Murrow Boys

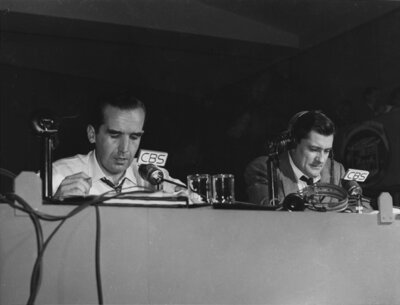

The 'Murrow Boys' - a group of foreign correspondents during World War II

Sixteen years after the first transatlantic radio broadcast in 1926, radio listeners...

"have come to expect of transatlantic broadcasting something more than stunting or transatlantic trickery. They expect to hear not only the news and the speeches of statesmen. They expect to hear the authentic accent of their allies. They want to hear not only the news but the political, social, and economic climate in which it is made. Transatlantic broadcasting is becoming more and more of a job of transportation. Transporting the individual listener from his home in Maine or Idaho by saying to him: 'Look, if you were over here this is what you'd find. This is the sort of thing you would hear, see, and smell. The kind of food you would eat; the people you would meet; the books you would read, and all the rest."

– Murrow, Transatlantic Broadcasting, 1st proof, Dec. 10, 1942

This is as close to a professional credo as one is likely to get for the 'Murrow Boys.' It is a committment that Edward R. Murrow shared with his team of foreign correspondents. And it is what they did quite brilliantly.

Core to the endeavor was a group later identified as the 'Murrow Boys' and which included one woman, Mary Marvin Breckinridge. They were a small number of erudite correspondents that Murrow, based in London, assembled before and during the war. Most came to be close family friends and remained professional colleagues throughout Murrow's life. While many might later claim membership, Murrow himself appears to have viewed only eleven individuals to be part of his special wartime group.¹ These were Mary Marvin Breckinridge, Cecil Brown, Winston Burdett, Charles Collingwood, William Downs, Thomas Grandin, Richard C. Hottelet, Larry LeSueur, Eric Sevareid, William L. Shirer, and Howard K. Smith.

Hiring the 'Boys'

With their news broadcasts about the invasion of Austria in spring 1938 and about the Czech Crisis in fall of that same year, Edward R. Murrow and William L. Shirer had been able to persuade CBS that their task was to make news broadcasts and not to organize cultural broadcasts. This was a marked deviation of CBS radio news policy which had had no news correspondents up to that point. But it mirrored a news tradition already in effect at BBC, where Murrow's broadcasting office was located. When CBS's director of news, Paul White finally agreed to increase CBS news team in Europe in July 1939, Murrow and others began to hire more staff - among them the later Murrow Boys.

• William L. Shirer - hired in August 1937, working from Berlin, Vienna, and Geneva

• Thomas Grandin - hired spring 1939 to cover Paris

• Larry LeSueur - hired late in the summer of 1939 to cover Rheims, France

• Eric Sevareid - hired in the summer of 1939 to cover Paris

• Mary Marvin Breckinridge - hired in fall 1939 covering Northern Europe

• Cecil Brown - hired February 1940 to cover Italy

• Winston Burdett - hired by Betty Wason in spring 1940 to replace Wason and to cover Scandinavia

• Howard K. Smith - hired in spring of 1941

• Charles Collingwood - hired in the winter 1941 to replace Eric Sevareid in Paris

• William Downs - hired in September 1942 to cover Moscow

• Richard C. Hottelet - the last of the Murrow Boys, hired in 1944 to cover the invasion of Normandy

These correspondents first covered the war in Europe crisscrossing the continent for their reporting (e.g. Mary Marvin Breckinridge, Tom Grandin, Eric Sevareid, or William Shirer), then they moved on to North Africa (e.g. Cecil Brown), Iran and Iraq (e.g. Winston Burdett), and Asia (e.g. Eric Sevareid).

It is not a coincidence that the Murrow Boys were largely men. CBS administrators back in New York, and in particular Edward Klauber, did not want women correspondents. In fact, Klauber even insisted on having only male secretaries in his offices in New York. It is why Breckinridge eventually left to get married, as Janet Brewster Murrow mentioned in one of her letters at the time. It is why Betty Wason, who had covered Scandinavia and done courageous and outstanding broadcasts about the invasion of Norway as a stringer, was asked to find a male colleague to replace her. She hired and trained Winston Burdett. It is why Charles Collingwood was given a chance -- Klauber had refused Murrow's first choice, Helen Kirkpatrick (1908-1997). Kirkpatrick had already proven herself as an outstanding European and war correspondent for the Chicago Daily News. In fact, she had founded Whitehall News with Victor Gordon-Lennox and Graham Hutton. After CBS decided against employing her, she worked for various outfits and ended up as the first correspondent assigned to the headquarters of the native Free French forces operating inside France.

An Adventurous Bent

When selecting correspondents, Murrow was not necessarily interested in them having experience in radio or even journalism. He favored analytical skills, subject and foreign language knowledge, their connections, their writing skills, or their adventurous bent, all of which would serve them well during the dangerous years to come. He repeatedly contradicted CBS administrators in the U.S. who were appalled at the lack of radio presence or voice of many of his candidates, and Murrow was proven right in his choices. Eric Sevareid, for example, might not have had a good radio voice but he wrote thoughtfully, analytically, and beautifully. His broadcasts could be pieces of literature that he might pen in a few minutes or mere hours. Substituting for Murrow in the winter of 1944/45, for example, Sevareid wrote the following moving broadcast about war.

