Biography of Edward R. Murrow

Life apart from Work

In what he labeled his 'Outline Script Murrow's Carrer', Edward R. Murrow jotted down what had become a favorite telling of his from his childhood.

Edward R. Murrow, born near Greensboro, North Carolina, April 25, 1908. The third of three sons born to Mr. and Mrs. S. C. Murrow, farmers. About 40 acres of poor cotton land, water melons and tobacco. Earliest memories trapping rabbits, eating water melons and listening to maternal grandfather telling long and intricate stories of the war between the States. This experience may have stimulated early and continuing interest in history.

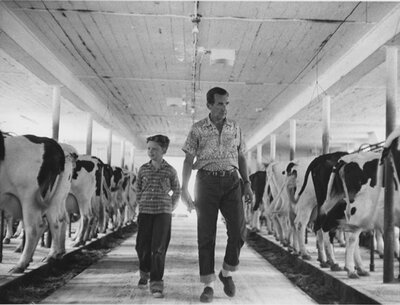

Family moved to the State of Washington when I was aged approximately six, the move dictated by considerations of my mother’s health. …Family lived in a tent mostly surrounded by water, on a farm south of Bellingham, Washington. My father was an agricultural laborer, subsequently brakeman on local logging railroad, and finally a locomotive engineer. The tree boys attended the local two-room school, worked on adjoining farms during the summer, hoeing corn, weeding beets, mowing lawns, etc. My first economic venture was at about the age of nine, buying three small pigs, carrying feed to them for many months, and finally selling them.The net profit from this operation being approximately six dollars. In later years, learned to handle horses and tractors and tractors [sic]; was only a fair student, having particular difficulty with spelling and arithmetic.

Beginning at the age of fourteen, spent summers in High Lead logging camp as whistle punk, woodcutter, and later donkey engine fireman. Became better than average wing shot, duck and pheasant,primarily because shells cost money. Last two years in High School, drove Ford Model T. school bus (no self-starter, no anti-freeze) about thirty miles per day, including eleven unguarded grade crossings, which troubled my mother considerably. Only accident was the running over of one dog, which troubled me….¹

Born in Polecat Creek, Greensboro, N. C., to Ethel Lamb Murrow and Roscoe C. Murrow, Edward Roscoe Murrow descended from a Cherokee ancestor and Quaker missionary on his father’s side. His mother, a former Methodist, converted to strict Quakerism upon marriage. Ethel Lamb Murrow brought up her three surviving sons strictly and religiously, instilled a deep sense of discipline in them, and it was she who was responsible for keeping them from starving particularly after their move out west. From an early age on, Edward was a good listener, synthesizer of information, and story-teller but he was not necessarily a good student. His name had originally been Egbert -- called 'Egg' by his two brothers, Lacey and Dewey -- until he changed it to ‘Edward’ in his twenties. Edward R. Murrow’s oldest brother, Lacey, became a consulting engineer and brigadier general in the Air Force Reserve. An alcoholic and heavy smoker who had one lung removed due to lung cancer in the 1950s, Lacey committed suicide in 1966. Murrow’s second brother, Dewey, worked as a contractor in Spokane, WA, and was considered the calm and down to earth one of the brothers.

Understandably and to his credit, Murrow never forgot these early years in the Southern and Western United States and his family’s background as workers and farmers. Throughout, he stayed sympathetic to the problems of the working class and the poor. Characteristic of this were his early sympathies for the Wobblies (Industrial Workers of the World) 1920s, although it remains unclear whether Edward R. Murrow ever joined the IWW. By the time Murrow wrote the 1953 career script, he had arguably become the most renowned US broadcaster and had just earned over $210,000 in salary and lucrative sponsoring contracts in 1952. This was twice the salary of CBS's president for that same year.² In the script, though, he emphasizes what remained important throughout his life -- farming, logging and hunting, his mother’s care and influence, and an almost romantic view of their lack of money and his own early economic astuteness.

