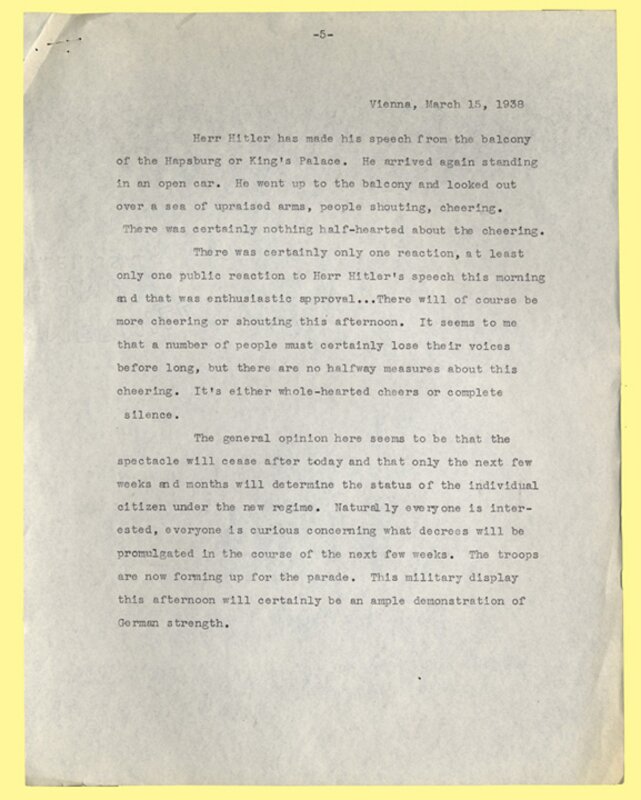

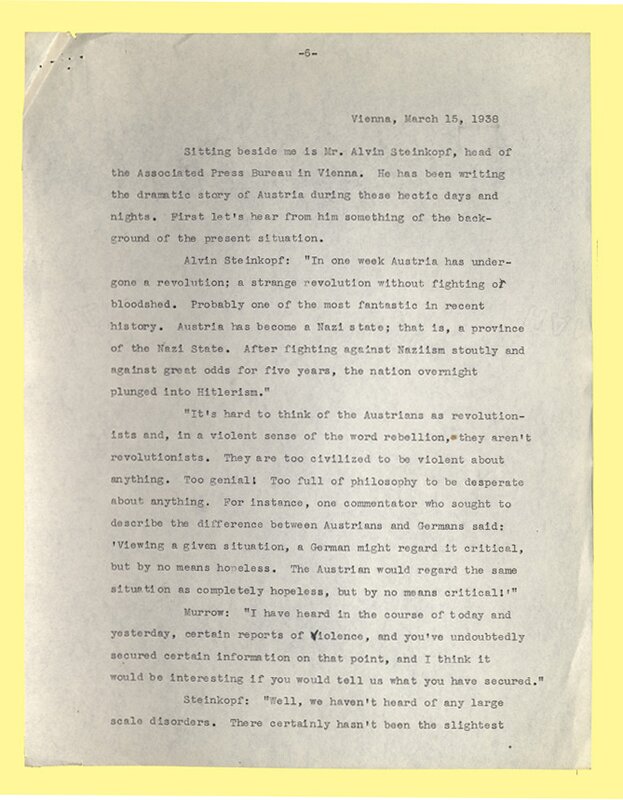

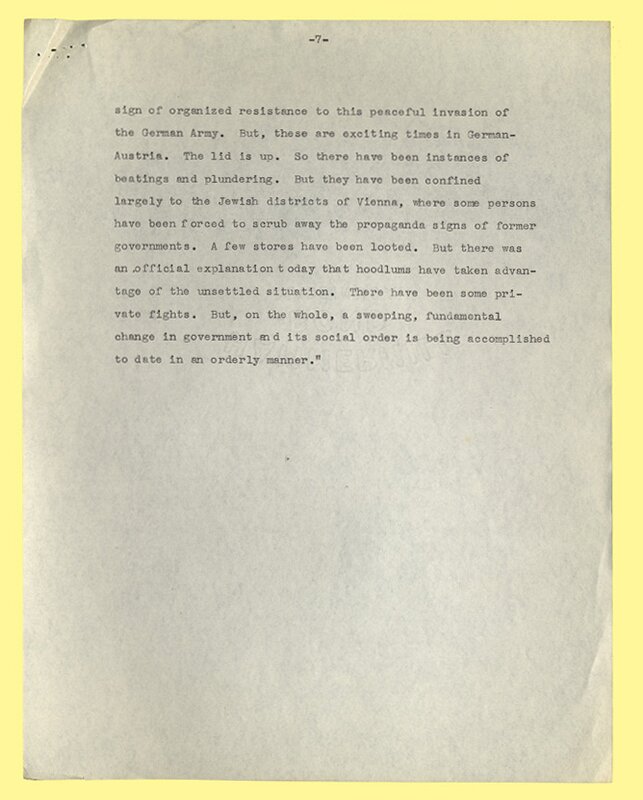

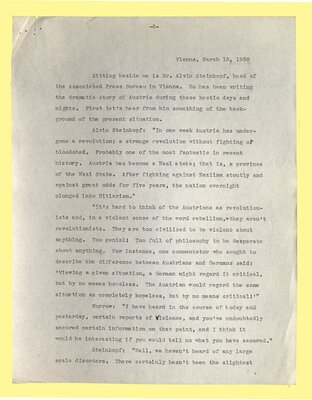

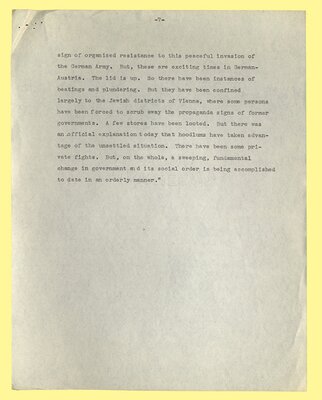

His second and third broadcast from Vienna, Austria, on March 14 and 15, 1938, show Murrow at the beginning of what was to become his famous manner of reporting. When you read the script, do not forget that German censors might rather cramp a correspondent’s style.

Murrow courted danger. He was frustrated at being stuck in London and, instead, wanted to report on bomb attacks and developments on the front but he rarely got the opportunity to do so.