"This is what the war is like, this Sunday afternoon. That is, that's what all those called correspondents or commentators, analysts or observers, will be saying it's like. They believe it, the listeners and readers understand it, and what we say is true enough - but only within our terms of reference, in the unreal language of standard signs and symbols that you and I must use. To the soldier, that isn't what the war was like at all. He knows the real story; he feels it sharply, but he couldn't tell it to you, himself. If I plucked one from his foxhole now and put this microphone before him, he would only stammer and say something like this: "Well, uh, I was lying there, and uh, I saw this Jerry coming at me with a bayonet, and uh, well…; That's how most of them would talk. I know because I've tried them. If the soldier can't tell you what happened to his stomach at the moment, what went on in his beating heart, why the German's belt buckle looked as big as a shining shield - if he can't tell you, no onlooker ever can. …Only the soldier really lives the war. The journalist does not. He may share the soldier's outward life and dangers, but he cannot share his inner life because the same moral compulsion does not bear upon him. The observer knows he has alternatives of action; the soldier knows he has none. It is the mere knowing which makes the difference. Their worlds are very far apart, for one is free, the other a slave. This war must be seen to be believed, but it must be lived to be understood. We can tell you only of events, of what men do. We cannot really tell you how or why they do it. We can see, and tell you, that this war is brutalizing some among your sons and yet ennobling others. We can tell you very little more.

War happens inside a man. It happens to one man alone. It can never be communicated. That is the tragedy - and perhaps the blessing. A thousand ghastly wounds are really only one. A million martyred lives leave an empty place at only one family table. That is why, at bottom, people can let wars happen, and that is why nations survive them and carry on. And, I am sorry to say, that is also why in a certain sense you and your sons from the war will be forever strangers…"– Eric Sevareid, Not So Wild A Dream (1946), p. 493-495. The book is part of Murrow's book collection.