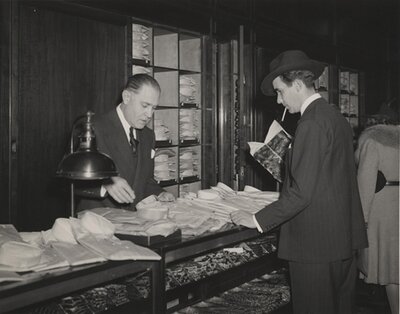

Of course, the official career script does not mention other aspects important in his life. Murrow had always preferred male camaraderie and conversations, he was rather reticent, he had striven to get an education, good clothes and looks were important to him as was obtaining useful connections which he began to actively acquire early on in his college years. He was, for instance, deeply impressed with his wife’s ancestry going back to the Mayflower. Edward R. Murrow and Janet Brewster Murrow believed in contributing to society at large. Both assisted friends when they could and both, particularly Janet, volunteered or were active in numerous organizations over the years. In 1954, Murrow set up the Edward R. Murrow Foundation which contributed a total of about $152,000 to educational organizations, including the Institute of International Education, hospitals, settlement houses, churches, and eventually public broadcasting. Janet Brewster Murrow usually decided on donations and James M. Seward, eventually vice president at CBS, kept the books until the Foundation was disbanded in November 1981.³

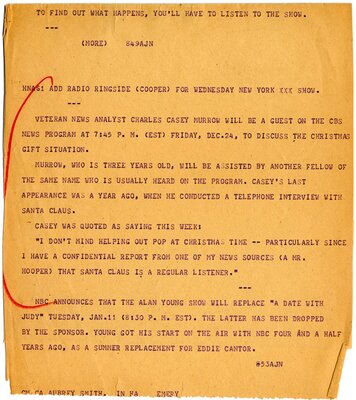

Just as she handled all details of their lives, Janet Brewster, kept her in-laws informed of all events, Murrow's work, and later on about their son, Casey, born in 1945. Murrow himself rarely wrote letters. He even stopped keeping a diary after his London office had been bombed and his diaries had been destroyed several times during World War II. One of Janet's letters in the summer of 1940 tells Murrow's parents of her recent alien registration in the UK, for instance, and gives us an intimation of the couple's relationship: "Did I tell you that I am now classed as an alien? I have to be in the house at midnight. I can't drive a car, ride a bicycle, or even a horse, I suppose. If I want to go away over night I have to ask the permission of the police and the report to the police in the district to which I go. Ed has a special exemption so that he can be out when he has to for his broadcasts. He could get one for me too, but he says he likes to make sure that I'm in the house - and not out gallivanting!"⁴

Janet and Edward were quickly persuaded to raise their son away from the limelight once they had observed the publicity surrounding their son after Casey had done a few radio announcements as a small child. Consequently, Casey remained rather unaware of and cushioned from his father's prominence. In the late 1940s, the Murrows bought a gentleman farm in Pawling, New York, a select, conservative, and moneyed community on Quaker Hill, where they spent many a weekend. For Murrow, the farm was at one and the same time a memory of his childhood and a symbol of his success. It's where he was able to relax, he liked to inspect it, show it off to friends and colleagues, go hunting or golfing, or teach Casey how to shoot. Not surprisingly, it was to Pawling that Murrow insisted to be brought a few days before his death.

Throughout the years, Murrow quickly made career moving from being president of NSFA (1930-1932) and then assistant director of IIE (1932-1935) to CBS (1935), from being CBS's most renown World War II broadcaster to his national preeminence in CBS radio and television news and celebrity programs (Person to Person, This I Believe) in the United States after 1946, and his final position as director of USIA (1961-1964).

... A More than Private Person ...

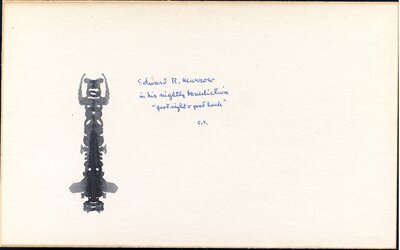

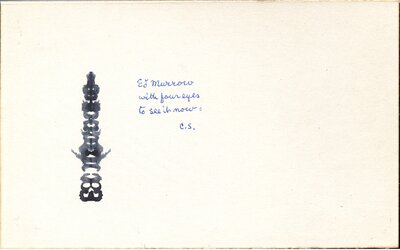

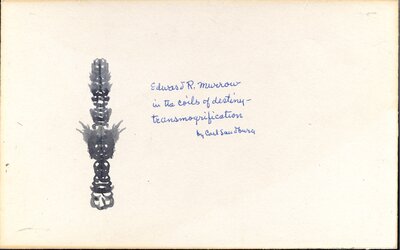

While Murrow remained largely withdrawn and became increasingly isolated at CBS after World War II -- which is not surprising given his generally reticent personality, his stature, his workload, and his increasingly weakened position at CBS -- many of his early colleagues from the war, the original 'Murrow Boys', stayed as close as he would let anyone get to him. This war related camaraderie also extended to some of the individuals he had interviewed and befriended since then, among them Carl Sandburg. The following story about Murrow's sense of humor also epitomizes the type of relationship he valued:

