Chair in the Field

From Writing Poetry (Boston: The Writer, Inc., 1960) 39-42

One summer we stayed in another house in a different part of Vermont. One August noon our ten-year-old son urged us to have the necessary mid-day meal out in the tree-ringed field in front of the old house. We did, and all three stayed there for a nap afterward. It was getting dark that night, and I was rounding up child, tools, car, toys, clothes, and all the things one learns to take care of in the country, when I saw from the front porch one of the blue chairs from the dining-room still out there in the field, incongruous, annoying, and somehow touching. But I felt again the urgency of my son's happy plan for that field picnic, a plan unexpectedly come from him when unknown to him it was desperately needed. I walked out through the grass, fetched the chair in, and still felt I wanted to save the particularity of the incident, his small stay made against the passing of life.

Here is an approximate reproduction of the seven worksheets I needed to write that poem. Here again, as I think back, was the same pull: anger and affection, and a need to clear my own feelings. The image seen was the one that meant most, and what I called the poem:

At half past six in August, two trees had begun to yellow

To bronze, two bordering our mowed field.

It was toward evening and September, growing cold.

A blue chair stood in the grass.

Crossings-out and fussings-about, and second, fifth, and seventh tries to get away to a clean fast start eventually changed these opening four lines to this final version:

At half past six in August, two trees,

Yellowing to bronze, bordered our mowed field.

It was toward evening and September, growing cold.

A blue chair stood in the grass.

The change here, which no one should be as slow as I am to make, is simply in the condensation of verb forms. "Had begun to yellow to bronze" is notebook stuff, first jottings. "Two" is unnecessarily repeated. "Bordering" is a weaker form than "bordered." And I was in a hurry to get on, to say:

This is what it was.

Wishing I do not know what rush of joy among us,

The boy child in the old summer farm house

At noon had us to the meadow with steak and corn,

Cloud mapping the blue as after

We three sprawled on blankets of sun

And almost slept.

I was in a hurry, and that was what I wanted to say, but there was fumbling, and wordiness, and clumsiness in line-division. At first I didn't get "at noon" in at all, for its sound and rhythm, and for the very necessary time-plot of the poem. The whole point had to be that I looked out the door at dusk, and then went back in my mind and emotions to explain and, as it happened, to rejoice in the chair out there. But one of the last touches was "blankets of sun" instead of the dull, literal first version, "blankets." I'd known enough to say "and almost slept," because that is what it was-we drowsed, murmured now and then, and the sun was hot, and the countryside quiet and vastly empty. But the heat, the pouring light, the sense of a skyful of it, and all for us!

But I still had to bring the time-scheme up to the point of the first "inspiration," that badly worn word. I had wanted to say, simply, "Johnny, darn you, I thought I told you to bring everything in, and you've gone and left one of the dining-room chairs out. How many times have I told you that the dew spoils our tools and baseball gloves and everything, if we don't bring them in?" But I was grinning to myself, out there on the porch. The lunch in the meadow had been his idea, wholly, for some deep need of family togetherness, and he had tirelessly carried the food and dishes to make it be. How could I be angry, or even mildly exasperated? No. It was an image, that blue chair in the field, that meant a great deal.

He later and we brought back to the house

The table, the milk, the spoons, the lucky idea.

Looking out after sunset I saw it,

The one chair blue there in green grass,

Human and his.

Time was ours and time goes

In shine and hurry as a boy grows.

I was for leaving it there to remember the day by.

That's the way the poem ends, in the version which was published in the Atlantic for August, 1947. By the time I put it into a book, The Double Root, 1950, I was dubious about the easy, redundant last lines. The whole feeling I had in that moment on the cool, darkening farmhouse porch, of a minor annoyance quickly turning into love, is in "Human and his," and "I was for leaving it there -." And I would have. I thought, I'll leave it out there, and not scold him. I'll tell him it reminds me of the good time we had yesterday. And he would look at me, a little puzzled, and maybe think I was trying to "teach him a lesson" in the often laborious and mysterious way grown-up people do. So I brought it in. And wrote the poem. But in the book the last lines are:

This is the way the world runs down.

But I was for leaving it out

To remember the day by.