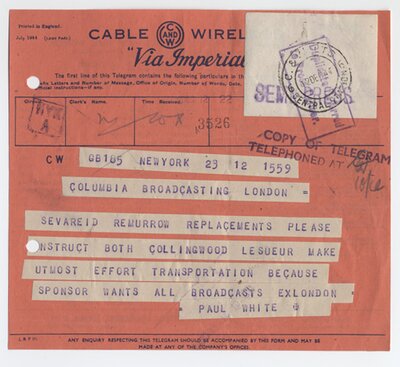

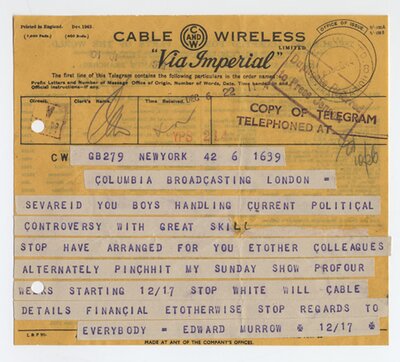

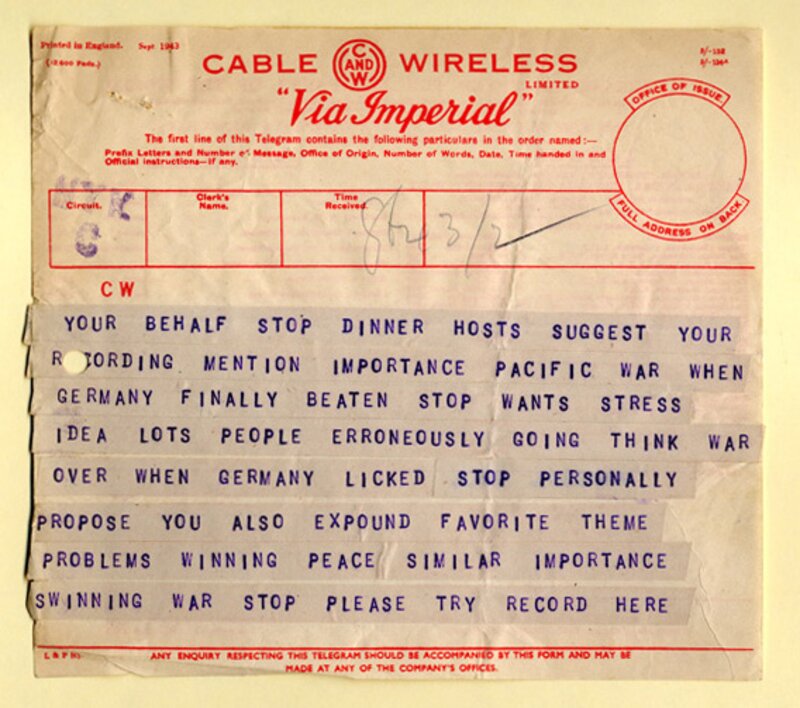

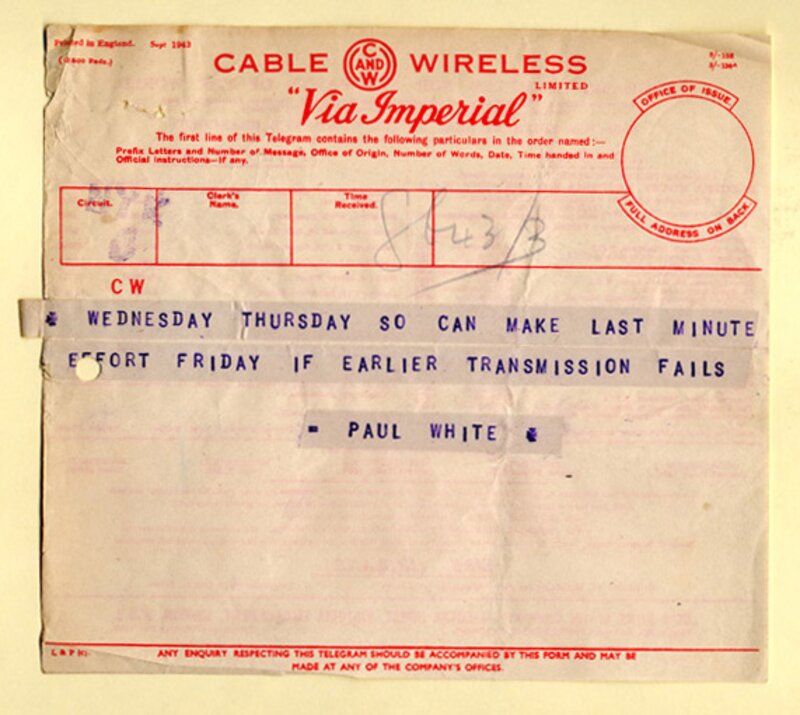

With rare exceptions correspondents selected their own stories. They often broadcasted from outdoor, makeshift radio studios and, for the longest time, they were not allowed to use recordings. The only instructions correspondents might receive would be a terse telegram scheduling a broadcast at its precise time: e.g. 12:50:10 to 12:54:40. The acceptable margin of error was usually 10 seconds. Given imprecise clocks and hostile countries, the inability to hear each other over the ether, frequent relays of broadcasts across third and forth nations or even continents, atmospheric interferences, power outages, marginal (and portable) transmitting facilities, but interestingly enough no enemy jamming of air waves, it seems a miracle that any broadcast actually was heard in the U.S. Many, indeed, were not picked up along the transatlantic route. After the first international CBS news roundup about the Anschluss of Austria on March 13, 1938 - organized by William L Shirer in London within 8 hours with input from Murrow in Vienna, Austria - the organizational feat of bringing together technology, people, and censors did not become less daunting. But it became imaginable and quickly turned into the norm for CBS and others.

Mary Marvin Breckinridge (1905-2002) was a friend of Murrow's from NSFA years; she had been the first NSFA president. Her broadcasts were special due to their content and the angles she took to tell a story. It was her academic background in French, German, Italian, and modern history, her documentary film experience producing the Nursing Frontier Service (1930), her articles as well as skills as photographer traveling in Africa and elsewhere that produced such broadcasts as Ice in Holland in January 1940:

"Attacks over the ice were unsuccessful when tried by the Russians in the last war and again in this one in Finland, because of lack of cover and because artillery fire from either side has a devastating effect in breaking the ice under the advancing army. Now the Dutch are controlling their unique defenses by sending soldiers to break up the ice and by moving the water from one section to another of the water barrier by windmill and pump and thus leaving cracks sic feet wide, and great blocks of upturned slanting ice, most difficult to cross. They say that none of the ice will support tanks, except in the marshy country of North Brabant, where it will pack hard and make a better roadbed than the soft, shallow marsh water. Last week a newsreel was released showing whole battalions of water-barrier troops drilling on ice-skates. This is not new, for when the Spaniards attacked them on foot about three hundred years ago, slipping on the ice in their heavy armor, the Dutch had a good laugh first, and then came up on skates and easily defeated them."

– January 15, 1940 Radio Broadcast number 9, 'Ice in Holland'.