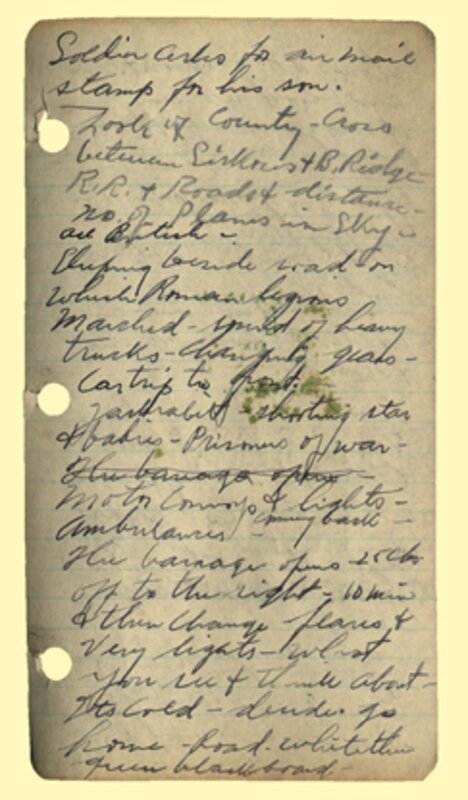

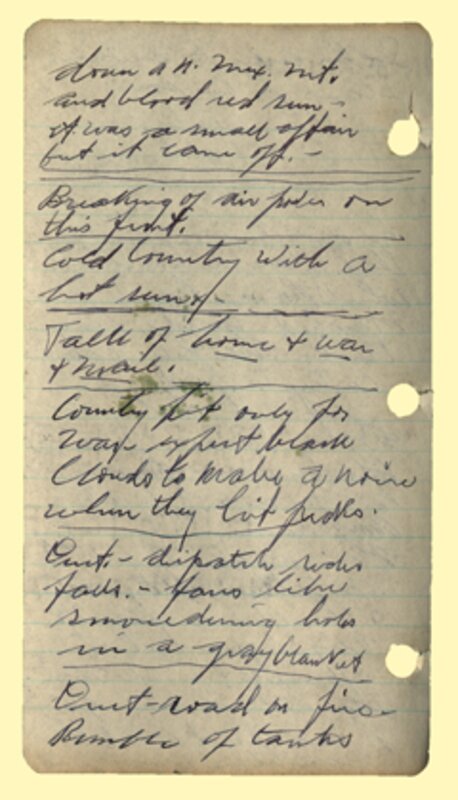

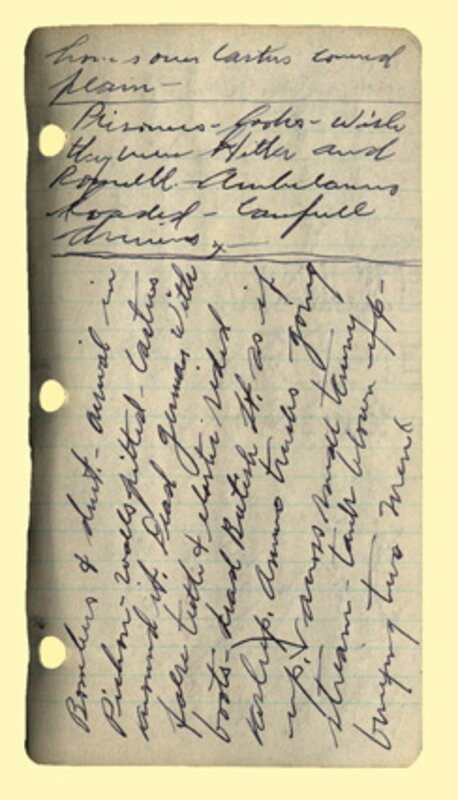

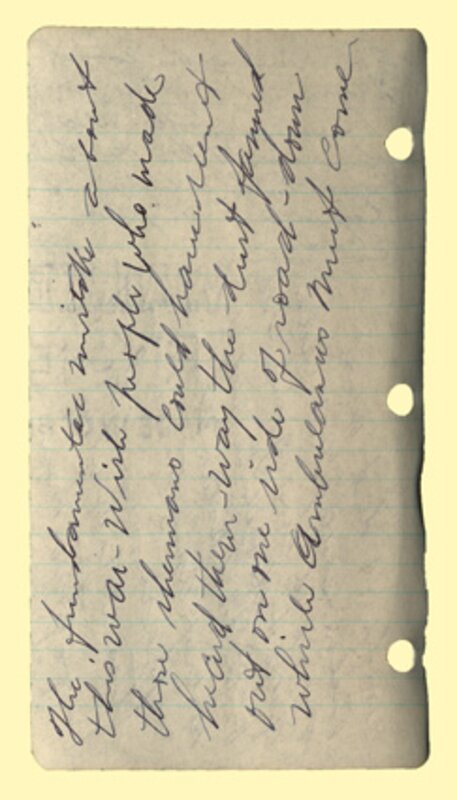

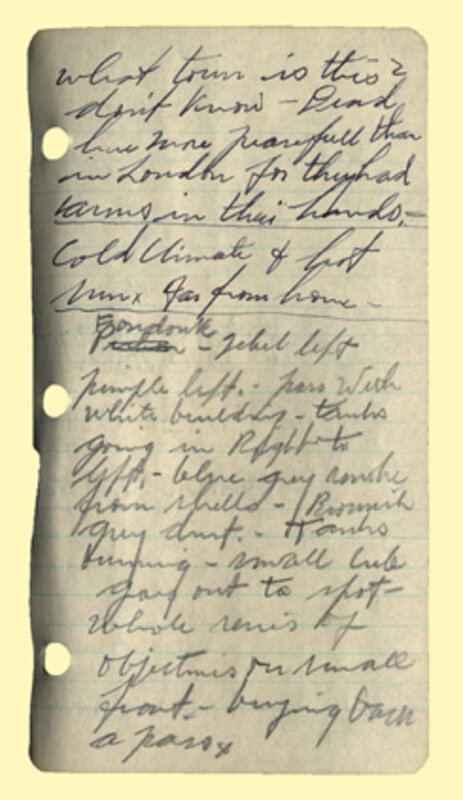

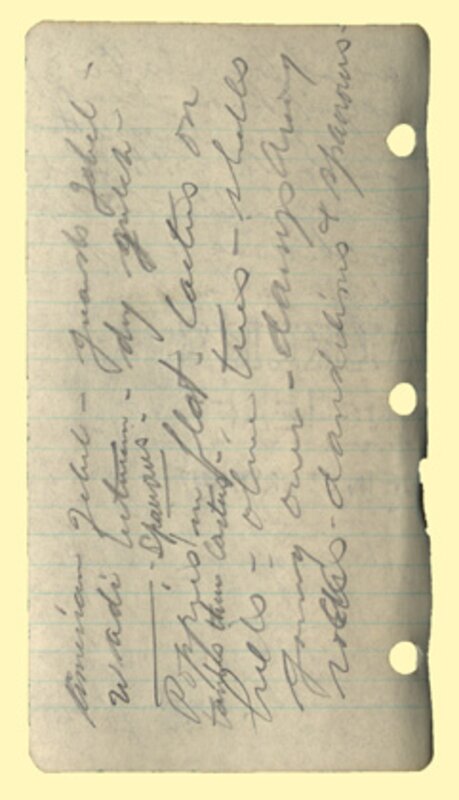

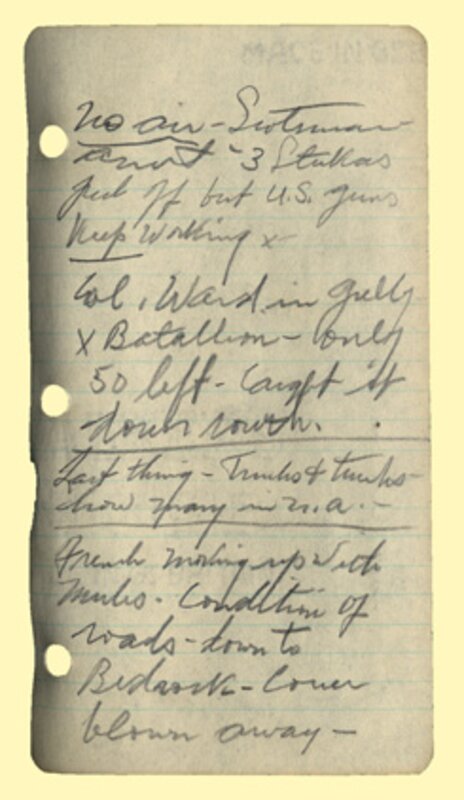

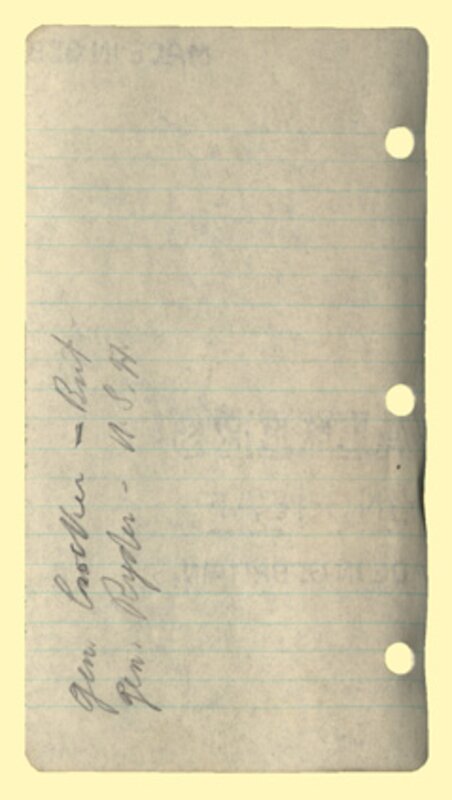

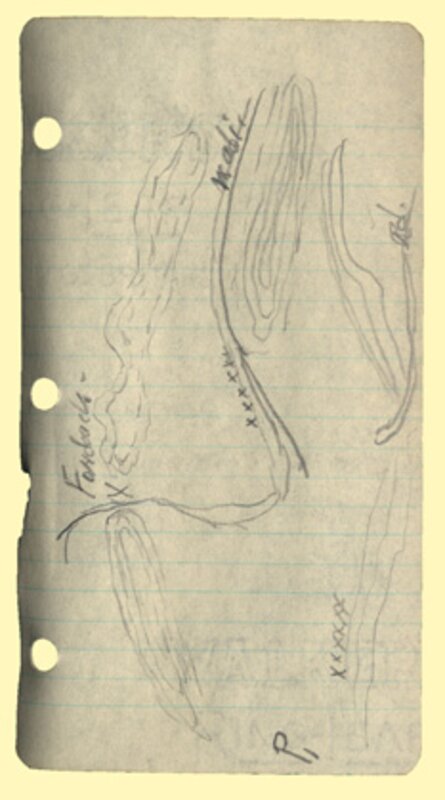

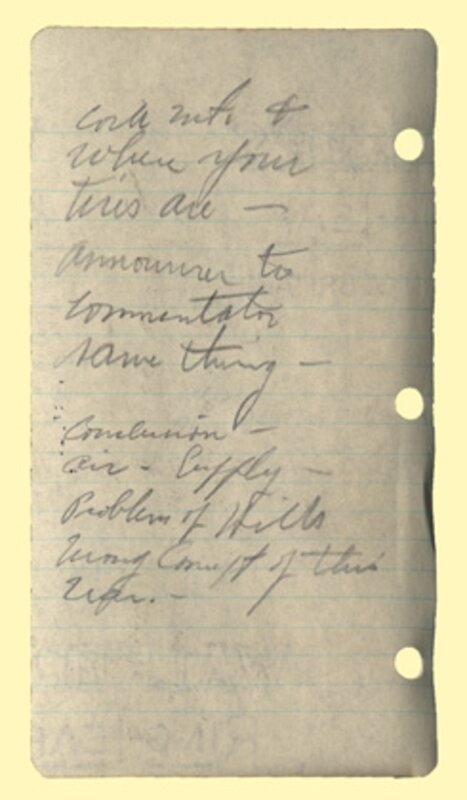