"In the 1950s, when Carl Sandburg came to New York, he often dropped around to see Murrow at CBS. One afternoon, when I went into Murrow's office with a message, I found Murrow and Sandburg drinking from a Mason jar - the kind with a screw top - exchanging stories. It was moonshine whiskey that Sandburg, who was then living among the mountains of western North Carolina, had somehow come by, and Murrow, grinning, invited me to take a nip. It was almost impossible to drink without the mouth of the jar grazing your nose. That, Murrow said, explained the calluses found on the ridges of the noses of most mountain folk."⁵

Understandable, some aspects of Edward R. Murrow’s life were less publicly known: his early bouts of moodiness or depression which were to accompany him all his life; his predilection for drinking which he learnt to curtail under Professor Anderson's influence; and the girl friends he had throughout his marriage. The most famous and most serious of these relationships was apparently with Pamela Digby Churchill (1920-1997) during World War II, when she was married to Winston Churchill's son, Randolph. Although she had already obtained a divorce, Murrow ended their relationship shortly after his son was born in fall of 1945.

Tributes

Murrow’s last broadcast was for "Farewell to Studio Nine," a CBS Radio tribute to the historic broadcast facility closing in 1964. And it is a fitting tribute to the significant role which technology and infrastructure had played in making all early radio and television programs possible, including Murrow's. In the program which aired July 25, 1964 as well as on the accompanying LP record, radio commentators and broadcasters such as William Shirer, Eric Sevareid, Robert Trout, John Daly, Robert Pierpoint, H.V. Kaltenborn, and Edward R. Murrow listened to some of their old broadcasts and commented on them. With Murrow already seriously ill, his part was recorded at the Lowell Thomas Studio in Pawling in spring of 1964.⁶

Of course, there were numerous tributes to Edward R. Murrow as the correspondent and broadcaster of famous radio and television programs all through his life. Awards, recognitions, and fan mail even continued to arrive in the years between his resignation due to cancer from USIA in January 1964 and his death on April 15th, 1965. Murrow's influence on news and popular culture in the United States, such as it was, can be seen in letters which listeners, viewers, or individuals whose cause he had taken up had written to Murrow and his family. Just shortly before he died, Carol Buffee congratulated Edward R. Murrow on having been appointed honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire, adding, as she wrote, a small tribute of her own in which she described his influence on her understanding of global affairs and on her career choices.