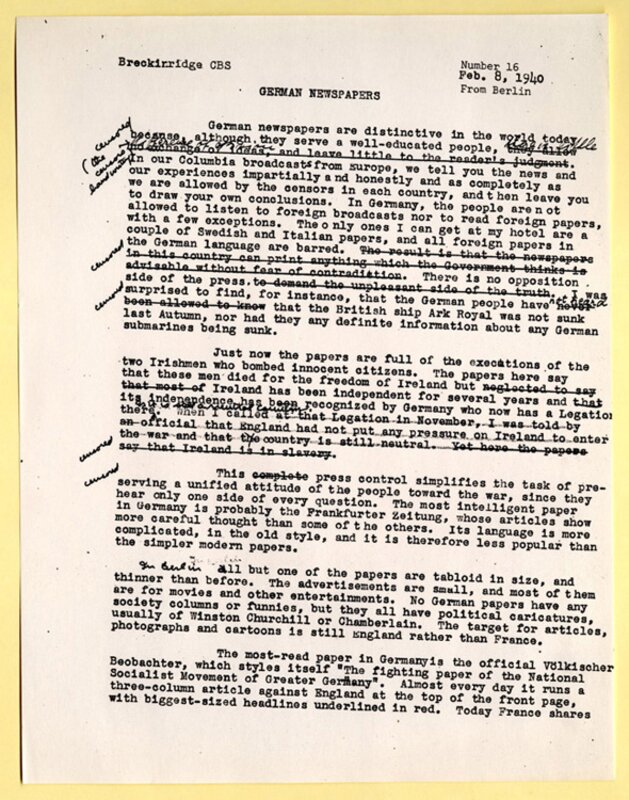

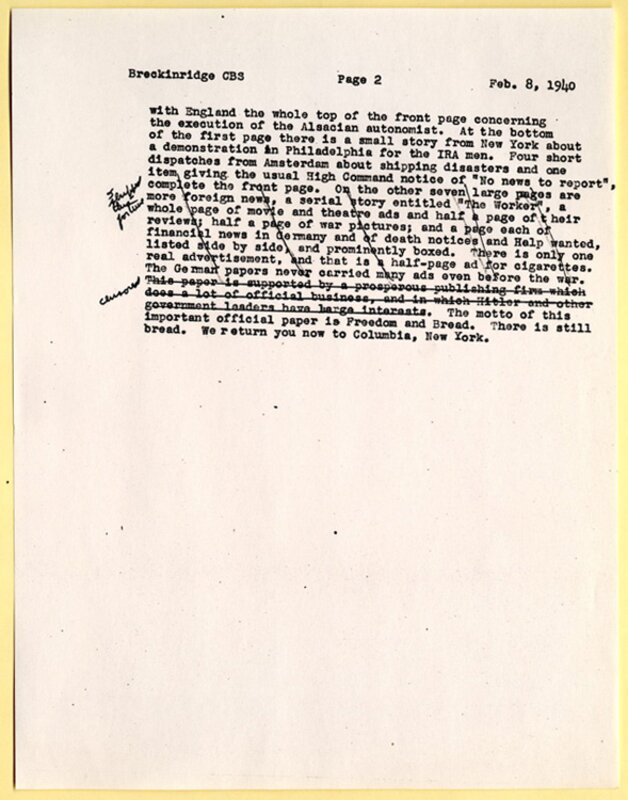

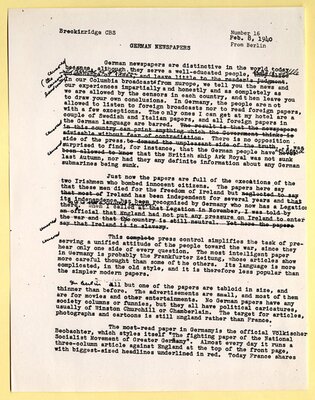

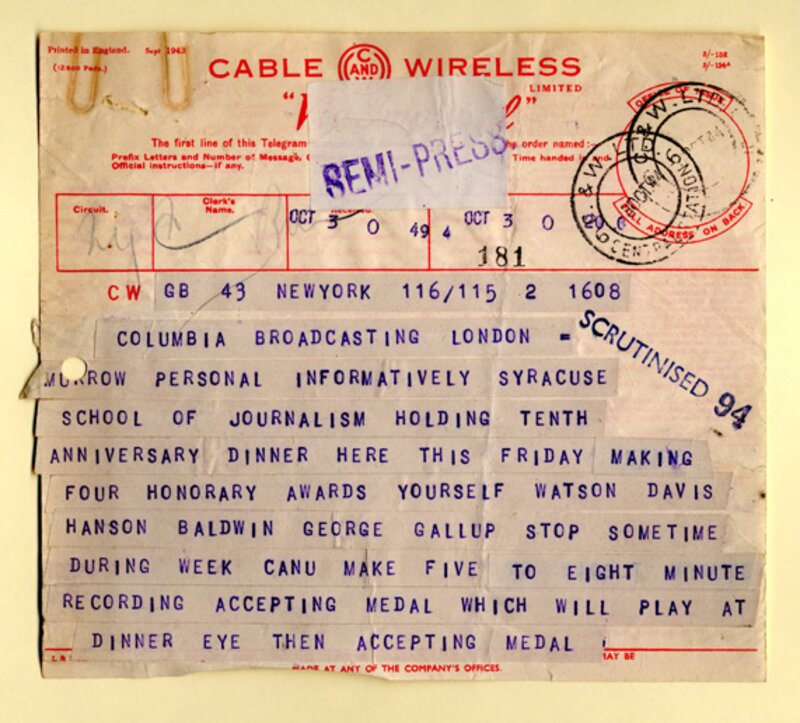

Or take her broadcast titled German Newspapers, a broadcast she did from Berlin on February 8, 1940, while she covered for a vacationing William Shirer. Her photocopy not only shows the telling strokes of the German censor but her skill in evading those censors.