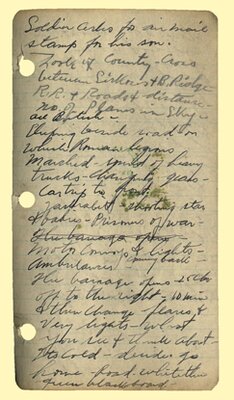

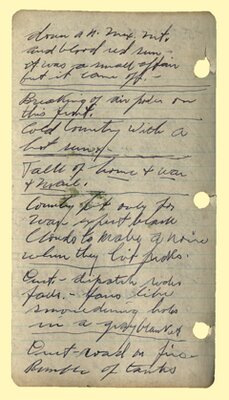

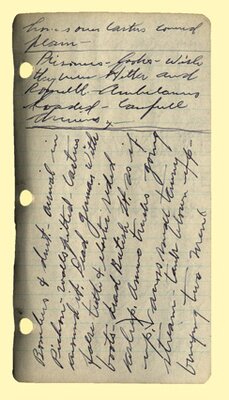

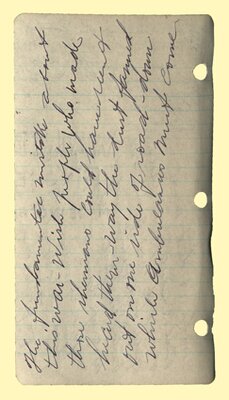

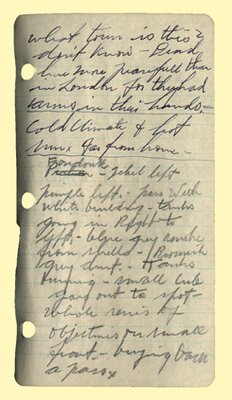

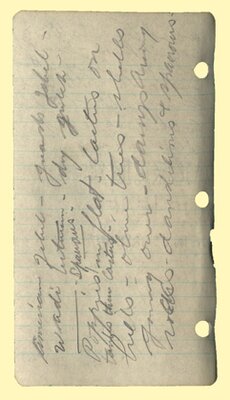

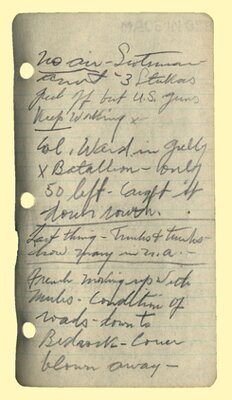

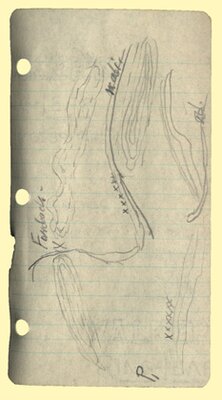

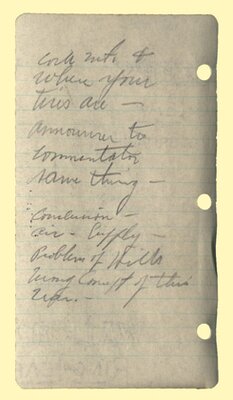