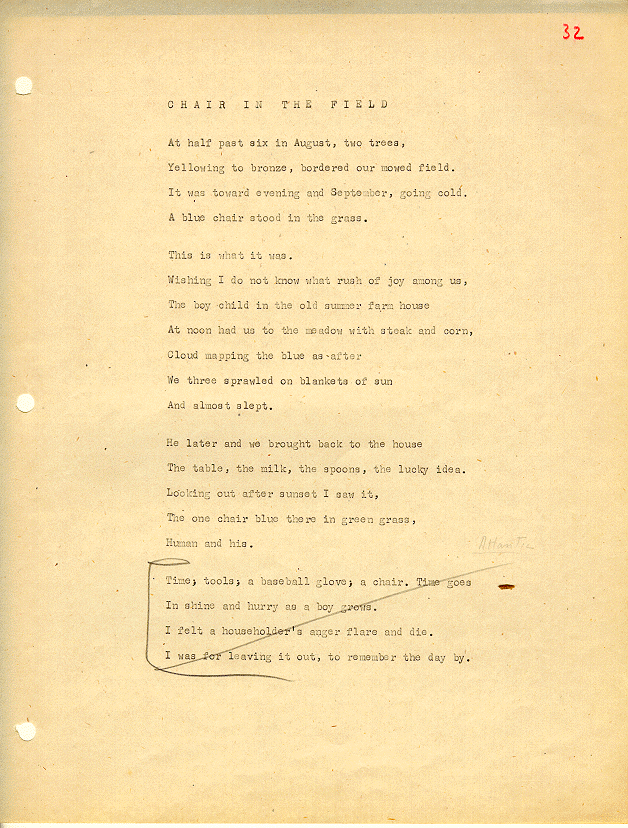

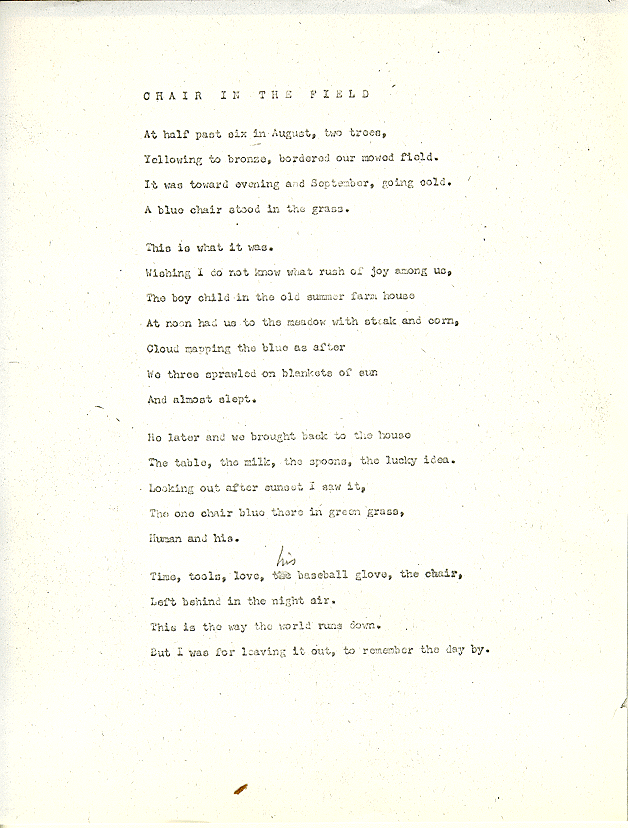

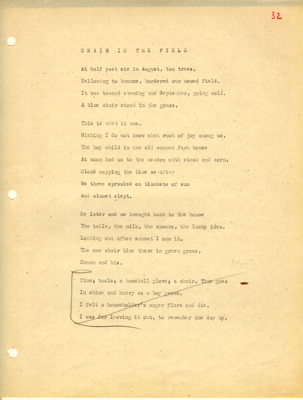

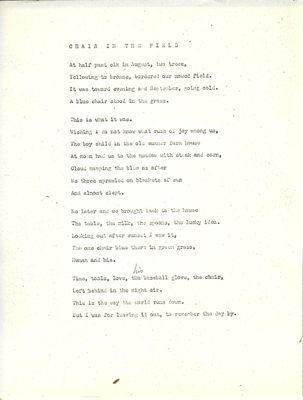

The two manuscript copies of the poem in the John Holmes Collection show alternate versions of the last stanza, different from the two mentioned by Holmes in the essay above. The first three stanzas of the poem are in the final form of the published version.

Though neither manuscript page is dated, the pages are placed in the order in which they might have been written.

Listen to "Chair in the Field" read aloud.