Censorship and Danger

As all other correspondents, Breckinridge and others including Murrow himself, had to adjust their scripts to pass censorship, whether they worked in England or elsewhere. Depending on the language skills of their censors and their own skill as writers, they were able to get out more or less of a story. Breckinridge admired Shirer, who adeptly forged sentences to pass the strict censors in Germany, e.g. when writing about Hitler's birthday: "A crowd of about 65 persons was massed outside the Chancellery."

Breckinridge herself was masterful, however. Reporting about the Voelkische Beobachter, the official and most widely read newspaper of the National Socialist Movement in early 1940, the censors struck out one of her sentences about Hitler's and other's financial investment in the newspaper. But the censors left her last phrase uncorrected: "The motto of this important official paper is Freedom and Bread. There is still bread."² In Germany, usually three but sometimes four censors - from the Foreign Office, the Propaganda Ministry, the Military and an additional one for a story on the women's movement - had to approve and stamp each script while "a technician sat at another [table] with a copy of my script and his finger on a button to cut me off if I departed from it in any way" as Breckinridge told decades later.

Even if correspondents managed to get their stories out and aired, listening to a foreign radio station such as CBS or BBC could be life threatening to German citizens and those from occupied countries. Shirer noted several such examples in his diary:

"February 4th 1940 … In Germany it is a serious penal offence to listen to a foreign radio station. The other day the mother of a German airman received word from the Luftwaffe that her son was missing and must be presumed dead. A couple of days later the BBC in London, which broadcasts weekly a list of German prisoners, announced that her son had been captured. Next day she received eight letters from friends and acquaintances telling her that they had heard her son was safe as prisoner in England. Then the story takes a nasty turn. The mother denounced all eight to the police for listening to an English broadcast, and they were arrested. (When I tried to recount this story on the radio, the Nazi censor cut it out on the ground that American listeners would not understand the heroism of the woman in denouncing her eight friends!)"

– Shirer (1940), p288. The book is part of Murrow's book collection.