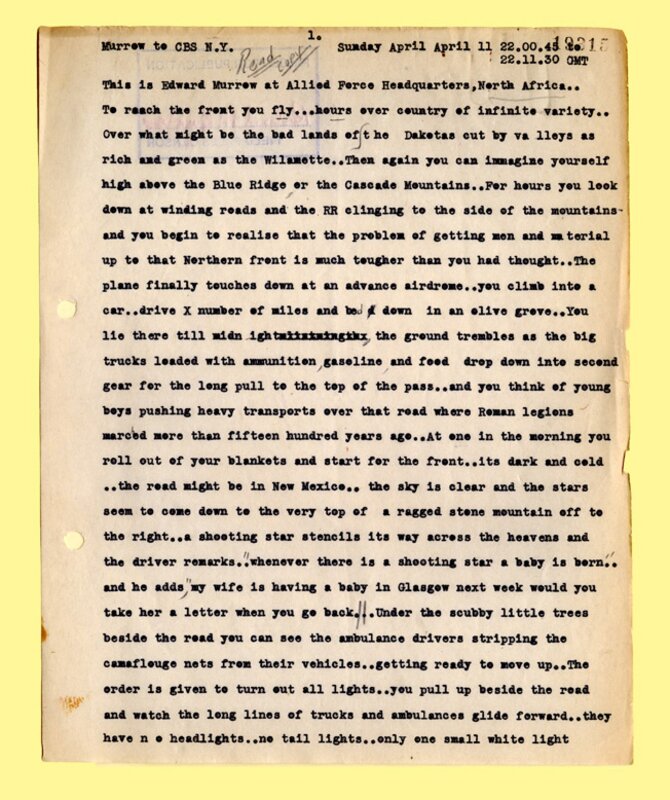

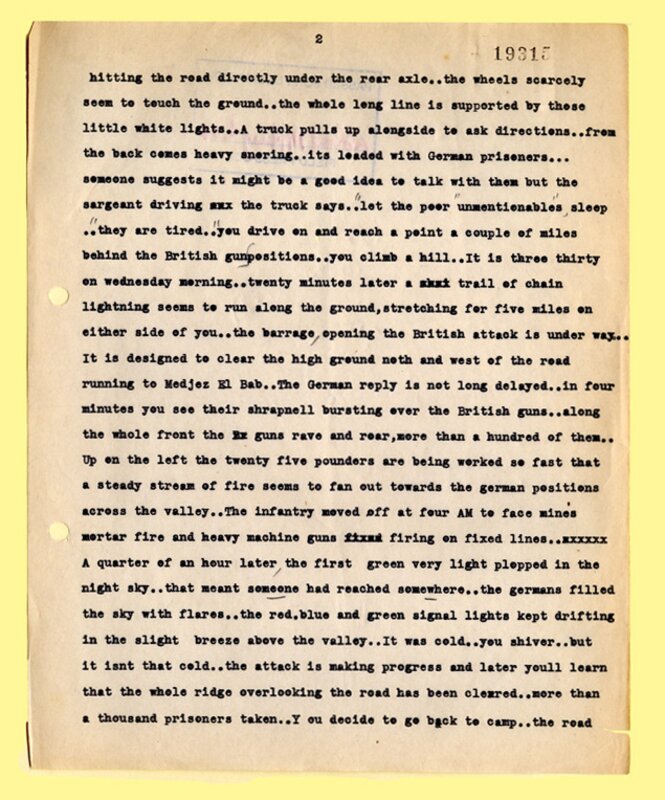

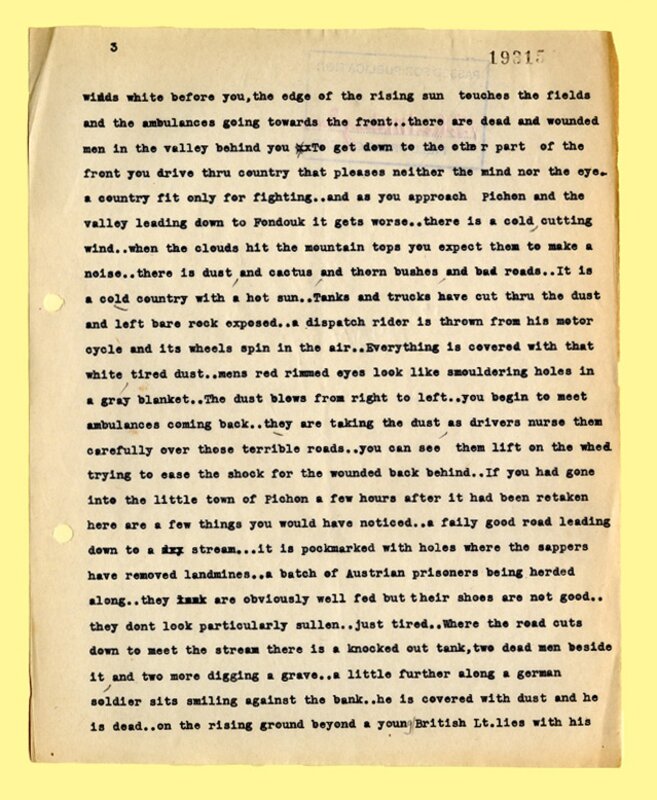

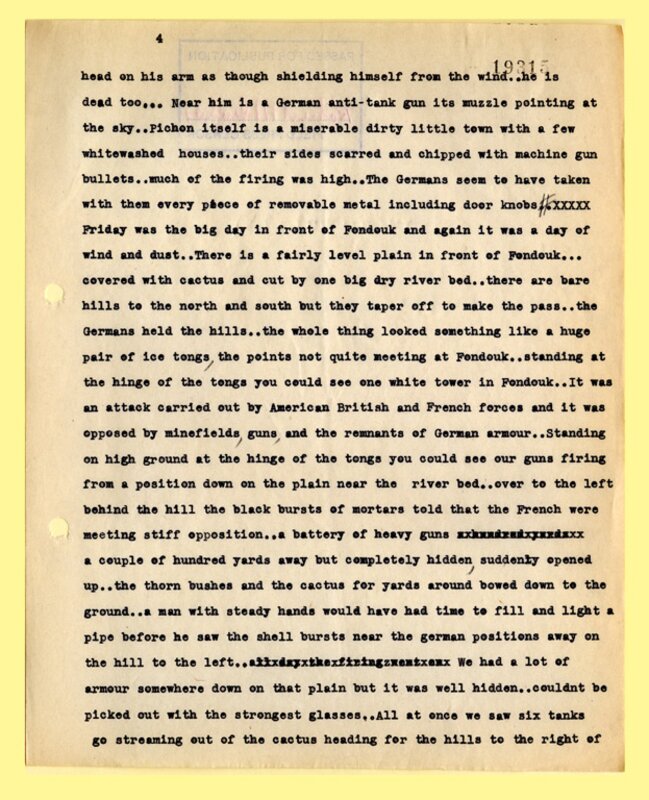

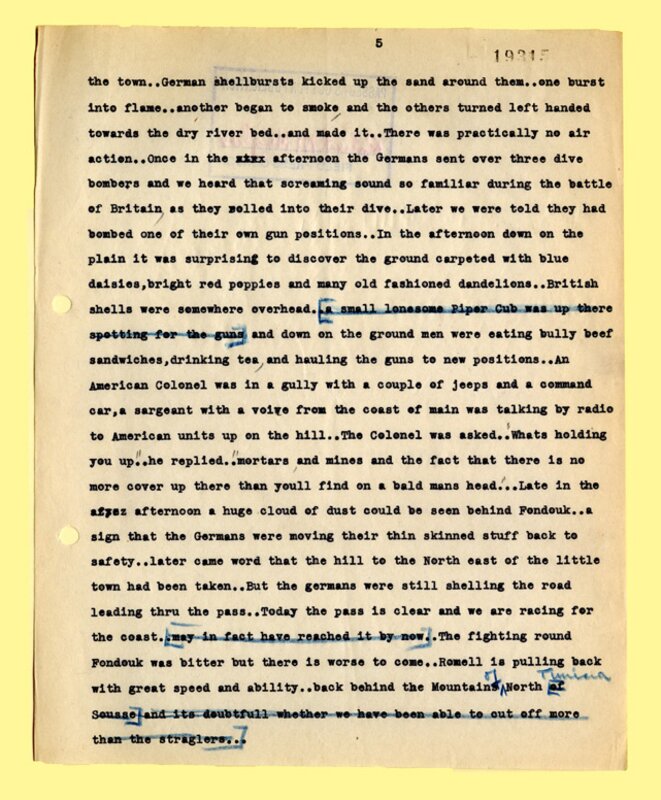

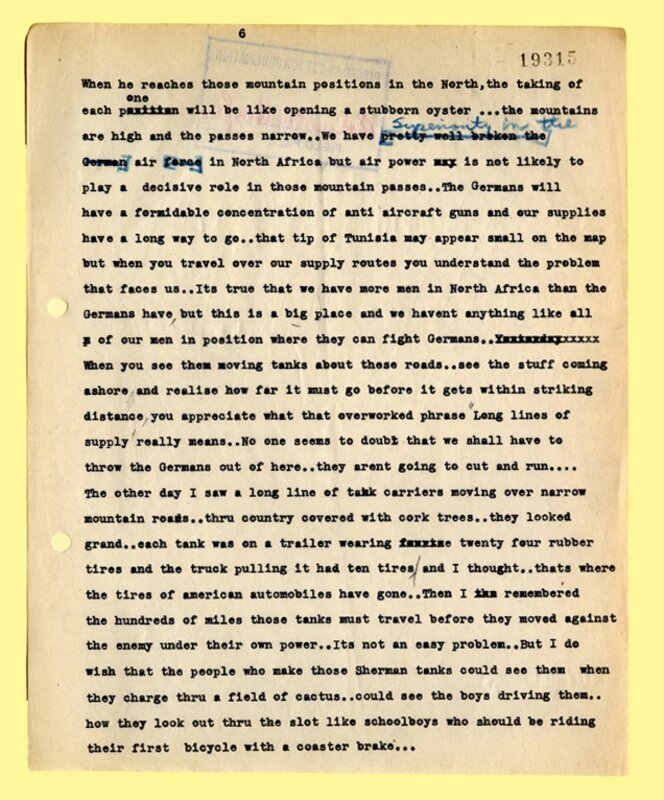

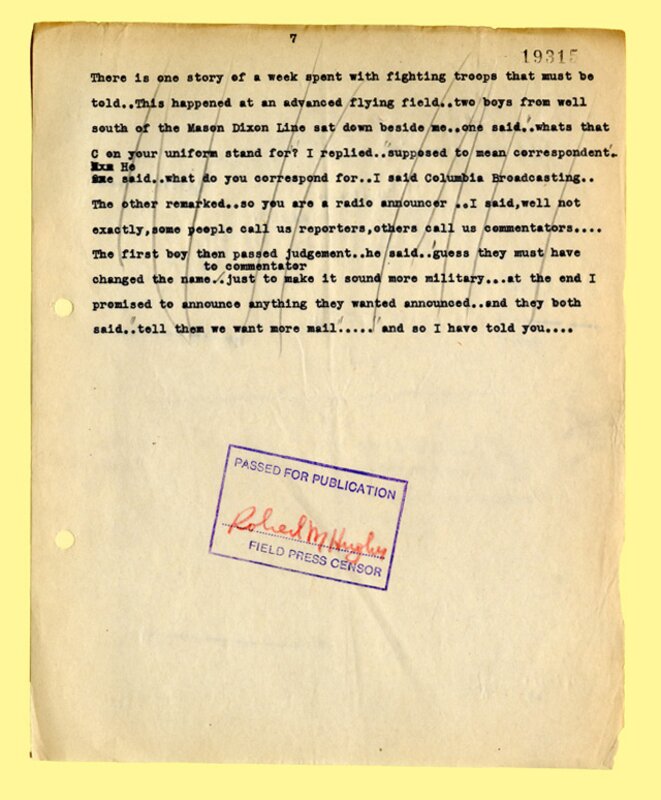

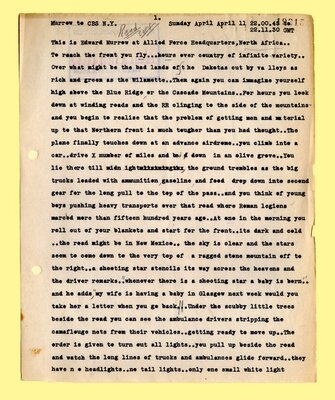

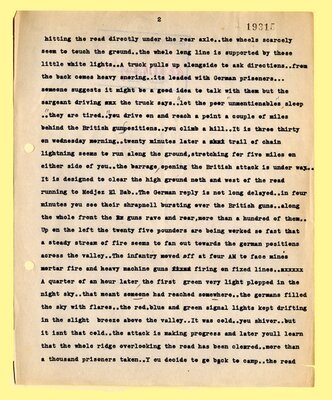

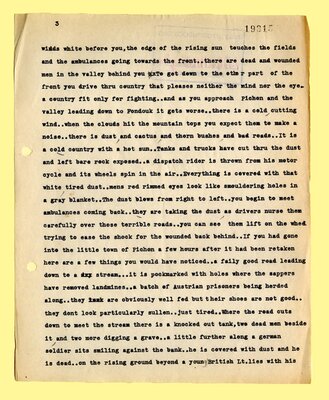