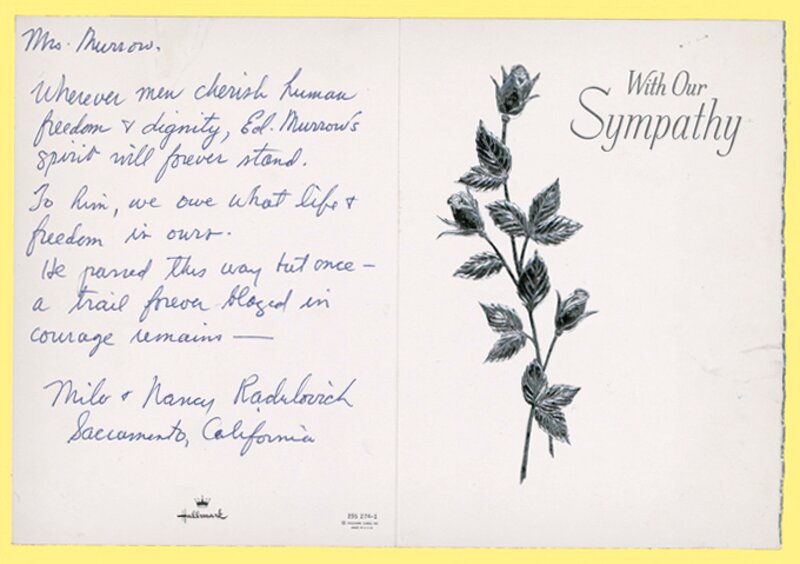

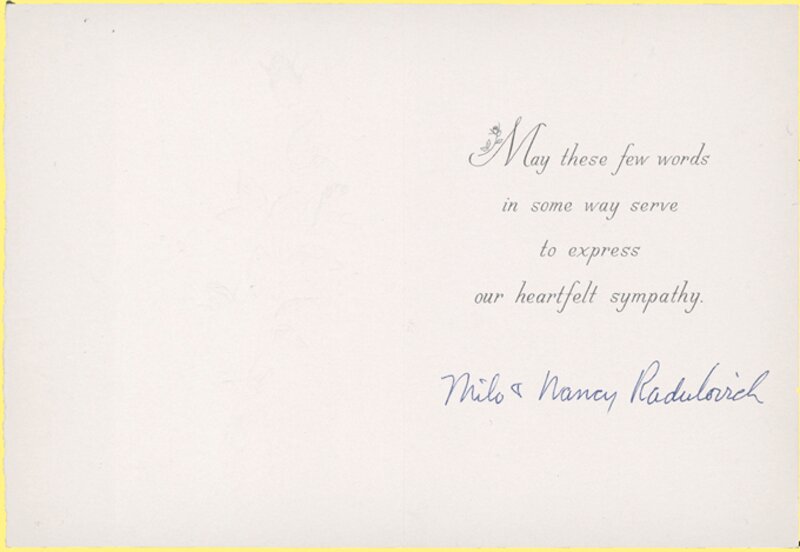

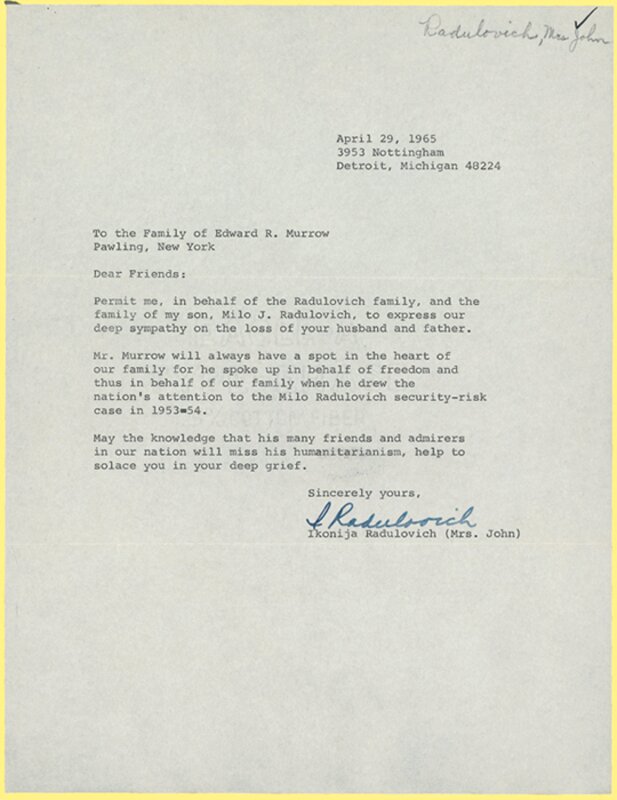

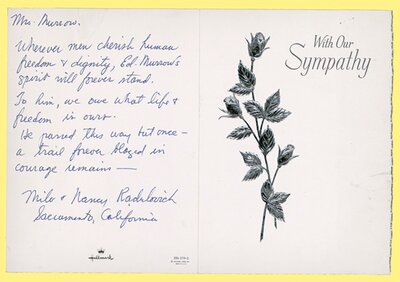

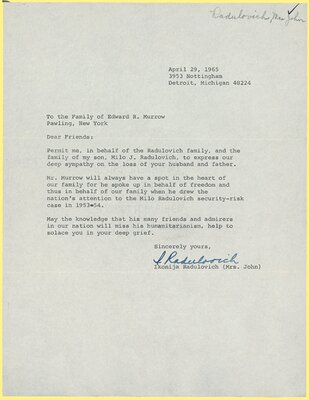

Upon Murrow’s death, Milo Radulovich and his family sent a condolence card and letter. In it, they recalled Murrow's See it Now broadcast that had helped reinstate Radulovich who had been originally dismissed from the Air Force for alleged Communist ties of family members. Offering solace to Janet Murrow, the Radulovich family reaffirmed that Murrow's humanitarianism would be sorely missed.⁷

... something akin to a personal credo ...