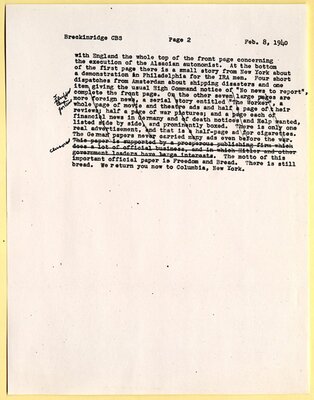

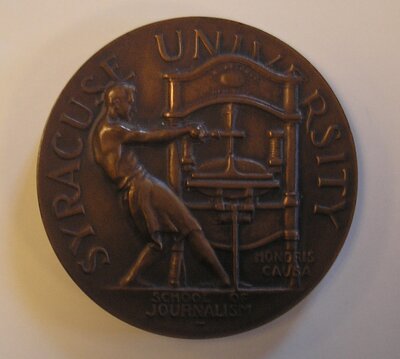

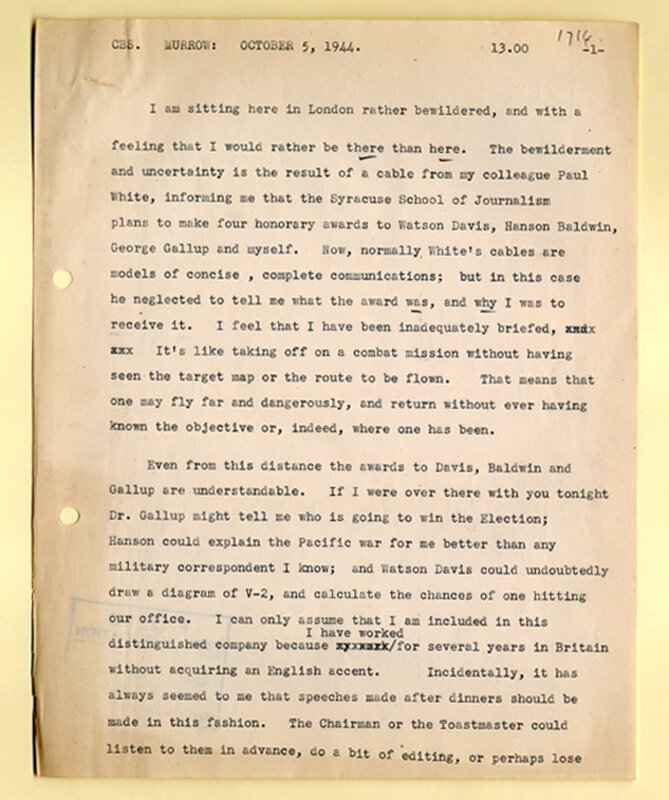

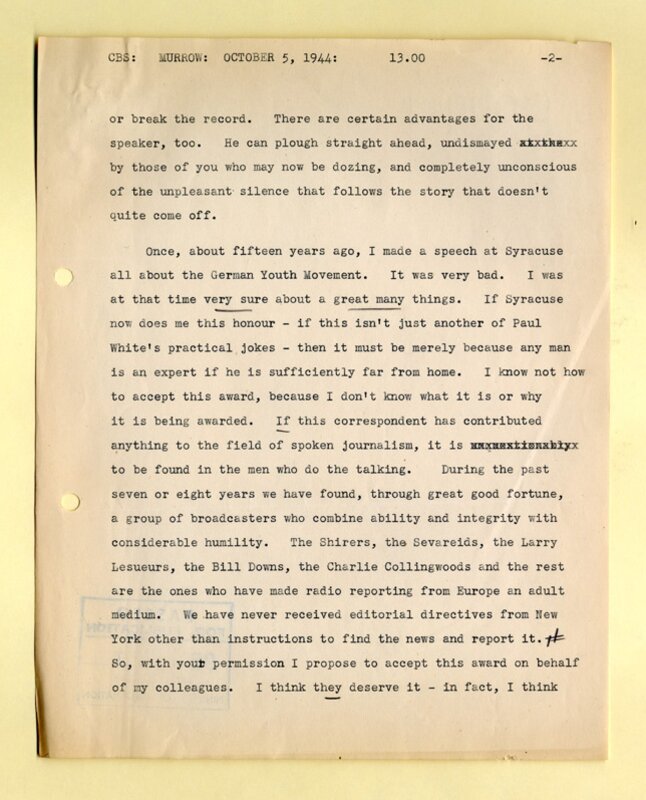

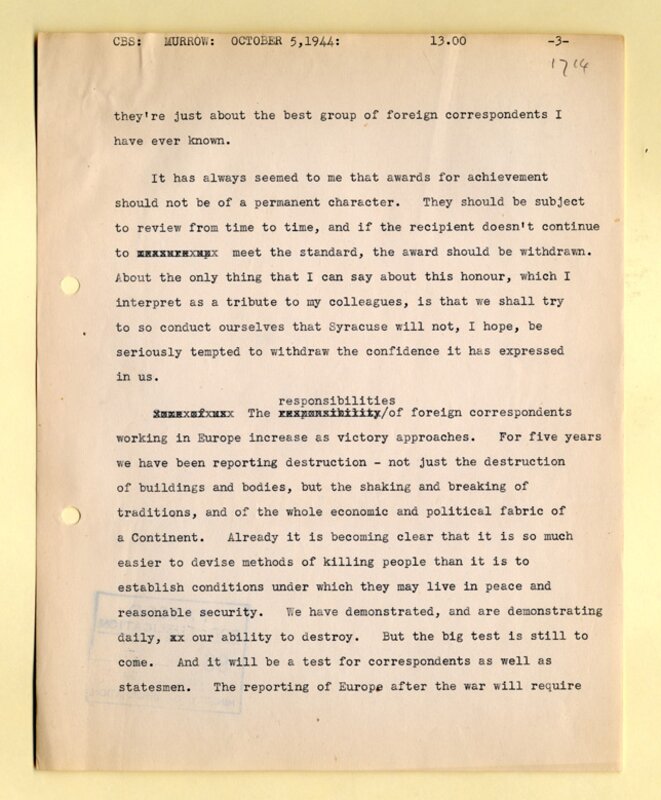

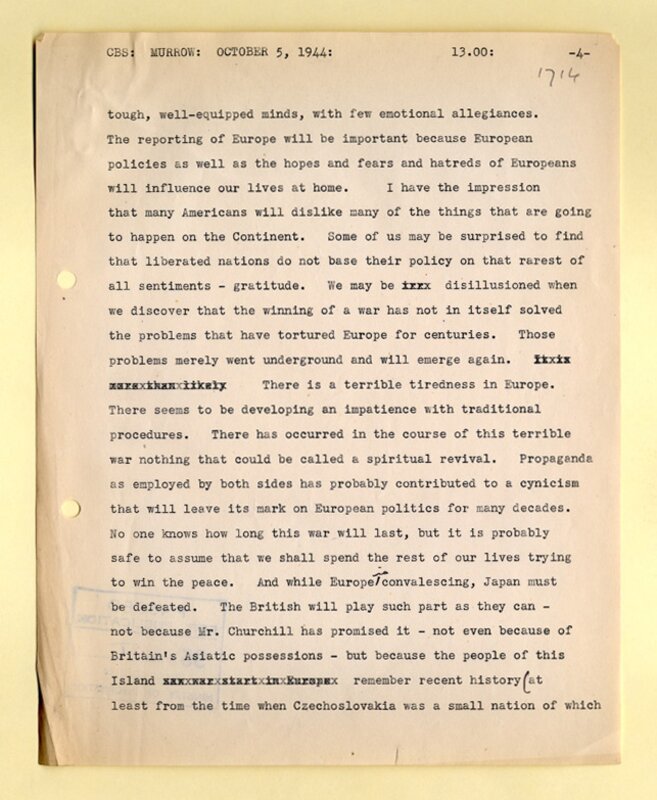

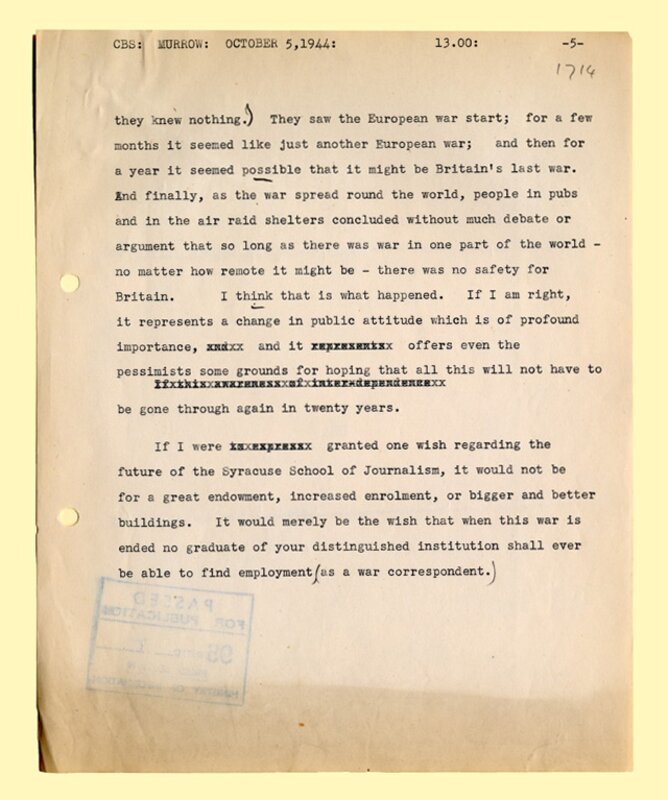

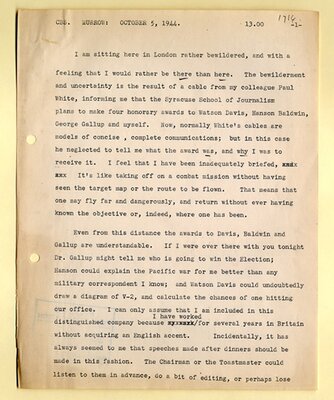

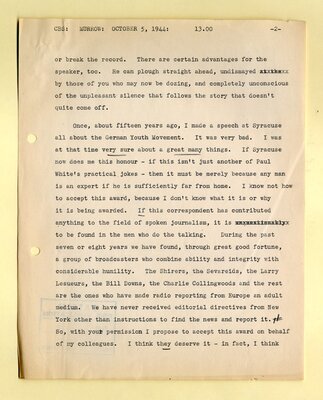

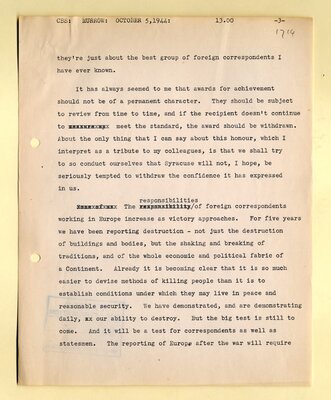

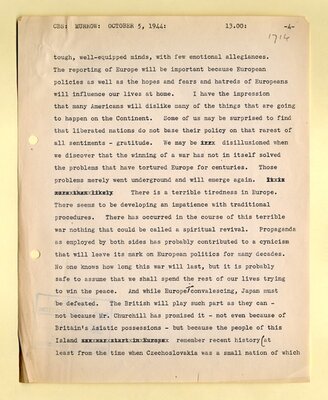

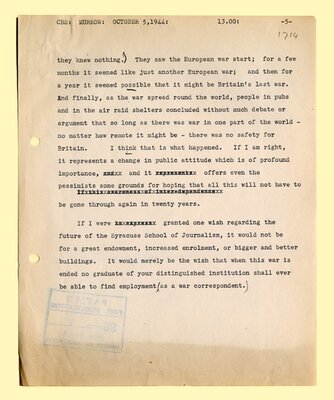

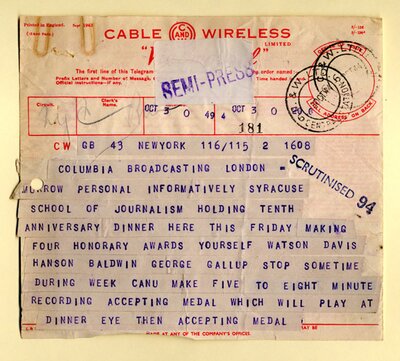

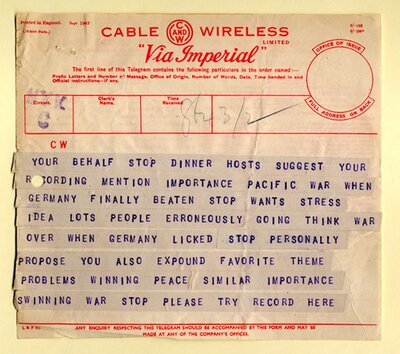

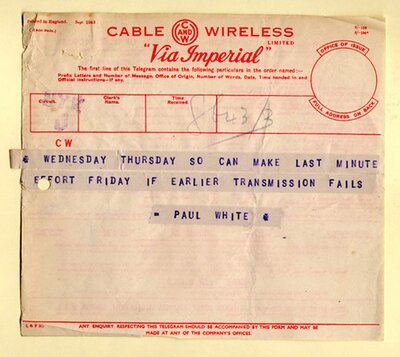

The work was dangerous as were the conditions under which it had to be done. Like other correspondents, Murrow's Boys barely managed to slip out of countries they had covered. They were thrown out by fascist regimes, were imprisoned, and lost family members (Lea Schiavi, a journalist and wife of Winston Burdett, was assassinated). They took part in bomb and reconnaissance flights, accompanied the Allied forces at innumerous fronts, participated in the invasion of Normandy, squabbled among and competed with each other, and still made up a memorable team of war correspondents. Murrow was well aware of this. He praised them liberally and ascribed his contribution to the field of journalism to their outstanding work; see here for example his acceptance speech for the Syracuse School of Journalism Award for Distinctive Achievements in News Analysis in late 1944.