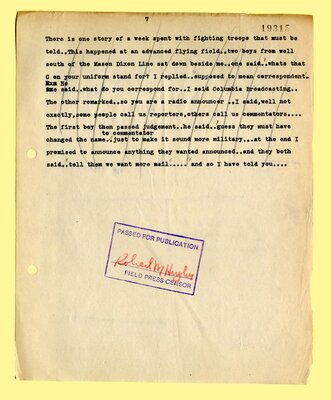

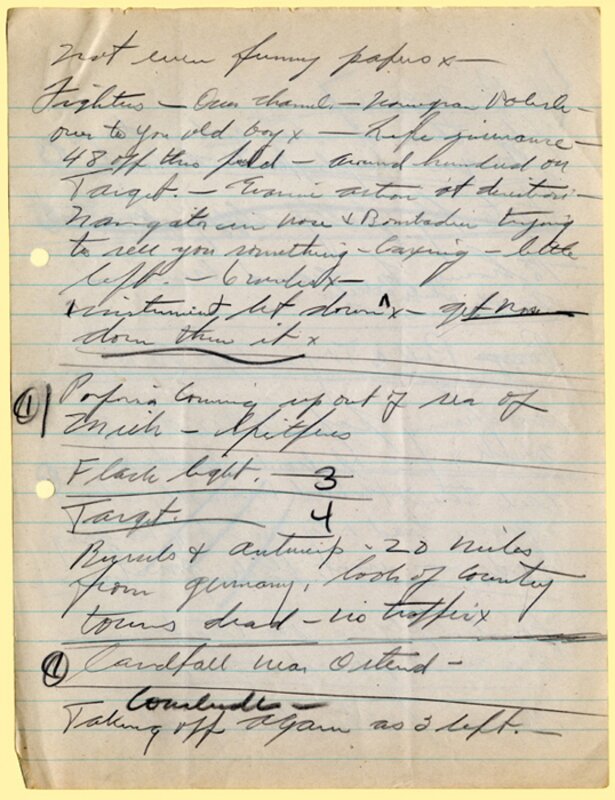

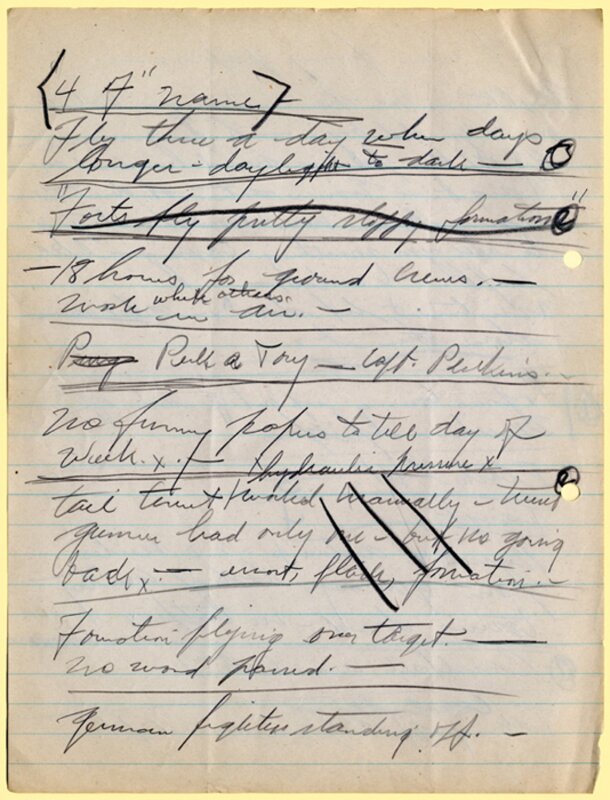

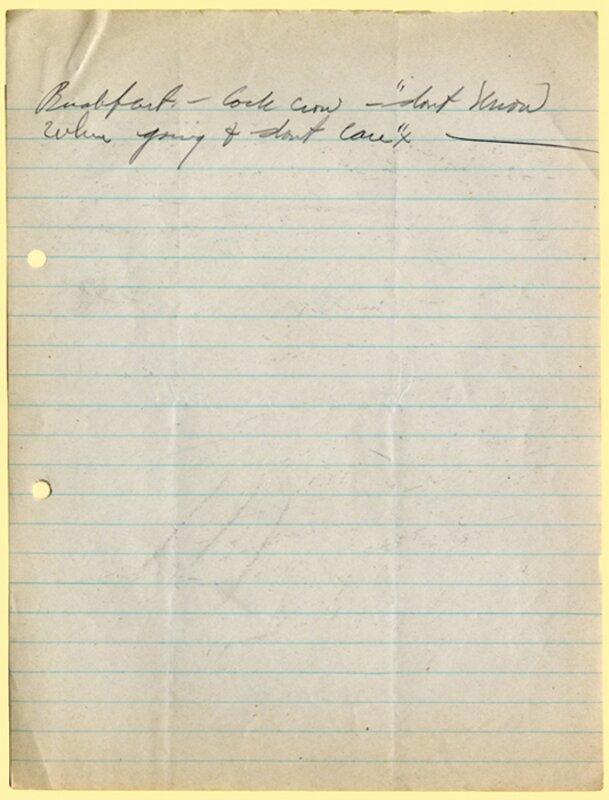

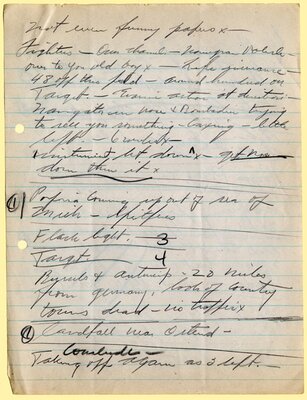

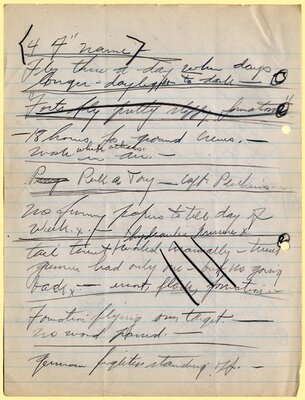

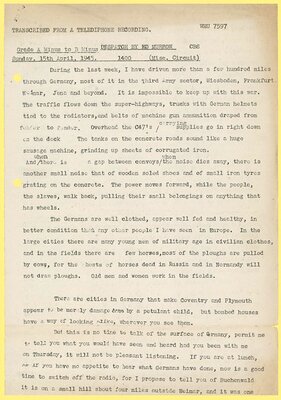

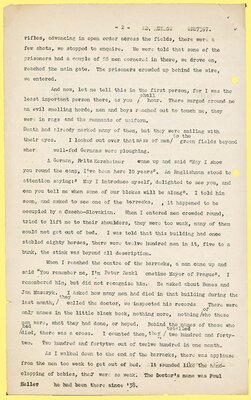

Above, are field notes he took while accompanying the British attack towards Pichen and the valley leading down to Fondouk, both Tunesia, North Africa in late March and early April of 1943. Below, is a broadcast Murrow wrote based on these field notes. Murrow's polished style when he reported from London turns frayed and disjointed, mirroring the reality of life at the front and of reporting about combat. And yet, the broadcast shows all the elements for which he had become famous.