By bringing up his family's poverty and the significance of enduring principals throughout the years, Murrow might have been trying to allay his qualms of moving too far away from what he considered the moral compass of his life best represented perhaps in his work for the Emergency Committee and for radio during World War II and qualms of being too far removed in life style from that of 'everyday' people whom he viewed as core to his reporting, as core to any good news reporting, and as core to democracy overall. A letter he wrote to his parents around 1944 reiterates this underlying preoccupation at a time when he and other war correspondents were challenged to the utmost physically and intellectually and at a time when Murrow had already amassed considerable fame and wealth - in contrast to most other war correspondents.

“Every time I come home it is borne in upon me again just how much we three boys owe to our home and our parents. Probably much of the time we are not worthy of all the sacrifices you have made for us. We have all been more than lucky. When things go well you are a great guy and many friends. You can make decisions off the top of your head and they seem always to turn out right. It is only when the tough times come that training and character come to the top.It could be that Lacey (Murrow) is right, that one of your boys might have to sell pencils on the street corner. But that is not the really important thing. How much worse it would be if the fear of selling those pencils caused us to trade our integrity for security. For my part, I should insist only that the pencils be worth the price charged. No one knows what the future holds for us or for this country, but there are certain eternal verities to which honest men can cling. Most of them you taught us when we were kids. The more I see of the world’s great, the more convinced I am that you gave us the basic equipment—something that is as good in a palace as in a foxhole.

Take good care of your dear selves and let me know if there are any errands I can run for you." ⁸

1) The Outline Script Murrow's Career is dated December 18, 1953 and was probably written in preparation of expected McCarthy attacks.

2) See here for instance Charles Wertenbaker's letter to Edward R. Murrow, November 19, 1953, in preparation for Wertenbaker's article on Murrow in the December 26, 1953 issue of The New Yorker, Edward R. Murrow Papers.

3) Letter by Jame M. Seward to Joseph E. Persico, August 5th 1984, in folder labeled 'Seward, Jim', Joseph E. Persico Papers, TARC.

5) Letter from Edward Bliss Jr. to Joseph E. Persico, September 21, 1984, folder 'Bliss, Ed', Joseph E. Persico Papers, TARC.

6) Friendly Farewell to Studio 9: letter by Fred W. Friendly to Joseph E. Persico, May 21, 1985, Friendly folder, Joseph E. Persico Papers, TARC. See also: http://www.authentichistory.com/ww2/news/194112071431CBSTheWorld_Today.html which documents a number of historical recreations/falsifications in these re-broadcasts (accessed online November 9, 2008).

7) Edward R. Murorw received so much correpondence from viewers and listeners at CBS -- much of it laudatory, some of it critical and some of it 'off the wall' -- that CBS routinely weeded these letters in the 1950s. While public correspondence is part of the Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, at TARC, it is unknown what CBS additionally discarded before sending the material to Murrow's family. The surviving correspondence is thus not a representative sample of viewer/listener opinions.

8) Excerpt of letter by Edward R. Murrow to his mother, cited on p. 23 of the 25 page speech titled ‘Those Murrow Boys,’ (ca.1944) organized by the General Aid Program Committee – the original letter is not part of the Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, TARC, Tufts University.

Credits

Text and Selection of Illustration

Susanne Belovari, PhD, M.S., M.A., Archivist for Reference and Collections, DCA (now TARC)

Digitization

Michelle Romero, M.A., Murrow Digitization Project Archivist

Images

All images: Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, DCA, Tufts University, used with permission of copyright holder, and Joseph E. Persico Papers, TARC.

Partial Bibliography

For a full bibliography please see the exhibit bibliography section.

The Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985, also Joseph E. Persico Papers and Edward Bliss Jr. Papers, all at TARC. Books consulted include particularly Sperber (1986) and Persico (1988).

Charles Wertenbaker's letter to Edward R. Murrow, November 19, 1953, in preparation for Wertenbaker's article on Murrow for the December 26, 1953 issue of The New Yorker, in Edward R. Murrow Papers, ca 1913-1985.