Murrow did not interfere and seldom instructed the Murrow Boys on how to be a correspondent beyond the very general: to give the human side of the war, to be neutral and honest, to talk like him or herself, or to pitch the voice low. And herein lies Murrow's achievement: in having brought together this group of foreign correspondents and letting them do their work where they were at their best. Murrow's broadcasts were not necessarily better than theirs. Some wrote better. Some of Murrow's Boys had more subject knowledge and offered more trenchant analysis. They often worked under more dangerous and inconvenient conditions. They spoke the local languages. But in London, Murrow was centrally located, he was their boss, and he was a good coordinator. He elicited their good will and loyalty and gave both of these himself. He was very well-connected and his extensive speech training translated into a terse style and an excellent radio voice. Murrow knew how to use publicity, how to make himself look the role, and backed by CBS's efficient publicity machine, he thus became the iconic European news correspondent of World War II.

The Murrow Boys after the War

Reporting about World War II made Murrow's crew famous. After the war, Murrow would do much to help and support his 'Boys.' During his short stint as CBS Vice-President for News and Public Affairs, 1946-1947, he arranged top positions for those Murrow Boys still with CBS at the end of the war. This included Winston Burdett, Charles Collingwood, Bill Downs, Richard C. Hottelet, Larry LeSueur, Eric Sevareid, and Howard K. Smith. William L. Shirer had already returned in 1941 to work for CBS in the U.S. Many of the Murrow Boys would come together at least once a year in the 1950s to present the Years of Crisis television news round up consisting of in-depth analysis and commentary under the auspices of Murrow himself, and if necessary supplemented by other correspondents. A number of them wrote books about their war year reporting and experiences and became as influential as Murrow in the new medium of television.

1) The eleven Murrow Boys were identified by Janet Brewster Murrow during her interviews with Stanley Cloud and Lynne Olson, authors of 'The Murrow Boys.' (1996) The origin of the term is unknown but is in use by the late 1940s.

2) Mary Marvin Breckinridge Patterson, "Radio Scripts by Mary Marvin Breckinridge 1939-1940 for the World News Roundup Programs of the Columbia Broadcasting System and 'Talk to Professor Higgins' Graduate Class: Broadcasting from Europe to America 1939-1940" at the School of Journalism of Boston University, Wednesday, December 1, 1976; The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, DCA.

Credits

Text and Selection of Illustration

Susanne Belovari, PhD, M.S., M.A., Archivist for Reference and Collections, DCA

Digitization

Michelle Romero, M.A., Murrow Digitization Project Archivist

Images

All images: Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, TARC, Tufts University, used with permission of copyright holder, and Joseph E. Persico Papers, DCA.

Partial Bibliography

For a full bibliography please see the exhibit bibliography section.

All documents from The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, TARC, including:

Breckinridge Patterson, Mary Marvin, Radio Scripts by Mary Marvin Breckinridge 1939-1940 for the World News Roundup Programs of the Columbia Broadcasting System and 'Talk to Professor Higgins' Graduate Class: Broadcasting from Europe to America 1939-1940 at the School of Journalism of Boston University, Wednesday, December 1, 1976. January 15, 1940 Radio Broadcast number 9, 'Ice in Holland;' broadcast number 16, February 8, 1940, from Berlin, 'German Newspapers.'

Books consulted include Cloud and Olson (1996) in particular; also Persico (1988), Sperber (1986), and Kendrick (1969).

For Breckinridge, see also: Women Come to the Front: Journalists, Photographers, and Broadcasters During World War II, Library of Congress online exhibit, http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/wcf/wcf0009.html

Briggs (all volumes).

Miall, Leonard, 'Obituary: Helen Kirkpatrick Milbank,' The Independent, January 8, 1998

The Helen Paull Kirkpatrick Papers are at the Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, MA, see http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/sophiasmith/mnsss36_bioghist.html

Murrow, Edward R., Transatlantic Broadcasting, BBC Year Book, 1st proof, stamped December 10, 1942, in The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, TARC; eventually published in BBC Year Book 1943 (Jarrold & Sons, Ltd., Norwich & London), Transatlantic Broadcasting, by Edward R. Murrow, p. 82-86.

Sevareid, Eric, Not So Wild a Dream (1946), p. 493-495. First edition in The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, including a dedication by Eric Sevareid: " For Ed, In memory of many things, Eric."

Shirer, William L., Berlin Diary: The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent 1934-1941 (Alfred A. Knopf: New York 1940), p288, in The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, DCA.

"William L. Shirer, 1904-1993," We Bring History to Life, http://www.traces.org/williamshirer.html