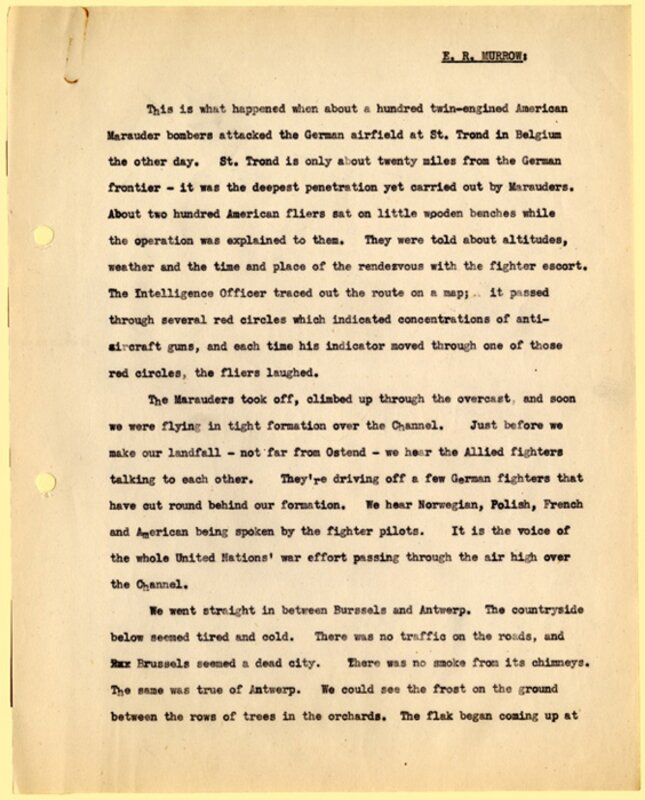

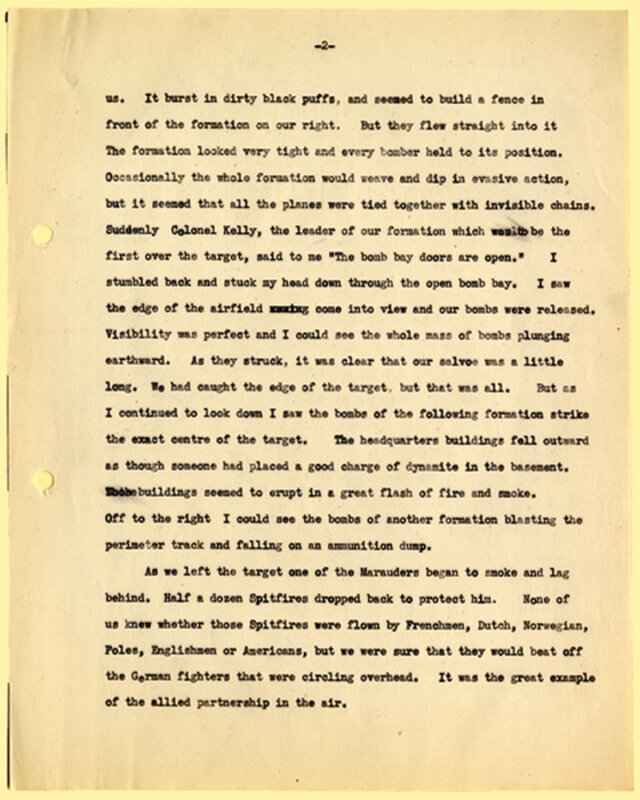

Broadcasts from London differ in style and quiet demeanor. This holds true even when Murrow reports about Marauder bombers attacking a German airfield at St. Trond, Belgium, an attack he witnessed and took notes about at the front. He later described the attack from the BBC station in London in late February 1944.

Not that life in London was easy and safe. Murrow's office was bombed four times and numerous colleagues and friends were injured and killed in bomb attacks throughout the city.

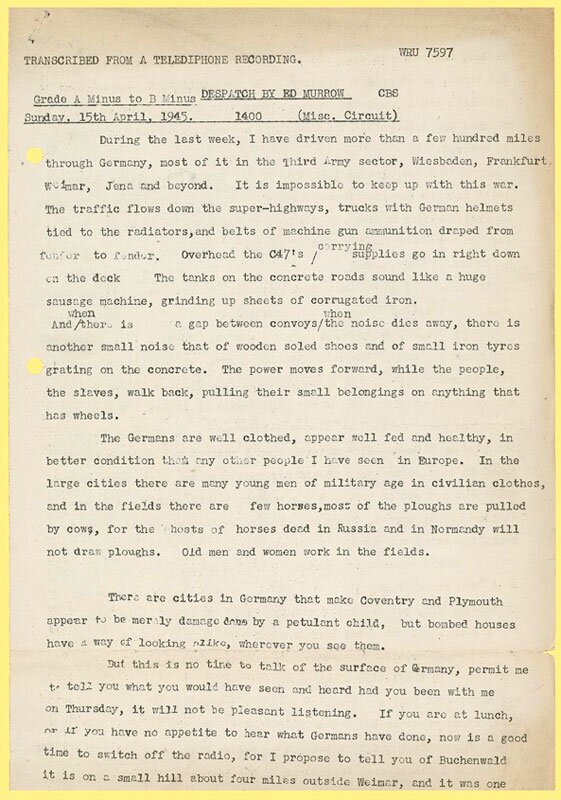

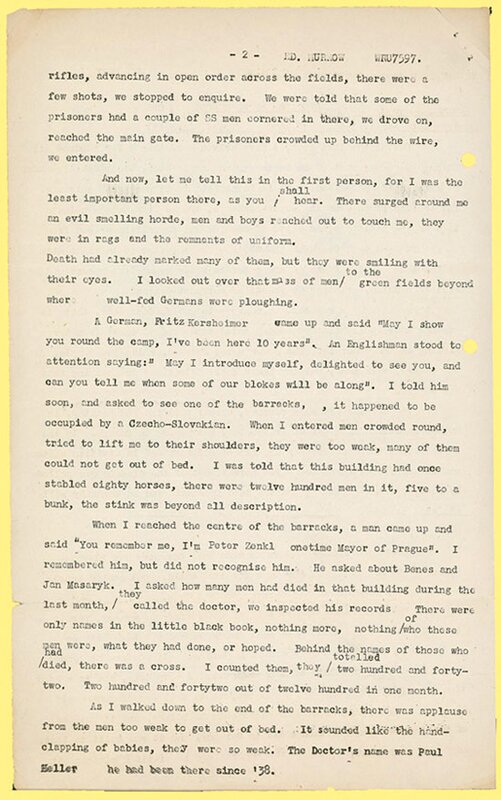

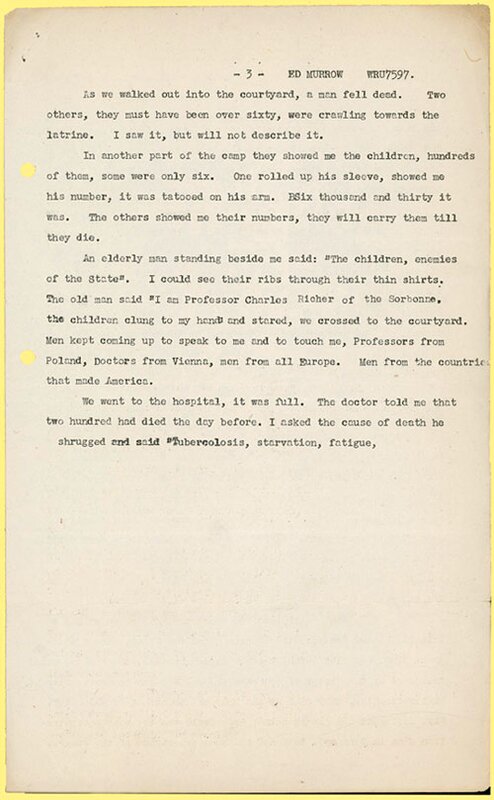

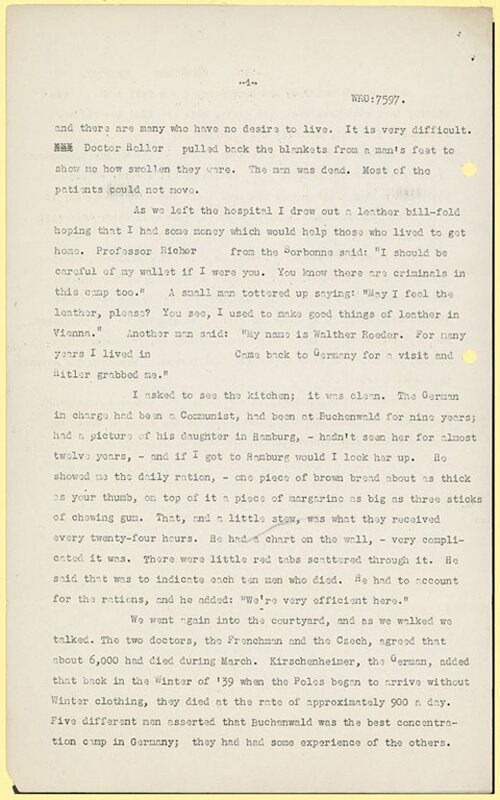

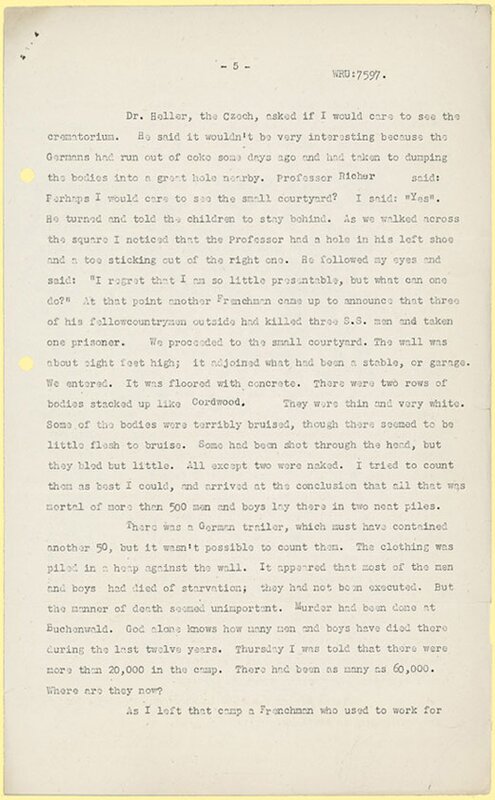

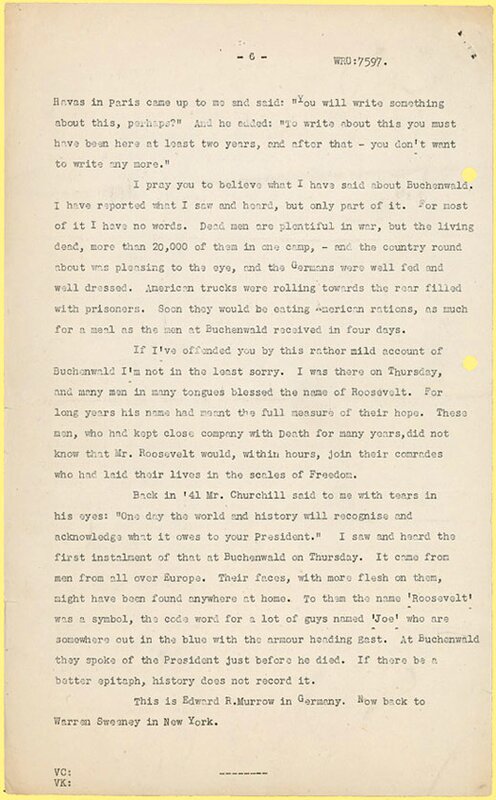

Telediphoned to CBS, London, on April 15 1945, Murrow's Buchenwald broadcast was less dire and less overwhelming than other concentration camp broadcasts. And perhaps, it became more famous precisely because of this, and because of the fame of its author. More palliative and less shocking, Murrow's text was widely covered in the press. It was translated, reprinted, or re-broadcast repeatedly in Germany and England, for instance.

Throughout the war, Murrow and a few of his 'Boys' had reported about discrimination against Jews and about concentration or extermination camps. However, these broadcasts had been exceedingly rare. Nor did their broadcasts offer any analysis or opinion about what an appropriate allied response might be and this is in marked contrast to other topics about which Murrow and others offered cogent analysis and criticism.5 In this, Murrow and CBS were like most other correspondents and networks.

1) Max Jordan took part "in the first-ever simultaneous multiple-remote-pickup broadcast, a stunt which brought together an array of European broadcasting officials in separate airplanes over the Atlantic coast." In: Max Jordan -- NBC's Forgotten Pioneer, by Elizabeth McLeod, http://www.midcoast.com/~lizmcl/jordan.html. (Note: URL is non-functional as of 6/5/2018)

3) Landry, Robert J., "Edward R. Murrow," Scribner's Magazine, vol. 104, no. 6, Dec. 1938.

5) The field notes to Murrow's Buchenwald broadcast are in the Edward R. Murrow and Janet Brewster Murrow Papers, Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections.

Credits

Text and Selection of Illustration

Susanne Belovari, PhD, M.S., M.A., Archivist for Reference and Collections, DCA (now TARC)

Digitization

Michelle Romero, M.A., Murrow Digitization Project Archivist

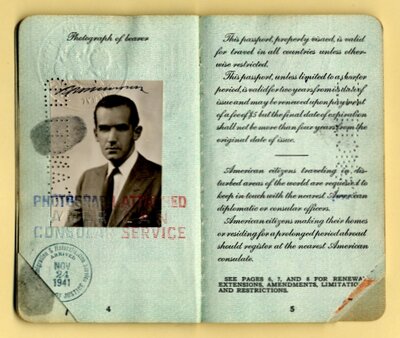

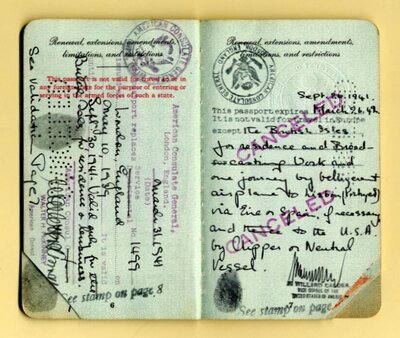

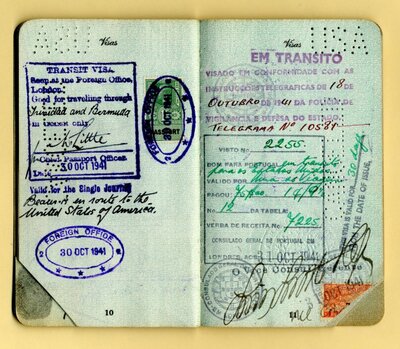

Images

All images: Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, TARC, Tufts University, used with permission of copyright holder, and Joseph E. Persico Papers, TARC.

Partial Bibliography

For a full bibliography please see the exhibit bibliography section.

Books consulted include Persico (1988) and Sperber (1986); also Kendrick (1969).

The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, TARC, especially Murrow's scripts and Murrow Broadcast from London about the campaign in North Africa, April 25, 1943; also Joseph E. Persico Papers and Edward Bliss Jr. Papers both at TARC.

Ida Lou Anderson: A Memorial (The State College of Washington: 1941). This book contains a short biographical note about Ms. Anderson and memories by family members and students including Murrow's. Murrow also contributed financially to its printing. The Edward R. Murrow Room, Tufts University, contains three copies of the book.

In Search of Light: The Broadcasts of Edward R. Murrow 1938-1961. Introduction and edited by Bliss, Edward Jr. (Alfred A. Knopf: New York 1967).

Briggs (all volumes).

BBC Year Book 1943 (Jarrold & Sons, LTD., Norwich & London).

Times Magazine article on Raymond Gram Swing as the news analyst in the U.S. in 1939/1940, FIND, January 8 1940, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,763171,00.html accessed March 1, 2008. See also: http://www.coutant.org/swing.html

Hyde Ed. "Edward R. Murrow - WWII's Greatest Front Line Newsman," Bluebook Bonus, July 1965, p. 23-80.

Landry, Robert J. "Edward R. Murrow," Scribner's Magazine, vol. 104, no. 6, Dec. 1938.

McLeod, Elizabeth. Max Jordan -- NBC's Forgotten Pioneer, http://www.midcoast.com/~lizmcl/jordan.html

Murrow, Edward R. "Transatlantic Broadcasting, 1st December 1942 first proofs," BBC Year Book, in: The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, TARC.

Burton, Paulu. British Broadcasting: Radio and Television in the United Kingdom (University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 1956).